Afghanistan: Children are the main victims of unexploded and abandoned weapons

Seven-year-old Omar’s daily routine used to involve going with his brother and some friends to the fields near their home in Kabul’s Khake Jabar district and gathering fodder for their cattle. He knew the chore well and could quite easily find his way around those familiar fields. But everything changed for him on 4 May 2023.

Omar does not clearly remember what happened but there was an odd object in the field that had caught the boys' curiosity. Before they could figure out what it was, the object exploded, killing Omar's nine-year-old brother, and severely injuring the others. Omar lost his right leg and sustained deep wounds on his abdomen.

An ongoing threat

Unexploded and abandoned weapons are a very real and persisting threat to civilians returning to the homes and communities they had fled amid decades of fighting in Afghanistan. Though the fighting has decreased, people's lives continue to be disrupted because efforts to clear the landmines and other unexploded weapons have not been entirely successful. This has resulted in an increase in casualties since August of 2021. Children have been particularly vulnerable to fatal or life-changing injuries as they unintentionally step on landmines or pick up unexploded ordnance (UXO) littered around the places they stay, play or do household chores.

Highlighting the urgent need for additional efforts to address the issue of weapon contamination, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has recorded that 640 children were killed or injured in 541 incidents involving landmine explosions and explosive remnants between January 2022 and June 2023. This is nearly 60 per cent of the total number of civilian casualties (1,092 people) because of UXO related incidents.

Omar with his father at the ICRC's physical rehabilitation centre in Kabul city. Mohammad Masoud SAMIMI/ICRC

Living through trauma

"Children from our neighbourhood are usually assigned the chore of gathering fodder for our cattle from the nearby fields. On 4 May, when they went to the fields, they discovered a strange-looking metal object. They may have handled it or thrown it, causing an explosion," says Wakeel, Omar's father. He shares that they got news of the incident from the local authorities. "I had to first go and bury one of my sons and then rush to a hospital in Kabul to see my other son, whose body was covered with wounds," says Wakeel.

Sitting beside Omar, who has been very quiet since the traumatic incident, Wakeel says his son loved playing cricket and was recently enrolled in a primary school. "He aspired to be a doctor or an engineer one day. Though the incident has made life significantly more difficult for him, I'm confident that he will be able to achieve his goals after receiving an artificial limb. He needs help to persevere through the struggles that lie ahead," says Wakeel.

