Colombia: 2025 set to be the decade’s worst year in humanitarian terms

During the first half of 2025, the humanitarian situation in Colombia deteriorated considerably, with increasingly severe consequences for civilians. The adverse impacts suffered by communities exceeded those recorded during the same period in 2024. If this trend continues, in humanitarian terms, 2025 will be the worst year of the past decade.

The deteriorating situation was closely linked to the increase in fighting between the national security forces and armed groups, as well as fighting between different armed groups. The hostilities had particularly serious consequences for civilians because of the repeated failure to respect the principles of distinction, proportionality and precaution under international humanitarian law (IHL). Armed groups exerted ever tighter controls on civilians which, in many cases, resulted in them being threatened, mistreated, displaced, their movement restricted and their daily lives being severely disrupted in other ways.

The ICRC is also concerned about communities being increasingly stigmatized and exploited. In several regions, people have been targeted, accused of favouring one party to the conflict or another, and subjected to pressure that puts them at risk. This has increased their vulnerability to various forms of violence and weakened the fabric of society. The consequences have been particularly serious in terms of threats, restrictions, displacement and difficulties in accessing essential services.

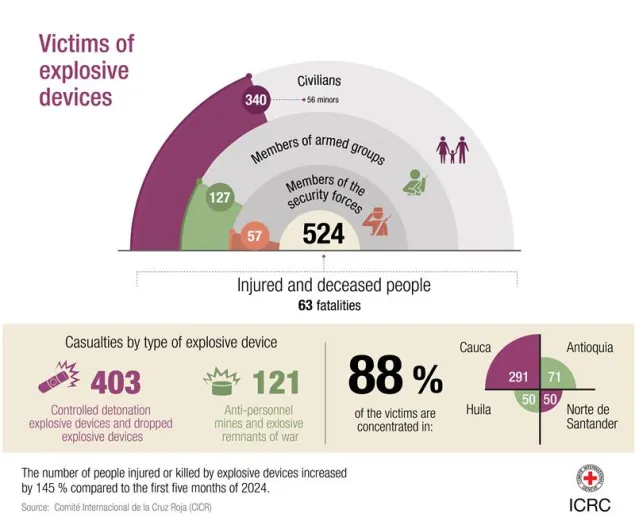

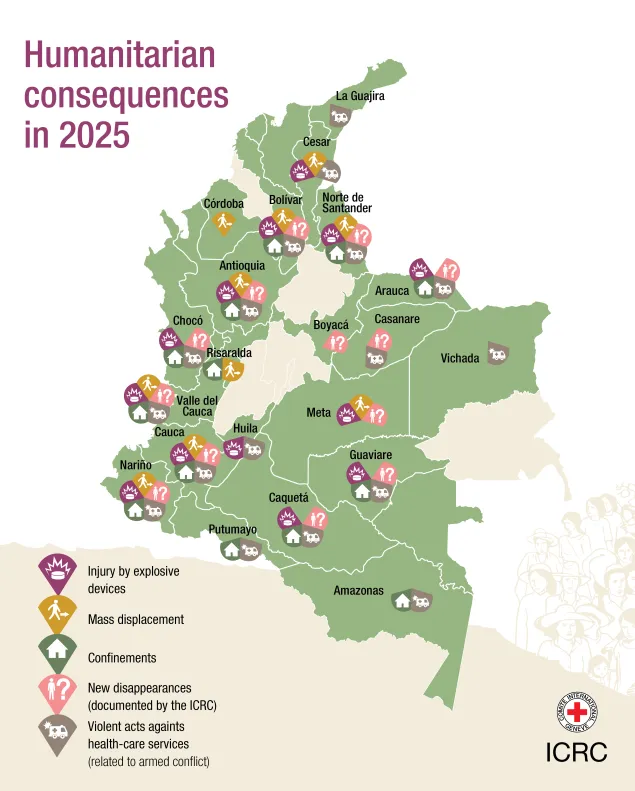

One of the most worrying trends was the increase in the presence, use and abandonment of weapons, munitions and explosive devices, such as anti-personnel mines, explosive remnants of war, launched devices and controlled detonation devices. Between January and May, the ICRC recorded 524 people wounded or killed by explosive devices – an increase of 145 per cent compared with the same period in 2024. Seventy per cent of victims were civilians – 56 of them children.

People in the department of Cauca suffered 55 per cent of the incidents, whereas Huila, which had no cases the previous year, became the third most affected department with 50 victims. The intensive use of explosive devices set off by improvised launchers and weaponized drones, as well as controlled detonation devices, was the main factor behind this increase. There were 137 people wounded or killed by launched devices, an increase of 342 per cent, and 266 victims of controlled detonation devices, an increase of 343 per cent. Victim-activated devices, such as anti-personnel mines and explosive remnants of war, continued to claim a high number of victims: 121 in total.

