Mazyuna in her bedroom. Her son is imprisoned for life, but she keeps an empty bed for him next to hers. Several years ago she had a stroke that made her lose her eyesight. For four years she has lied to her son, pretending she can see him.

Between walls and rumours: women on the margins of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

“I can’t see him. I almost can’t hear him. Still, I would never miss a visit. Knowing he is close means so much,” says Mazyuna.

Mazyuna takes out her festive dresses. She never wears them anymore, unable to celebrate or rejoice.

Mazyuna leaving her house before dawn to visit her son. She says she never sleeps the night before the visit.

Mazyuna waits to cross into Israel. Vendors at the checkpoint know her well, because she has been using it for the past 30 years.

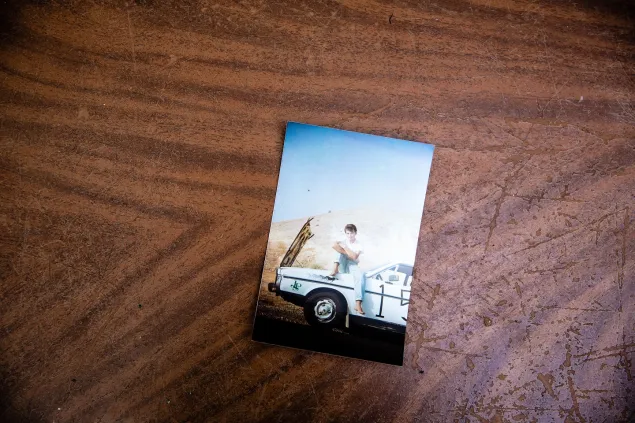

Once Mazyuna was allowed to touch her son and take a photograph together with him.

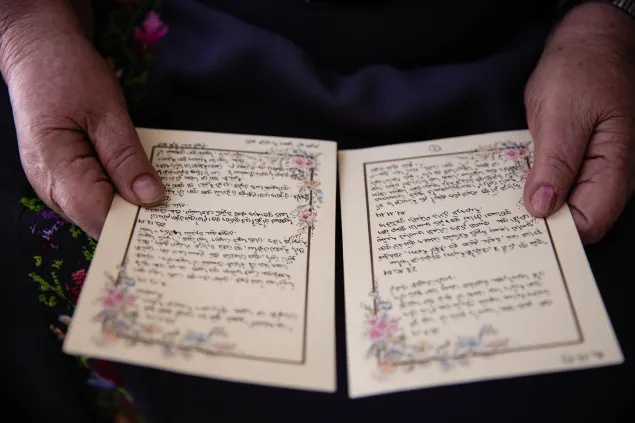

The eldest daughter in the family, Mazyuna had to take care of her siblings and never learned to read. Whenever someone comes to visit, she asks them to read her son’s letters to her out loud.

Mazyuna on the way to prison. Even before she arrives, she dreads the moment the visit will end.

Iman on the way to visit her husband in prison. Iman is 40. Married at the age of 18, she lived with her husband for only two years before he was arrested.

Iman and other relatives of Palestinian detainees on a Red Cross bus on their way to prison. Some 100,000 prison visits take place every year.

The prison visit is the most important event of the month for Iman. She prepares for it well in advance.

“I long for the day of the visit and feel empty afterwards. When they cut the phone, I keep knocking on the glass,” says Iman.

Iman now lives with her elderly mother and the memories of her detained husband. Taking care of her sick mother helps Iman fill her days.

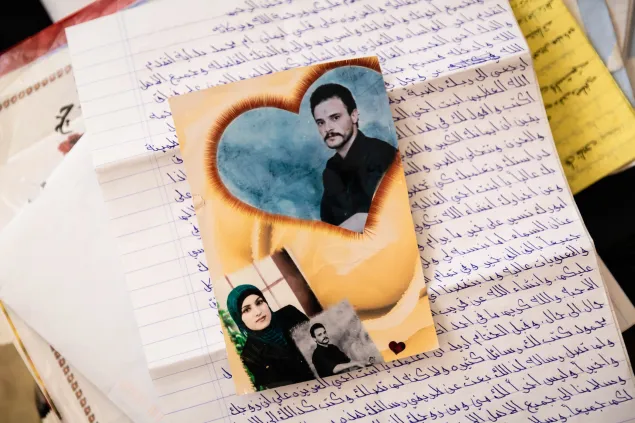

Iman does not have any photos with her husband. She takes their old pictures and photoshops them together.

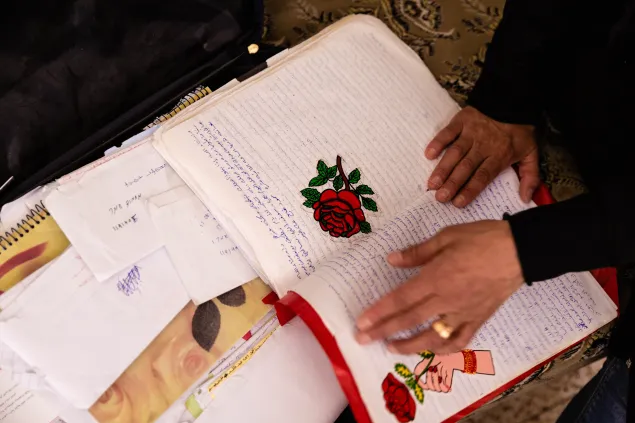

Iman has a suitcase full of letters from her husband. She keeps all of his old clothes.

Palestinian women waiting at the checkpoint to cross into Israel. “This is our life,” Iman said looking at the picture.

Iman’s permit allowing her to enter Israel has expired. She is waiting to receive a new one.

Fatmeh in her village on the outskirts of Hebron.

Fatmeh has lived with her mother-in-law since her husband was arrested.

Fatmeh got her daughters out of bed at five in the morning to catch the Red Cross bus that takes her to visit her husband in prison in Israel.

Some 6,000 Palestinian security detainees are held in Israel. Their wives and mothers travel up to 12 hours to see them once a month for 45 minutes through a glass separator. Prisoners receive a lot of attention, while the women visiting them remain largely unseen.

Invisible victims of the conflict, wives and mothers of Palestinian detainees organise their lives around prison visits. At the same time, they have to navigate a complex system of permits and checkpoints in the occupied West Bank, while trying to keep their families and community together.

Mediating between prison and family life, they are isolated physically by checkpoints and socially because a woman living without her husband is often subject to scrutiny and the power of rumour.

The wives and mothers of detainees we spoke to didn’t show any sign of happiness or the ability to go out and live a normal life. Whether these limitations are self-imposed, a sign of mourning for absent loved ones or an obligation towards society, they define these women’s lives and create their shared sense of identity. Over the past year, we accompanied Iman, Fatmeh and Mazyouna on their journey.

The International Committee of the Red Cross has been facilitating family visits for Palestinian detainees in Israeli detention facilities since 1968. Over 3.5 million visits have taken place to date.