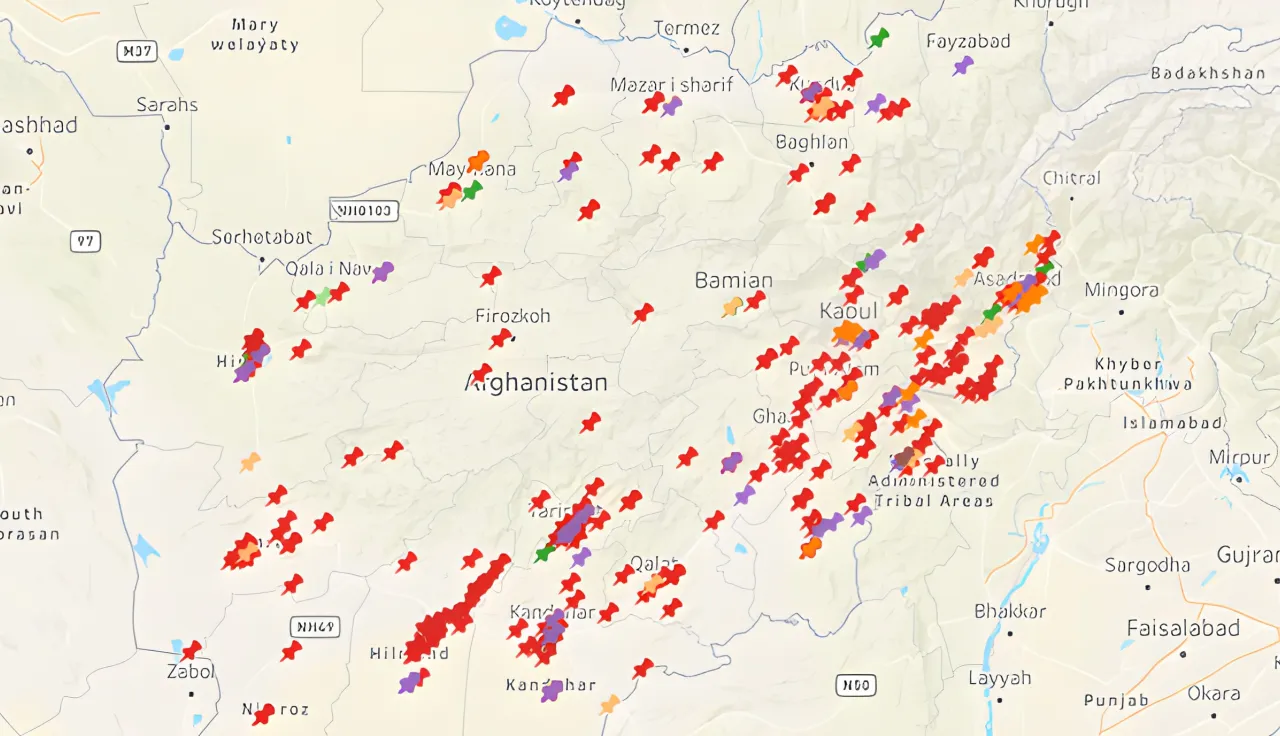

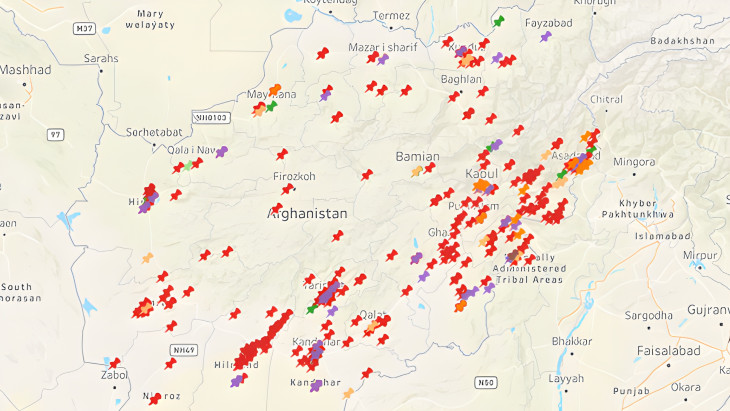

A map of Afghanistan showing the number and location of incidents related to landmine and UXO explosions between January 2022 and March 2023. GRAPHIC: ICRC

Mohammad Dauowd, a physiotherapist at the physical rehabilitation centre where Omar is being treated, can relate with the trauma that the child may be experiencing. Dauowd is one of the 90 per cent people with disabilities working for the ICRC's physical rehabilitation programme. Sharing his own journey from trauma to building resilience, Dauowd says, "Children who lose limbs because of explosions suffer deep trauma. In 1992, I was a 17-year-old playing football with my friends when a UXO exploded on the ground and I lost my leg. I suffered a lot psychologically following the incident and thought my life was over." But over the last few decades having helped people like himself walk again with prosthetics, he says, "Today I am happy that I am able to serve victims of landmines and unexploded ordnance."

Lack of awareness a major challenge

Mohammad Naser Haidari, an ordnance disposal expert with the ICRC, explains why civilians, particularly children, are the primary victims of landmine and unexploded ordnance related incidents. "Areas that were used as military bases or where armed conflicts took place over the last 40 years have been contaminated by abandoned or unexploded weapons. Now since the fighting has decreased significantly, those who had fled their homes during the armed conflict are returning and they are able to travel to areas that were previously inaccessible, exposing them to greater risk of coming across unexploded ordnance," he says.

Haidari adds that lack of knowledge about unrecognized explosive objects is a major challenge. "The ICRC has programmes to raise public awareness about the risks and dangers of landmines and unexploded ordnance. We run these independently as well as in partnership with the Afghan Red Crescent Society, by organizing training for volunteers, collecting data of incidents, distributing educational and informative materials and providing cash assistance to affected families to cover unforeseen expenses such as medical and funeral costs," he says.

ICRC Physiotherapist Supervisor at Kabul's physical rehabilitation centre. Mohammad Masoud SAMIMI/ICRC

Following the change in authorities in Afghanistan, many donor states and organizations withdrew their funding. The dramatic drop in resources and funding had an equally dramatic impact on efforts to clear landmines and unexploded ordnance. There is, however, still a desperate need for the international community to provide technical and financial assistance to reduce the number of human casualties caused by unexploded devices.