Tuba village is located 2 kilometers away from the town of Yatta. Since early 2000, the villagers are not allowed to use the main access road due to the proximity of the outpost. Now, the villagers use a 12 km detour road

Masafer Yatta: Living in fear of losing your home

Huda in front of her demolished house

Difficult access to the area affected all aspects of life: access to water, education, health care.

Um Mohammed and Abu Mohammed are traditional cave dwellers. “We never open a water tap, Um Mohammed says and adds, “This would be such a waste. We cherish every drop.”

Local herders lost access to large parts of their agricultural land due to the settlement expansion.

Stones used to mark land ownership.

Radwan and Hael are brothers. As family lost access to two-thirds of their grazing land, Hael decided to move to the town of Yatta and get a job. “My heart, my spirit are still here,” he says.

Unable to use the direct access road, local herders suffer financial losses as fodder prices go up.

Saleh studies law at Hebron University. To get to classes, he takes a one-hour donkey ride through the mountains to reach the closest town and then a bus from there. He spends an average of four hours on the road every day.

Water is the most precious commodity in Masafer Yatta. It is much more expensive here than in other localities.

Access to education is particularly difficult for the girls, as parents are afraid to let them make the long trip alone.

As summer temperatures rise, cattle consume more water.

Despite all the hardship, residents of Masafer Yatta take pride in their hospitality.

People in Halawe village say that the place received its name because its land smells sweet.

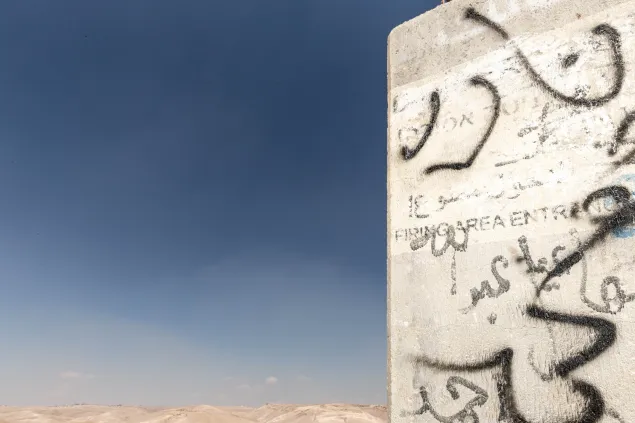

In 1977, the area was declared a firing zone by Israeli authorities. All new construction was prohibited.

Reem arrived at Halawe four years ago as a young bride. Having a house of her own has remained an unattainable dream.

“When you have a home, you can close the door and feel safe inside,” Reem said on the day her house was demolished.

Traditional caves and pre-1980s houses are no longer sufficient to accommodate a growing population.

Some 1400 people live in the firing zone of Masafer Yatta.

The future of the community is uncertain.

“All I want is to be able to watch TV,” says Huda Awad, a 58-year-old widow looking at the rubble of what used to be her house. Huda moved to Tuba village, West Bank, when she was 20 after one of the local residents became her husband. In 1977, the area was declared a military training zone and all new construction was prohibited. But life continued its course, couples got married and children were born. People needed a place to live and built new houses.

Some demolition orders remain pending for years while others are executed quickly. For over a decade now, legal battles continue, while every family in this area of some 1400 inhabitants lives with the fear of losing their home. Early in the morning of 20 March 2019, bulldozers demolished Huda’s house. Her solar panel system, the only source of energy, was confiscated. This is how she lost her TV, the only pleasure available to her.

As the nearby Israeli settlement expanded, villagers lost access to large parts of their agricultural land. In 1991, a new Israeli outpost was built along the main road connecting the village to the town of Yatta. Since December 2000, the road has been off-limit for Palestinians for security reasons. This created a growing sense of isolation and having an immediate impact on all areas of life.

Masafer Yatta landscape seems austere and inhospitable. The dominant colour is yellow, as every object, animal or person is covered with dust. This impression dissipates as soon as I meet people who live here, many of them traditional cave dwellers. Tea is served, then coffee and fruit and local salty stone yoghurt, and then another round of tea. “I used to like it here,” Huda says “It is quiet. People don’t gossip.” The tea is very sweet, but the conversation grows bitter, as villagers talk about the hardship they face.