Tragedy at Evros: A perilous river crossing to Greece

Basheer thought he could make it. He was 18, in good health and knew how to swim. But the Evros River crossing takes many victims.

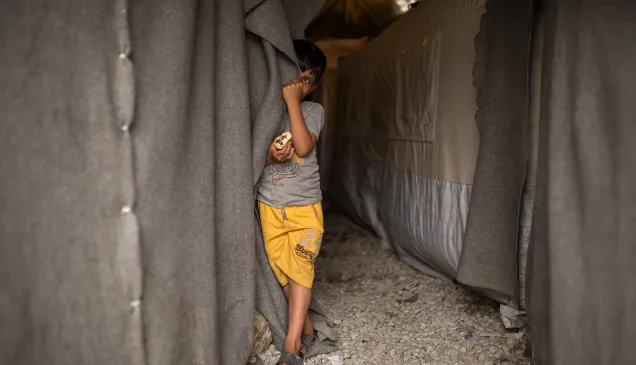

Wet, cold, tired and lost, a mother and son who successfully crossed Evros lay down on the riverbank afterward. Hypothermia killed both. Another family buried their 4-year-old near the river after a train hit her while the family was walking along nearby tracks.

For migrants fleeing violence or seeking better economic opportunities, the Evros River is a major milestone. Flowing down from Bulgaria's Balkan Mountains, the river traces the 150-kilometre border between Turkey and Greece before emptying out into the Aegean Sea.

Families – often with children and grandparents in tow -- cross this liquid portal into Greece and thus the European Union. Some use rickety boats procured by smugglers. Others, like Basheer, try to swim.

But the river – both milestone and portal – can also be a watery graveyard. Many migrants die here, including hundreds of people still not identified. The Red Cross Movement is working to improve forensic identification capabilities, to bring dignity to the dead and closure to grieving families.

Basheer's body was discovered a month after he plunged into Evros' cold waters. The only documents found on him were a phone card and an unreadable passport, meaning that authorities could not identify the teenager.

"Evros has the largest number of buried and unidentified migrants in Greece," said Dr. Pavlos Pavlidis, a forensic pathologist at the General Hospital of Alexandroupoli who has worked on many cases of deceased migrants.

Dr. Pavlos Pavlidis, Forensic Pathologist, General Hospital of Alexandroupoli. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / Stylianos Papardelas

Many of the migrants who try to cross when water levels are high don't escape the fast current, Dr. Pavlidis said. Their bodies are found when the river's water levels drop again.

Statistics on how many people cross the river are scarce, and reliable information on those who die while crossing is even scarcer. The U.N. says some 6,500 migrants are waiting to cross Evros from Turkey, a crossing unintentionally made more popular after a European Union agreement with Turkey to curb new arrivals to Greece's islands by sea.

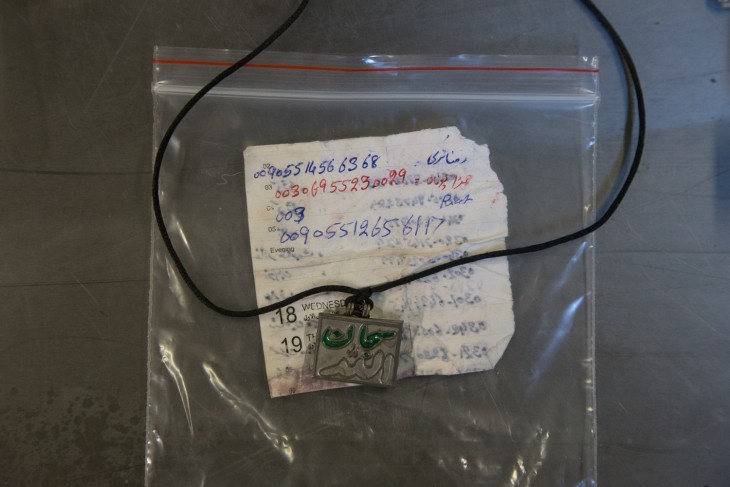

Personal belongings are often left behind by missing migrants. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / Stylianos Papardelas

Crossing the Evros is safer, but the river still holds hidden dangers.

Families in Greece who live near the river say that seeing migrants traversing their land is common. These farming communities frequently open their doors, giving out food and water to those in need. Sometimes they become true life-savers.

One freezing winter day a group of farmers boating along the river spotted a young Pakistani man soaked and dangerously cold. "The poor guy was so wet. He was shivering and unable to talk," said Tasos Salikiriakis, 43, a resident near the river.

One farmer gave the Pakistani man his jacket; another one gave a pair of pants; and yet another one a pair of socks. They put him in their car to heat him up. The disoriented Pakistani asked for a cigarette.

