Helping the physically disabled in Afghanistan: A lifetime’s work

Kabul, November 2020 — On a crisp, blue-skied November morning, the Ali Abad Orthopaedic Centre in Kabul – a sprawling compound catering to the needs of some of the most disadvantaged people in Afghan society – is a hive of activity and enterprise.

In busy women's and men's wards, amputees – many of them land mine victims – are receiving physiotherapy or being assessed for new prostheses.

Some have been coming to the centre for many years - like 20-year-old Bibi Rahima, who lost both her legs when a rocket landed on her house nine years ago, killing her aunt and severely injuring other family members. She is on her third pair of prostheses and will require lifelong care, but is determined to finish her delayed schooling and one day become a doctor.

Others are having artificial limbs fitted for the first time and trying to take their first painful steps. One is Mohammad Aajan, a 28-year-old soldier in the Afghan national army who lost both his legs and an eye when his vehicle drove over a land mine eight months ago. He hopes that he will soon be able to walk again, and that the army will take him back, as he knows he is unlikely to find any other job opportunities.

A child with young carer waiting to be seen at the ICRC’s orthopaedic centre in Kabul. Photo: Mohammad Masoud Samimi / ICRC

In the children's ward, most of the young patients are suffering from cerebral palsy, some being seen for the first time after travelling long distances with anxious family members. The queue outside is several dozen long.

Elsewhere, in the centre's various workshops, technicians are busily producing everything from prosthetic limbs and plaster casts, to crutches and wheelchair parts.

Nearby is an internationally certified school, where people with disabilities are taking a diploma course to become qualified prosthetic and orthotic technicians. And – with pride of place – a sports hall where some 300 wheelchair basketball players train and play, including the national team.

Alberto Cairo, the charismatic head of ICRC's vast orthopaedic programme, says that the current level of activity is still much lower than normal. "Due to COVID-19, we initially had to suspend 80 per cent of our usual services and we couldn't take any new patients," he says.

"We have the necessary Personal Protective Equipment and implement physical distancing as much as possible, so things are slowly picking up again, but not like before. At least 25 per cent of our services remain suspended, mainly for in-patients and the referral programme. It is very sad."

"At least 25 per cent of our services remain suspended, mainly for in-patients and the referral programme. It is very sad."

— Alberto Cairo, head of ICRC's orthopaedic programme

"It's not as if we're a factory making toys or consumer goods that can close any time. People absolutely depend on us. Many of our services are not available anywhere else, so it's vital that we continue, no matter what," he adds.

Alberto says that demand for certain services is so high that there is now a waiting list of some 900 children with cerebral palsy, with at least a six-month backlog – due at least in part to COVID-19. "COVID here is just one more threat among so many others," he says. "People need to work to eat and live. Lockdown would be impossible. People have no choice but to take risks when they're struggling to survive day to day."

Since the orthopaedic project started in 1988 in Kabul, it has grown exponentially ever since – now comprising seven rehabilitation centres across the country. About 190,000 physically disabled patients have been registered since then, of whom at least 150,000 per year receive treatment at one of the centres.

About one quarter of them are amputees – mostly victims of mines and explosive remnants of war – while the rest include sufferers of polio, spinal injuries, congenital deformities, cerebral palsy and accident victims, among others. Some of them need treatment for many years, often for the rest of their lives.

