To discuss humanitarian concerns about, and challenges posed by the proliferating cases of urban armed conflict around the globe – particularly in African cities – the ICRC convened a regional panel discussion of experts in June 2017 in Kigali. The event was part of a series of such conferences on "War in Cities" organized by the ICRC. The aim is to discuss current trends and their implications for humanitarian action.

The panel brought together national and regional experts from the humanitarian, military, diplomatic and academic communities. It sought to address emerging questions such as the following: What has the world learned from past urban conflicts and other violence, notably in South Sudan, Nigeria, the Central African Republic, Somalia and Côte d'Ivoire? What had been the implications of these urban conflicts on humanitarian action and policy? How could the main local and international entities involved best work together to improve the situation of the civilian population, ensuring that expertise is drawn from a wide variety of sources?

Opening remarks

- Joëlle Germanier, Outreach advisor, ICRC

- Pascal Cuttat, Head of Delegation, ICRC

Moderator

- Alice Karekezi, Researcher and Lecturer, Centre for Conflict Management of the University of Rwanda

Panelists

- Adama Dieng, UN Secretary-General's Special Adviser for the Prevention of Genocide

- Jean-Paul Kimonyo, Rwanda - Expert on conflict and post-conflict reconstruction; Senior Advisor on NEPAD Office of the President, Rwanda

- Colonel Jill Rutaremara, Director, Rwanda Peace Academy

- Julien Le Sourd, Urban Water Advisor, ICRC Nairobi, Kenya

A matter of great concern in Africa

While the most intensive urban conflicts in recent years had occurred mainly in the Middle East, the African continent had also been experiencing a shift from rural to urban hostilities, a trend that was likely to continue given growing urbanization. Adama Dieng opened the discussion emphasizing the importance of prevention efforts to ensure respect for international humanitarian law (IHL). "In Africa – like other parts of the world – armed conflicts are increasingly being waged in urban settings, with devastating consequences for residents," he said. "It destroys public facilities such as water-supply systems and hospitals, and often ruins people's means of earning a living." Noting that there was no lack of international treaties and other rules binding the countries concerned, Dieng deplored the level of violence observed in cities such as Bamako and Mogadishu. Referring to the impact of the use of certain highly destructive weapons in populated areas, such as explosive weapons, he stated "no exaggeration to say that these actions were depriving citizens of their very countries and their futures."

This new violence in cities requires a corresponding change in thinking about how to meet the challenge of armed conflict in Africa. Efforts have already been made to ensure that both States and armed groups adhere to IHL, which have led to African Union resolutions, statements of commitment and the integration of IHL into armed groups' military doctrines. However, on addressing the changing landscape of IHL violations, Dieng emphasized the need for a strong accountability framework which recognizes that the protection of civilians should be a central component of further prevention efforts. He concluded by recalling "It is critical that States recommit to IHL to ensure protection of civilians and urban infrastructure".

What challenges face humanitarian organizations?

Speaking next, Julien Le Sourd set out the main challenges facing humanitarian organizations dealing with the effects of urban warfare in Africa. These challenges ranged from difficulty in gaining access to the people affected, to lack of funds, and on to the disruption of key basic infrastructure such as roads, health-care facilities, and water-supply systems.

Among the infrastructure most severely disrupted by urban fighting are water systems and sanitation facilities. If people accepted that "water is life", people necessarily accepted that destroying water-supply and purification facilities was today ruining the lives of a whole generation of people.

Le Sourd pointed out that the civilian population bore the brunt of urban armed conflict. In addition to being driven out of cities, becoming separated from loved ones in the chaos, and widespread death and injury, people also fell victim to a host of infectious diseases caused by the collapse of essential services.

Humanitarian organizations struggle hard to maintain people's access to essentials like food, water, shelter and health care. But they too often lack the long-term funding needed to meet both people's immediate needs and carry out vast and costly repair work on infrastructure.

