From our archives: Rules to limit suffering

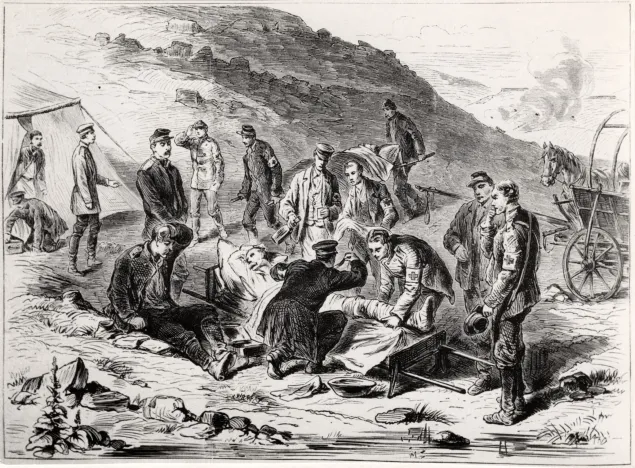

Ottoman Empire, Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78. First-aid post for wounded soldiers. The 1864 Geneva Convention stipulated that wounded soldiers and those coming to their aid must not be targeted; they must be spared and protected.

1925: Banning chemical weapons

Ypres, Belgium, 1917. Australian soldiers wear masks to protect themselves from poison gas. Chemical weapons were widely used during the First World War, causing death or terrible injuries. The 1925 Geneva Protocol prohibited the use of asphyxiating and poisonous gases in war.

1929: Protecting prisoners of war

Roche-Maurice, France, First World War. German prisoners of war have a meal in their camp dormitory. The 1929 Convention on prisoners of war was expanded and strengthened in 1949 by the Third Geneva Convention.

1948: Preventing genocide

Poland, Second World War. A dormitory in a concentration camp. The Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was unanimously adopted in 1948 by the United Nations General Assembly, founded three years previously.

1949: Protecting the shipwrecked

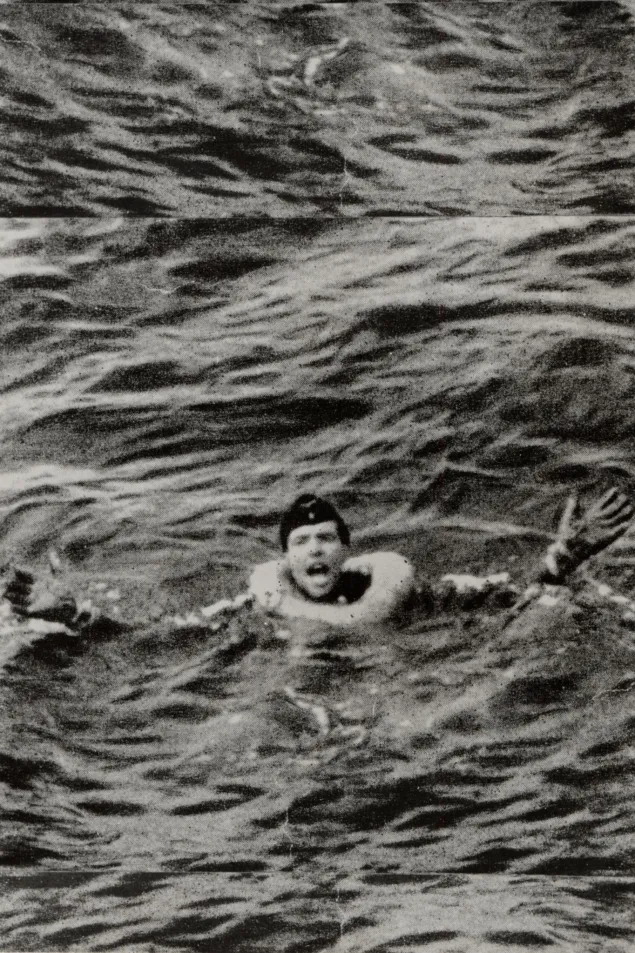

A shipwrecked British pilot calls for help, Second World War. The Second Geneva Convention extended protection to the wounded, sick and shipwrecked members of armed forces at sea. The four Geneva Conventions of 1949 – now universally ratified – and their Additional Protocols are the backbone of international humanitarian law.

1949: Protecting civilians

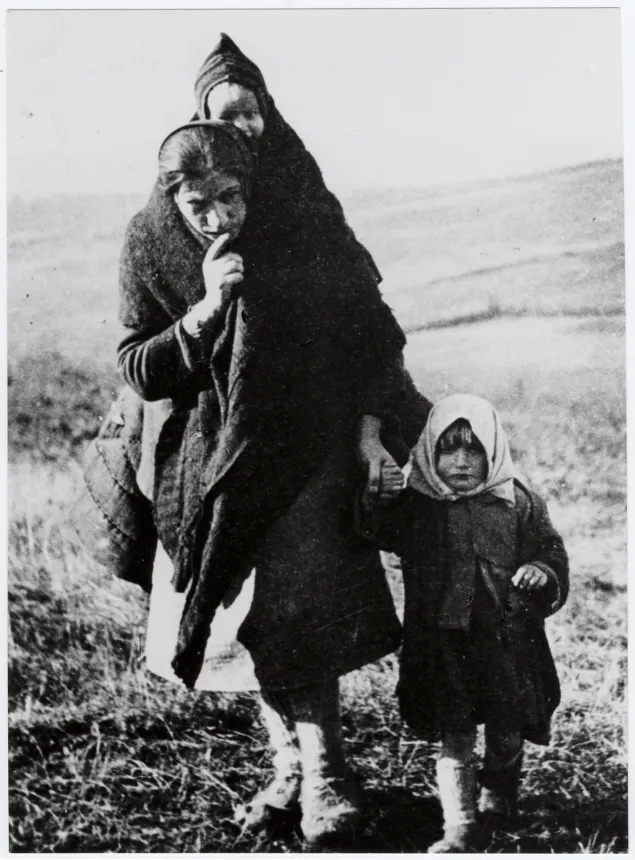

Refugees from Kozara, Yugoslavia (now Bosnia and Herzegovina), Second World War. The treaties adopted prior to 1949 only enshrined protection for combatants no longer taking part in the hostilities. The terrible suffering endured by civilians during the Second World War brought to the fore the need to protect civilians, especially in occupied territory, and resulted in the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949.