"He could not stop thanking us after that. He was hugging us for giving him clothes," said Salikiriakis. "We gave him brand new clothes and joked that now he is ready to get married," a reference to a common Greek saying.

The Greek residents were about to leave when the Pakistani man, using broken English, said there were more people in the river. The farmers called border guards, who lit a fire on arrival and handed out warm, dry clothes to the cold – and scared – migrants.

In summer months most migrant deaths come from drownings. In winter, the biggest killer is hypothermia, said Pavlidis, the forensic pathologist.

"When people cross the river and reach the land, they think they are safe because the worst has passed. Most of the time they find shelter in abandoned farm warehouses to spend the night, fall asleep in wet clothes and never wake up," said Pavlidis.

It's exactly that kind of case that gives morgue assistant Poppi Lazaridis goosebumps. A father, mother and child crossed the Evros during the winter. The mother, whose extremities were frostbit, could no longer walk, so the father left his wife and child to seek help.

Poppi Lazaridis, Morgue Assistant, General Hospital of Alexandoupoli. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / Stylianos Papardelas

But when he returned he couldn't find them. By the time the pair were finally located they were both dead. It is the worst thing Lazaridis has seen in her line of work.

"There is nothing worse than a child who has to sit with his dead mother out in the cold at night," she said. "I was crying for three days after this case. I was praying to God and hoping that the boy died before his mother."

All unidentified bodies in the region are examined in the General Hospital of Alexandroupoli, the closest major city to the river crossing. A DNA sample is collected and held in a national DNA database.

The body of Basheer – the 18-year-old who tried to swim across the river – was among those examined by Pavlidis. He took a DNA sample and assigned the teen an identification number in case his family would ever look for him.

Three months later a man approached the Hellenic Red Cross Tracing Service asking for help to find his son. With the support of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Greek officials collected a DNA sample. A positive match with Basheer was found.

Confirming the death of a missing family member is always a tragic closure, said Jan Bikker, the ICRC's regional forensic expert. "But at least the family could now put an end to its agony and had a place to mourn their lost son. This is the first step to the long route for recovery."

Not all cases bring such closure. Between 2000 and 2017 some 352 bodies were discovered in the region, but only 105 were identified. Migrants may not carry documents and are often separated from the group they travel with, making it difficult to gather information about them. Decomposed bodies further complicate the identification process.

Forensics involve the collection of personal items of missing migrants. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / Stylianos Papardelas

Unidentified bodies are kept in the Alexandroupoli hospital refrigerators for up to four months. If they remain unidentified they are sent to Sidiro, a village 65 km north of Alexandroupoli, to be buried by the village mufti, as many migrants come from Muslim majority countries.

The ICRC forensic team in Greece is assisting authorities not only on the proper identification of dead migrants but also to ensure proper management and dignified burials.

"The bodies of people who perish while crossing the river or shortly after often remain unidentified for a long time and relatives may not know what has happened to their family member. Their fate remains uncertain but people have the right to know," said Bikker. "When bodies are collected it is important to identify them and to bury them in a dignified manner and in such a way that they can be identified and located later."

Personal items of missing migrants provide a means of identification. CC BY-NC-ND / ICRC / Stylianos Papardelas

The Greek residents who live near the Evros are familiar with the dangers of migration. While they often hand out free food or clothes, sometimes they have to go a sad step beyond and arrange a funeral.

A family escaping the violent horrors in Aleppo, Syria crossed the river with their four children in November 2015, riverside resident Akis Armparzanis recalls. The family paid $20,000 to smugglers to get them to Greece.

At around 10 p.m. that November night, the family was walking on railroad tracks near the river when a train approached. The family's 4-year-old fell down as the train was passing, and the train hit her head.

"The family ran to the village where we were," said Armparzanis. "They were crying and screaming, trying to explain what happened."

Paramedics tried to revive the child but couldn't. Residents helped pay funeral expenses. The Syrian family has settled in France, but sometimes returns to the Evros to visit the grave of their child, evidence of the strong family desire to not only know the fate of a loved one, but to also know that family member's final resting place.

Steps are now being taken in Greece to develop a legal framework better equipped to coordinate the management of unidentified bodies. The ICRC is assisting with dead body management by donating a refrigerator unit, body bags, and DNA kits to support Dr. Pavlidis and his team.

"People have fled war and poverty searching for safety and a better life, but many have only found death," said the ICRC's Bikker. "Through our work we can at least try to restore the dignity and respect they deserve."

For further information, please contact:

Lucile Marbeaut, ICRC Paris, tel: +33 (0)1 56 54 11 19

Fragkiska Megaloudi , ICRC Athenes, tel: +30 694 871 63 27

Elodie Schindler, ICRC Geneva, tel: +41 79 536 92 48