France: Capturing the humanity of Calais migrants

It’s a grey day, like any other. Those who want to call home have converged on the waste ground. The Red Cross team in charge of providing the family links service has organized the queue. Smiles and comforting words break through the mist. Everyone here will get their ten minutes of conversation.

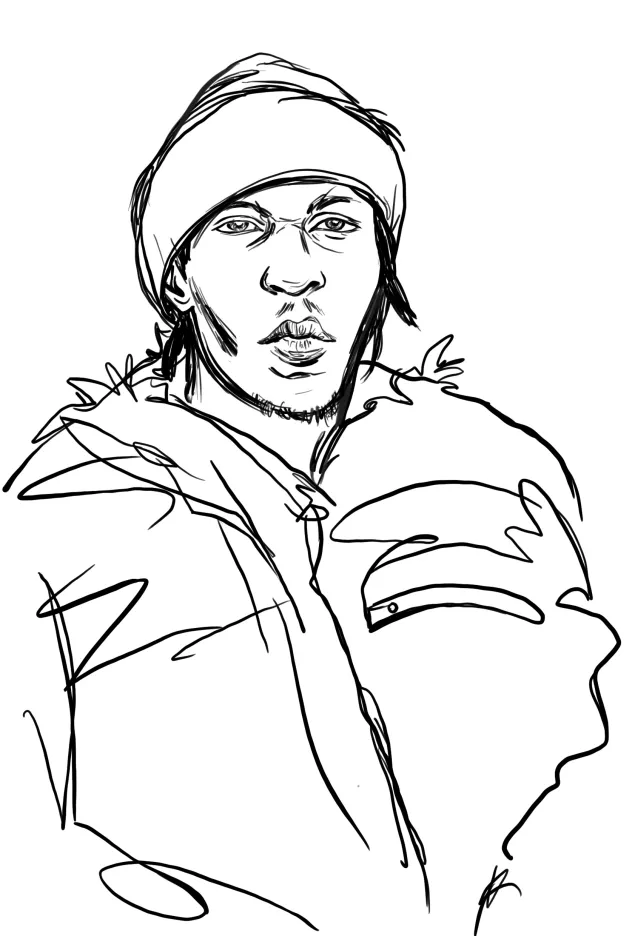

A quiet, solemn man stands in line. He lets himself be sketched, seeming indifferent. In a few quick strokes, his image and strain are captured on paper. He takes the drawing, glances at it and then hands it back, his face expressionless. He walks away but then turns and reconsiders the drawing. His face softens and he breaks into an unexpected smile.

I'm lost

“Paris is like the Tower of Babel. The people there speak every language under the sun, including mine, but no one even tried to understand me. I created a sign explaining my plight and I walked around with it, but nothing – no one read it. I wandered aimlessly and, after some time, I realized I was lost in a city that fears me as it fears the words on my sign.

At last, someone came and spoke to me in my own language: انت ضائع. You are lost.” He showed me where to go and that’s how I ended up here. Since then, I’ve been told time and again to go over there, to cross again, but always moving further away from where I came from.”

Is there a way out?

The day centre brings together several associations and the courtyard is buzzing with activity. This is where phones are charged and clothes are washed. People dodge the stray ball from an impromptu game of football. Red Cross volunteers and nurses pass by. A service to call family back home is also on offer. A young man is drawing the coloured concrete wall that surrounds the courtyard. He has drawn the top of the wall right along the edge of the paper, leaving the sky as an abstract notion – a bit like hope.

From cell to cell

Othman was forced to take up arms and, at the age of 16, he found himself in a tiny cell – death as his only way out. Against all odds, he managed to escape. He still cannot get his head around how his escape was even possible. Looking at him, you cannot imagine the full extent of the horrors he endured in order to survive hell.

Now, he is a different type of prisoner, a prisoner through exile. Emotional at the prospect of contacting his loved ones, he hesitates: “What am I going to say to my family?”

When you leave, a part of you dies.

Learning

Before being orphaned, Kamal’s childhood had been a happy one. His father had taught him how to sail in order to fish, which is how he ended up acting as unofficial captain of an overcrowded small boat crossing the Mediterranean. He reached land and continued his journey, moving from one country to another. Now, on the horizon, is the British coast. He speaks English and dreams of getting an education. He has been telling his story confidently. But then, the child who grew up too quickly suddenly asks: “What about you? What do you think? Should I attempt the crossing or not?”

The regular

Abdo is a familiar face at the day centre and the social care points. His story is heart-wrenching. He was the only survivor when his family’s apartment was destroyed by a bomb. He was lucky to be rescued and had no other choice but to flee the apocalypse his village had become. Despite all the people surrounding him, he remains wrapped in his own thoughts, his gaze hard, trapped in the aftermath of a war he does not understand.

The tent

Olan and Jorin share a tent among the trees, tarpaulins and general detritus of the false haven known as the “jungle”. They know the specialist Red Cross instructor well because whenever she’s on duty, she comes to check on them. Sleepy glances, snippets of conversation, laughter and teenage teasing. A blend of pop music and the explosions in their country at war reverberate from their phones.

Beauty

Nurah works for a humanitarian organization. Homeless and undocumented for a long time, she is now giving back to others the help that she received. Egged on by her compatriots, she allows her portrait to be drawn. “Make sure you bring out my dimples!” she says. Beauty speaks for itself.

Double portrait

Mounir is 16 years old. He wants to show he is also talented and asks for a pencil and paper. From his mind’s eye, he draws the face of a girl with long eyelashes. “Is that your sweetheart?” his compatriots ask laughingly. He laughs too. Does she really exist? Will he find her again? Is she waiting for him?

Uprooted

Nader no longer knows at what point he turned off and took “the eternal detour”. After several long years of chaotic travel, he finally ended up in a camp where his only markers in the sand of time are his wandering past and a future that he has yet to glimpse.

His cigarette smoke swirls through the disjointed telling of his long, drawn-out journey. The borders crossed, the one-day encounters, the places that enticed him to stop and put down roots but were off limits. He is exiled from a land that has never recognized him, yet it remains the ground that has founded his identity. Is it possible to put down roots in reinforced concrete?

Each week, volunteers from the French Red Cross help migrants who are stranded in Calais, providing, among other assistance, family links services to put migrants back in touch with their loved ones. Artist Magali Massoud has sketched the portraits of some of the migrants.

They have survived one of the riskiest journeys of their lives. Every fibre of their being contains hope as they seek a better life, far from war and poverty. Mobile teams from the French Red Cross are working to improve these migrants' living conditions, offering them health care and a welcome break from their tedious situation. The Red Cross teams also provide a connection with their families through the restoring family links service. The rather dull name belies a range of human emotions, such as when a son calls his mother after long months of silence.