1954: Protecting cultural property

Dresden, Germany, after the bombing of February 1945. The massive bombing attacks during the Second World War raised the issue of protecting works of art and other cultural heritage in conflict. The 1954 Hague Convention and its Protocol prohibited the targeting of cultural property and obliged the parties to conflict to refrain from damaging such property.

1977: Protecting victims of civil war

Rorazau, El Salvador, 1980. A Salvadorean Red Cross convoy prepares to distribute relief to people driven from their homes by the conflict between the government and the Farabundo Marti National Liberation Front. Most of the rules of international humanitarian law protected the victims of armed conflict between States. The two Additional Protocols of 1977 extended that protection to victims of internal conflicts and wars of national liberation.

1989: Protecting children

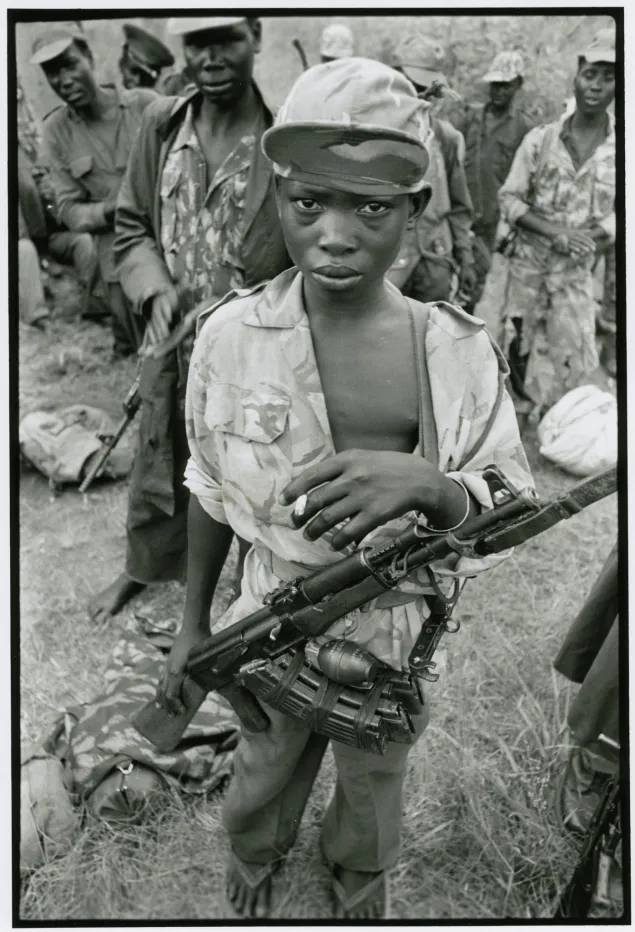

Between Kampala and Luwero, Uganda, 1986. A 12-year-old child soldier for the National Resistance Army. The Convention on the Rights of the Child, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1989, enshrines the fundamental rights of children. Article 38 protects them in the event of an armed conflict by prohibiting the recruitment into armed forces of children under the age of 15. The 2000 Protocol to the Convention supplements this by stipulating that armed groups should not, under any circumstances, recruit children under the age of 18.

1997: Banning anti-personnel mines

Battambang, Cambodia. Khan Keo, aged 10, stepped on a mine as he was crossing a paddy field with his cows. Thon Thau, 14, stepped on one while gathering wood. Anti-personnel mines do not distinguish between civilians and fighters. They continue to kill and maim long after the fighting has ended. The 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention prohibits the use, stockpiling, production and transfer of these devices.

1998: Punishing war criminals

Potočari, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2001. Commemoration of the sixth anniversary of the fall of Srebrenica, which was followed by the massacre of thousands of Bosniaks. The Rome Statute of 1998 established the International Criminal Court to try alleged perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity and acts of genocide when individual countries are not able or willing to bring them to justice.

2008: Banning cluster munitions

Rashidieh refugee camp for Palestinians near Tyre, southern Lebanon, 2007. A young victim of a cluster bomb. The 2008 Convention banned the production and use of cluster munitions, which are particularly dangerous for civilians: they scatter explosive devices over a large area and often do not explode immediately.

2013: Regulating the arms trade

Muzbat, Sudan, 2006. Fighters from the Sudanese Liberation Army. The unregulated trade in, and abuse of, arms has tragic humanitarian consequences. The 2013 Arms Trade Treaty aims to protect civilians by regulating the transfer of conventional weapons.

Even war has limits. The rules established by international humanitarian law protect those who are not, or no longer, participating in the hostilities – namely civilians and wounded, sick or captured fighters – and restrict the means and methods of warfare. All those taking part in the fighting have a duty to distinguish between combatants and civilians and must not target civilians. But signing treaties is not enough; all too frequent violations of humanitarian law in conflict have an unacceptable human cost. Today, more than ever, we call upon all parties to conflict to spare civilians and respect international humanitarian law.