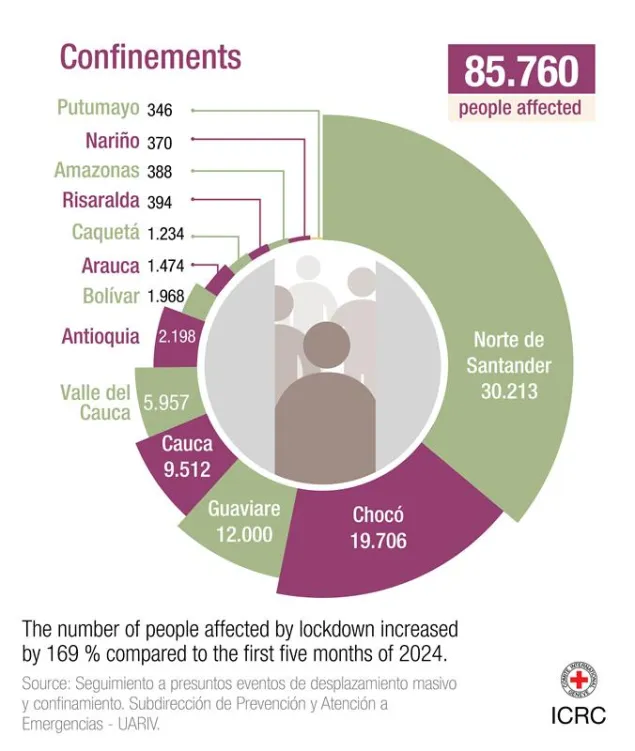

Confinement also had a considerable impact on people. According to official figures for the same period, 85,760 people were confined across 13 departments – an increase of 169 per cent compared with the first five months of the previous year. Norte de Santander, which had not reported any confinements in recent years, was the most affected department during this period, with 30,213 people confined. This was followed by the department of Chocó, with 19,706 people affected. The problem had also spread to other departments, such as Guaviare and Amazonas, where no confinements had been recorded in recent years. In these areas, entire communities were left without access to safe drinking water and food, health services and education, which reduced their autonomy and ability to organize collectively.

Mass displacements also increased. Between January and May, 58,160 people were displaced across ten departments, an increase of 117 per cent compared with the same period in 2024. Norte de Santander was once again the most affected region, with 49,808 people displaced. In contrast, Nariño, which used to have the highest figures, reported a 92 per cent decrease, an unusual trend compared with the rest of the country. Added to this was the issue of individual displacement, a less visible but equally serious problem. A total of 87,461 people were included in the Single Registry of Victims for this reason alone. Many of these people silently left their homes, fragmenting their families and upending their lives. The consequences of this issue are yet to be fully recognized.

People going missing continues to cause pain and suffering. Between January and May, the ICRC documented 136 new cases in relation to armed conflict, with 81 per cent of them civilians. Among the missing are 26 children. Eight of these cases were related to the recruitment and participation of children by armed groups, which shows a direct link between both of these humanitarian consequences.

The recruitment, use and participation of children and adolescents are serious violations of IHL – and a problem that has become more acute in 2025. Although the ICRC does not publish its own data, its work on the ground and discussions with communities mean it has a good understanding of the scale of the issue. The recruitment, use and participation of children disrupts their lives, exposes them to multiple forms of violence and leaves deep scars on their communities.

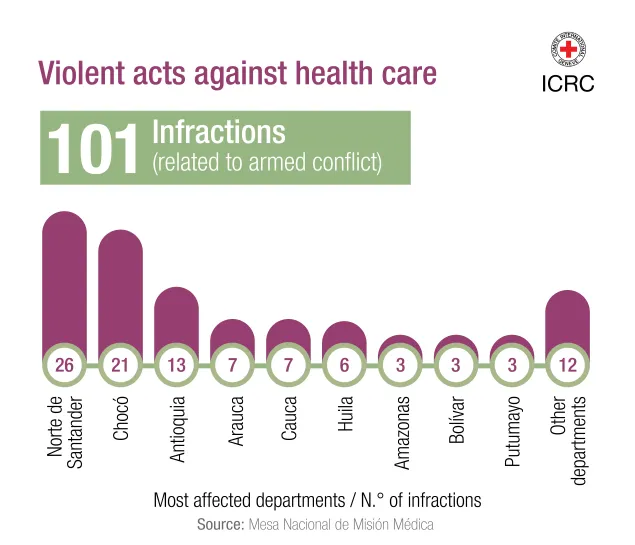

Between January and May, the Mesa Nacional de Misión Médica (National Medical Mission Board) reported 101 incidents related to armed conflict, an increase of 38 per cent compared with the same period in 2024. Among the events recorded are threats to health-care staff, restrictions on people accessing services, demands for care to be provided in inappropriate conditions, hindering the treatment of injured people, and a lack of protection afforded to health-care staff, facilities and ambulances. These situations compromised the work of health-care staff and access to essential services for thousands of people in the areas most affected by armed conflict. Some 59 per cent of the incidents recorded took place in the departments of Norte de Santander, Chocó and Antioquia.

Furthermore, this increasingly complex environment has also had an impact on humanitarian access. Security conditions, restrictions imposed by some armed groups and a decline in funding have hindered the ability of impartial humanitarian organizations to alleviate people’s suffering. These conditions combined not only hinder the provision of timely assistance, but also make it difficult for organizations to identify the risks communities face, mitigate the humanitarian consequences of conflict, and appropriately document the reality experienced by thousands of people.

During armed conflict, respect for IHL is not an option but an obligation. Compliance with IHL is critical to protect those who are not taking part or have ceased to take part in hostilities. Although IHL does not stop violence, it does establish clear limits to prevent unnecessary suffering, protect human life and dignity, and help preserve a minimum of humanity in the midst of war. Disregard for IHL only deepens the damage caused, prolongs suffering and further weakens the social fabric of affected communities.

During the first five months of 2025, there were ongoing concerns about conditions in Colombia’s places of detention. Overcrowding in Instituto Nacional Carcelario y Penitenciario (INPEC) facilities reached 28 per cent, adversely affecting detainees’ access to food and health care and their general living conditions. In temporary detention centres, overcrowding reached 122 per cent in police units and 15 per cent in Unidades de Reacción Inmediata (URI).

Media enquiries contact

Lorena Hoyos, ICRC, Bogotá

Public Relations Officer

Phone: +57 310 221 81 33

Emaill: bhoyosgomez@icrc.org

Media enquiries contact

Laura Santamaría, ICRC, Bogotá

Communication or Comm/Prevention Manager

Phone: +57 311 491 07 89

Email: lsantamariabuitrago@icrc.org