Nigeria: “Life will never be as it used to be before”

The only businesses open in the village of Gulak are a barber and a tailor. On the ground outside, two men sort through a pile of peanuts, two young girls walk between checkpoints manned by local vigilantes.

But the quiet does not signify peace. Far from it.

"There have been five attacks in the last month," says Usman Ali, the chairman of the Vigilante Group of Nigeria, a local militia that offer support to the government soldiers.

Gulak is located in the north east of Adamawa state, an area blighted by fighting and conflict between the government and a heavily armed insurgent group. They seized control of the village in September, 2014, but were forced out by government soldiers and local militias in March last year.

Two young girls walk between two checkpoints in the village of Gulak, in the north east of Adamawa state, a region rocked by violence and instability over the past few years. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / William Davies

Over 2 million people were forced from their homes in the Lake Chad region at the height of the conflict that has blighted this region since 2009. In Borno and Adamawa state in Nigeria, most headed south, to camps set up for displaced people, or across the border to Cameroon.

As the armed opposition has lost ground, people have been able to return home, but many have found rubble where their homes once stood.

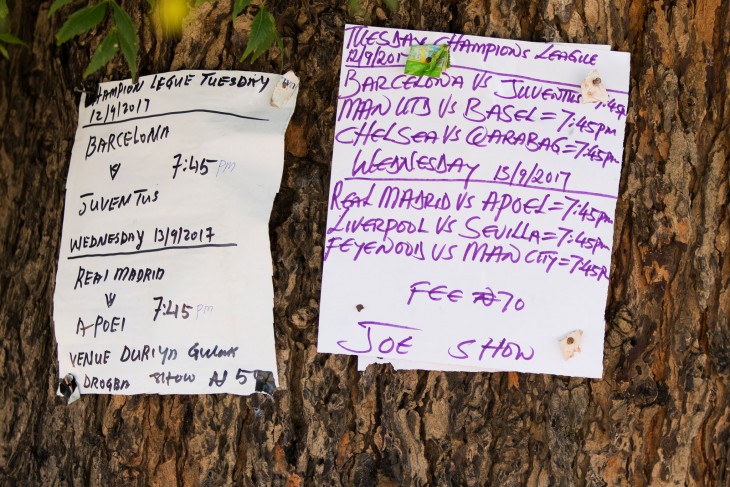

Travel a few kilometers south from Gulak, and you'll reach the town of Michika, with a thriving market, DVD shops, even posters advertising the next Champions League football match, something unthinkable when it was being controlled by the armed opposition. But behind the main road the scars of the fighting are everywhere. Houses in ruins, bullet holes dot the walls that remain and bomb craters the size of cars litter the ground.

Posters advertising upcoming champions league matches are common in towns and villages in Adamawa state, something unthinkable when the armed opposition controlled this area. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / William Davies

"When I came back I didn't find anything, none of my belongings were still here, my house was destroyed," says 44 year old Ladi Abdul, who spent three years living in a camp. "I've been back in my town for around three months now, after peace was restored in my community."

"Throughout this whole crisis we have suffered a lot," she says. "I still don't have any business, I don't have anything to do. I have children and I'm a single mother."

Ladi Abdul poses for a photo in her recently rebuilt house in Michika. Abdul's house was destroyed in fighting in 2014 and she spent three years living in a camp with her children. The ICRC helped rebuild her house and she moved in three months ago. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / William Davies

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is one of only a few aid agencies working in the area. They rebuilt Adbul's house, along with over 700 other properties. "I was not expecting to find myself here and have a roof over my head," she says. "Because of the Red Cross, I have a house of my own."

They've also distributed thousands of kilos of seeds and fertilisers, to help farmers get back on their feet after they missed several planting seasons. Food insecurity has been one of the biggest challenges in the region.

Two hours south of Michika is the town of Mubi, where a transit camp for displaced people is home to just 57 people, the majority of whom have recently escaped from the armed opposition.

But in the last years, thousands of people have passed through the camp, and more are expected.

A young fuel attendant sits outside an oil shop on the Michikia roadside. The town was taken over by the armed opposition forcing thousands of people to flee. But thousands have returned to their homes in recent months. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / William Davies

"We are expecting another 50,000 people from across the border in Cameroon," says Abubakar Fudamu, the head of the Nigerian Red Cross in Mubi.

And all of them will need help from aid agencies. "The host community is exhausted with the IDPs," Fudamu says ."They will not be able to help them."

The ICRC monitors the new arrivals at the transit camp. "We recently had someone who came with six children, who were all malnourished," says Dr Kennedy Yakubu, a field officer with the ICRC in Mubi. "We took them to the primary health care centre which the ICRC supports, where they received free health care."

There are speculations that the Adamawa state government might be closing the camps for the displaced persons by the end of the year, but many say they will have nowhere to go, and nothing to live on when they get there.

Malkohi camp on the outskirts of the town of Yola is home to 1,000 Nigerians, most of whom live in tents. Some though have spent the crisis living in an old school building, where bunk beds are crammed together offering little privacy.

Naomi Dauda has been living in the camp for three years and says she can't return to her home village as it is still unsafe. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / William Davies

Naomi Dauda sleeps on a bottom bunk, with her 14 month old son Habu and her husband. On the top bunk is a pile of knitting — Naomi's been trying to start a small business selling children's wollen hats.

"Our village was captured, so we had to flee," she says. "Everything was burnt to the ground." Naomi says her village still comes under attack, and she says it wouldn't be safe for her to return. She also has nothing to return back to, as her house has been destroyed. "I'm worried because we've heard that by December the camp will be shut, so I don't know what will happen."

"Life will never be as it was before," she says.