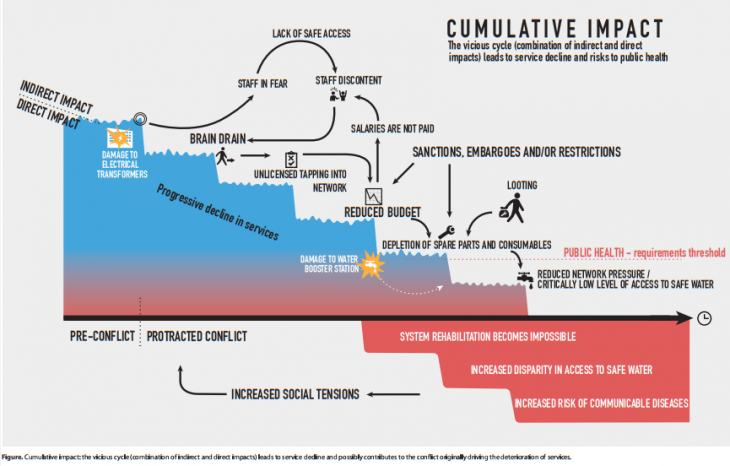

Another challenge was the shortage of local people with the technical skills needed to repair and maintain these facilities. This shortage was exacerbated by the brain-drain effect of protracted conflicts (see diagram below).

Le Sourd called on all those involved – State and non-State armed groups, humanitarian organizations and others, including donors – to work together closely for a more effective and efficient response to people's long- and short-term needs.

Legal implications of, and challenges posed by, urban warfare in Africa

Speaking from the military perspective, Colonel Jill Rutaremara recognized the increasing shift toward armed conflict in urban settings and the asymmetric nature of that conflict in places like Mogadishu, Tripoli and Bangui.

Rutaremara outlined the main IHL rules and principles applicable to urban warfare, focusing on the principles of distinction, proportionality and precaution. He stressed that these principles were crucial for military decision-making on the means and methods to be used in urban warfare. Nevertheless, he emphasized that the variations in nature and level of development of cities and the motivation and capabilities of belligerent parties, make wars fought in cities complex and called for detailed analysis of civilians' needs.

He put forward a number of suggestions on how to improve the protection of civilians and critical infrastructure; "it is important to select the appropriate means and methods of warfare, conduct military training in IHL and engage in closer cooperation between the belligerent forces and humanitarian actors. Besides, the incorporation of IHL in national legislations, military doctrine and codes of conduct and manuals, together with clear rules of engagement and context specific operational orders are fundamental. Last, but not least, lessons learned and good policy practices on mitigating civilian harm should be shared with the view to adopting those that are relevant and context specific".

Elections: no guarantee of peace and good governance

Dr Jean-Paul Kimonyo, who approached the topic from a political viewpoint, started by outlining what he viewed as a "new wave" of African uprising and revolt in reaction to poverty, unhealthy environments, poor services and the disadvantages of social class systems. He calculated that since 2005, the number of protests and riots in Africa had multiplied tenfold, and most of these occurred in cities.

"If well managed," he said, "urbanization constitutes an opportunity for economic development. However, what we are seeing in Africa is instead an expansion of the slums. We are seeing impoverishment and rising inequality. Social divisions and identity politics serve as fertile ground for protests, riots and even urban wars." Kimonyo felt it obvious that there was a link between elections and violence, with African cities being at the heart of protests and even revolutionary movements. Citing as examples Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya, he said that "even relatively stable countries were prone, at election time, to outbursts of violence".

A way forward Kimonyo stressed was devising election processes that focused on power-sharing instead of competition. The supreme aim should be voting as a democratic and peaceful event. First, election campaigns needed to be discussed frankly in international forums, including the African Union, rather than being the object of alarmed reaction after the fact. Second, humanitarian organizations should stop viewing elections as a benchmark for progress in civilian welfare. On the contrary, an election should be regarded as a red flag signalling the need to strengthen protection in the long and medium term. Third, local communities and organizations should work directly toward confidence building and mutual protection in the run-up to elections.

Ensuring better protection of civilians

The common desire mentioned by all speakers and the audience was better protection of civilians during urban armed conflict.

The panel concluded that doing more to protect civilians, their property and facilities for their welfare required that both State and non-State entities publicly commit themselves to respecting and ensuring compliance with IHL. African countries must continue working to incorporate IHL into their domestic law. They must also do more to hold accountable those who breached the law.

Speakers emphasized the urgent need for local and international entities to look again at the planning and organization of African cities in a way that promoted protection of civilians. They highlighted the need for sound leadership that promoted equality and equity as a means of preventing armed conflict and other violence in the first place.

Finally, they advocated the creation of discussion platforms on the African continent to encourage critical thinking and awareness-raising on these issues of great concern.

Watch the full conference video: