"People deserve to rest in peace - it matters"

What responsibility do we have to the dead? An ICRC forensic specialist reflects on this sometimes harrowing but always meaningful area of work.

Oran Finegan recently left his role as head of the ICRC forensic team to take up a new position as forensic specialist in Thailand.

Journey to the ICRC

I had worked in forensics for years, with the UN and International Crimes Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, in the Balkans mainly.

The work was very meaningful, but by 2003 I needed a break due to what I had seen and experienced.

I hadn't realised it at the time, but my mental health had greatly suffered.

I went on to study human rights and political theory at the University of Essex in Colchester and it was there that I discovered more about the ICRC and about its role in international humanitarian law which I found fascinating.

After that, I was on the path of wanting to work with the Red Cross in conflict zones. Finally, in 2008 I was able to merge both fields that were very close to my heart: humanitarian work and forensics, by joining the ICRC as a forensic adviser.

I was one of the first members of the ICRC forensic team. I joined back in 2008, when there were just five of us – now the unit comprises almost 100!

What does the forensic unit do?

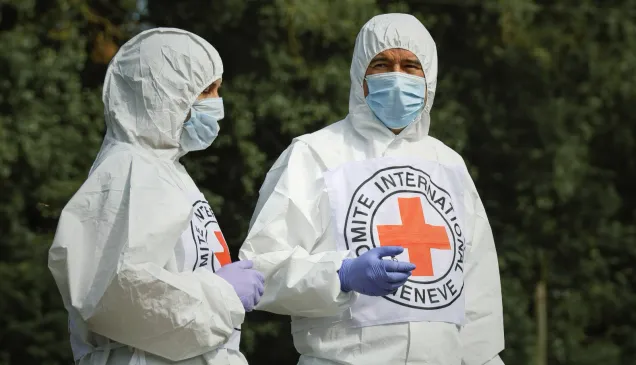

The ICRC works hard to stay at the forefront of humanitarian forensics so that the team can provide the most appropriate help to those affected. Their work is varied, but includes:

• Supporting local authorities and experts searching, recovering and identifying the dead, both to prevent and resolve the tragedy of people unaccounted for as a result of conflict, violence, disasters and migration.

• Helping first responders with the management of the dead, making sure that the deceased are protected and treated with dignity and respect.

• Applying forensic knowledge and expertise to help address the humanitarian needs of those affected by conflict and disaster, and also ensure the protection of the dead in line with International Humanitarian Law (IHL).

Today, the ICRC has experts from fields including forensic genetics, anthropology, odontology, archaeology, and pathology working as part of their forensic team.

The right to rest in peace

Growing up in Ireland, I felt that death or the dead was something that played an important part in people's lives. The festival of Samhain (Halloween) for example, was something that had fascinated me from an early age, in view of how the dead very much lived on in people's lives. There is the tradition of wakes and having very close proximity to the dead.

It was something that I believed was important, in terms of understanding the need to protect the dead, to treat them with dignity and respect.

When you look at the common expression 'rest in peace', I think that's a very important statement. People do deserve to be able to rest in peace.

Look at how we've thought about the dead historically. Why did people put money in the hands of the dead to pay the ferryman on the way to the next world? Or leave an empty place at the dinner table on the festival of Samhain to remember a family member who had departed? It was considered important to ensure that those who died would rest in peace, in the way that addressed the beliefs of those concerned.

I think that's vital in terms of our thinking, and what our role is.

A personal connection

I'm sure that in death, that we ourselves would want to rest in peace.

When my father died, he asked for his ashes to be spread on a specific beach, near where I live, and when I go there, either alone or with family, and I see and feel the peace, I understand why it was something that mattered to him. But also, how important it was for him, in his own mind, to know where he would rest and for us to have a focal point to remember him.

The issue of the missing has also had a very personal importance for me.

My uncle, like many Irish people, went to London and disappeared. Like many Irish people who journeyed across the sea, he remains missing.

I saw the impact that had on my father and the pain and suffering of not knowing. It had a profound impact on me.

Protecting the dead

Something that has been very important to me is changing the narrative around the dead.

I think, as forensic practitioners, we've come to understand the idea of protection of the dead and not simply 'dead body management'.

Of course, it's about handling bodies in a dignified way. But it's much more than that.

We often think of the role of forensics in relation to the living – identifying the remains of loved ones helps families to know their fate. And that is very important. But we also have a duty to the dead themselves. They also have rights. The right to be buried or cremated according to their beliefs, the right to rest undisturbed.

Then you look at death in conflict, at how the dead are subject to desecration, sometimes in retaliation for previous events, to instil fear in communities, how the dead are often used as currency in conflict, exchanged for prisoners, and even as a weapon of war in some circumstances.

The importance of protecting the dead is one that is rooted in international humanitarian law and I think it's a very powerful message.

I'm proud that we're now seeing that in terms of the way we deliver our programmes, and how we think of the dead in conflict. I think that's been a very important change.

Part of a bigger picture

It's vital that when we're applying forensic knowledge to a case or to a situation we also have an understanding of, and engagement with, the affected communities.

We mustn't just look at forensic practice, but how our work fits in with cultural and religious issues.

This year with the Covid-19 pandemic, we combined our experience with that of our community engagement team, to really begin to understand what affected people needed, as opposed to what we assumed.

We saw that many bodies were buried unidentified. Bodies were incinerated, not for religious reasons, but for perceived public health reasons, which was completely unnecessary. We worked with communities and with local authorities to address those issues.

Listening to communities

Listening to communities and understanding their cultural and religious needs is fundamentally important. What may appear to us as the best course of action may indeed be highly offensive or even dangerous for the communities concerned.

We must remember that for some communities, burial may be unacceptable, and the exhumation of the dead may indeed cause great offense. Examples of this include following the Holocaust, with the outcry from some of the Jewish community over exhumation of mass graves, and how that was a second atrocity being inflicted upon them.

We need to ask, what is the impact on these communities? What does it mean? What matters to them?

Everyone has a right to know, everyone should have a body to identify. But we shouldn't make the assumption this is what everyone wants.

The world is a patchwork of cultures and we must remember this. We need to listen to affected communities first and design our programmes of work around them. I think that's critically important.

For me, something that particularly stands out is the work I did with Ahmed Al-Dawoody, ICRC's legal advisor on Islamic law, looking at IHL, Islamic law and the dead. This included an article looking at how forensic science and Islamic burial laws can ensure dignity of the human remains of individuals who have died from the pandemic.

The impact of Covid-19

I think the Covid-19 pandemic has definitely had an impact, both inside and outside the ICRC, when we look at how people view death.

The importance of respecting the dead has been brought home to all of us. Death has come into our own sitting rooms so to speak.

Perhaps now we all have a better understanding of the cultural importance and the impact of the dead not being respected. And you know, that's something I've spent my working life seeing.

That's true for my colleagues also. We've walked into morgues that are overflowing, with bodies piled up and nowhere to put them. And we know that it matters.

It matters to families, it matters to those working in these forensic facilities and hospitals.

It matters that we do something, that we work to develop appropriate facilities, to ensure that preparedness is there, so that when people do die, we can ensure their burial, or cremation, in line with cultural and religious needs, and that they are known.

Ultimately, it's about integrity, human dignity... respect.