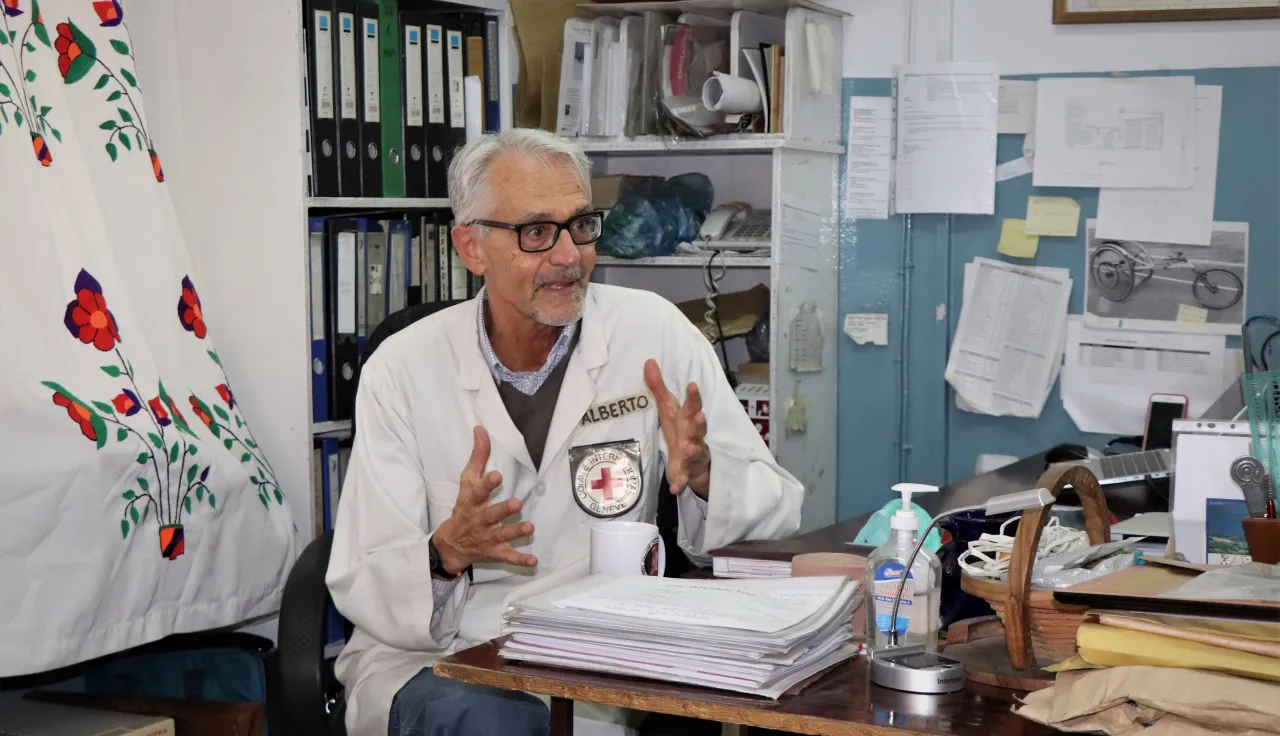

Alberto Cairo, head of the ICRC’s physical rehabilitation programme in Afghanistan, in his office at the Ali Abad orthopaedic centre in Kabul. Photo: Mohammad Masoud Samimi / ICRC

For Alberto, who arrived in Kabul from his native Italy in 1990, it has been his life's work to build up the ICRC's physical rehabilitation programme into what it is today. One of the many remarkable things about the orthopaedic centres – and in Alberto's eyes one of his greatest achievements – is the fact that nearly all the 815 staff themselves have disabilities.

"We implemented this positive discrimination policy from the very start, only employing physically disabled people to work in the centres," says Alberto. "It is good for everyone. The staff understand the needs and challenges first-hand, and for the patients, it gives them hope and motivation," he adds. "It was hard work at first convincing people this would work – even the ICRC – but I was absolutely determined. Today we are much more focused on inclusion and I don't think anyone would reasonably question the logic of what we are doing here now."

The staff understand the needs and challenges first-hand, and for the patients, it gives them hope and motivation.

Staff at the ICRC’s orthopaedic centre in Kabul assembling parts for prosthetic limbs. Photo: Mohammad Masoud Samimi / ICRC

When there were no more jobs available, Alberto started up vocational training and micro-credit programmes – initially for paraplegics and eventually for all patients with disabilities. Over the years, almost 11,000 small loans have been given out for enterprises such as tailoring, carpentry, welding, or petty trade in firewood or fruit and vegetables.

"This scheme really offers some hope and opportunity for people who otherwise would have few, if any, prospects," says Alberto. "Unfortunately, this is another victim of COVID, as we've had to scale back considerably for the time being at least."

For Alberto, one of the most exciting developments in the programme has undoubtedly been the growth of the sport in recent years, particularly wheelchair basketball. "Even I used to think that sport for people with disabilities was more of a luxury than a necessity," he says, "but there are so many positive aspects. Physical rehabilitation and inclusion and just simple fun. It's pure joy to see."

Mohammad Aajan, 28, having prosthetic legs fitted for the first time at the ICRC’s orthopaedic centre in Kabul. Photo: Mohammad Masoud Samimi / ICRC

The fact that Afghanistan has national wheelchair basketball teams successfully competing abroad – with players being treated, albeit briefly, as celebrities - has helped perceptions a lot, according to Alberto. "It has helped people to understand that disability does not preclude a normal life – or as near to a normal life as possible," he says.

At 68, and now an honorary Afghan citizen, does Alberto plan to retire in the near future? "I need to keep being useful to be happy," he smiles. "So even if I retire, I will stay here and remain involved in disability and sport in one way or another. But I have a dream job, and I'm not ready to stop quite yet. There's still a lot to do."