War in Cities: Sloviansk, Ukraine

When wars are fought in cities, it is civilians who bear the brunt. In this new series, we explore the devastating impact on people who have seen their streets and communities become the frontline.

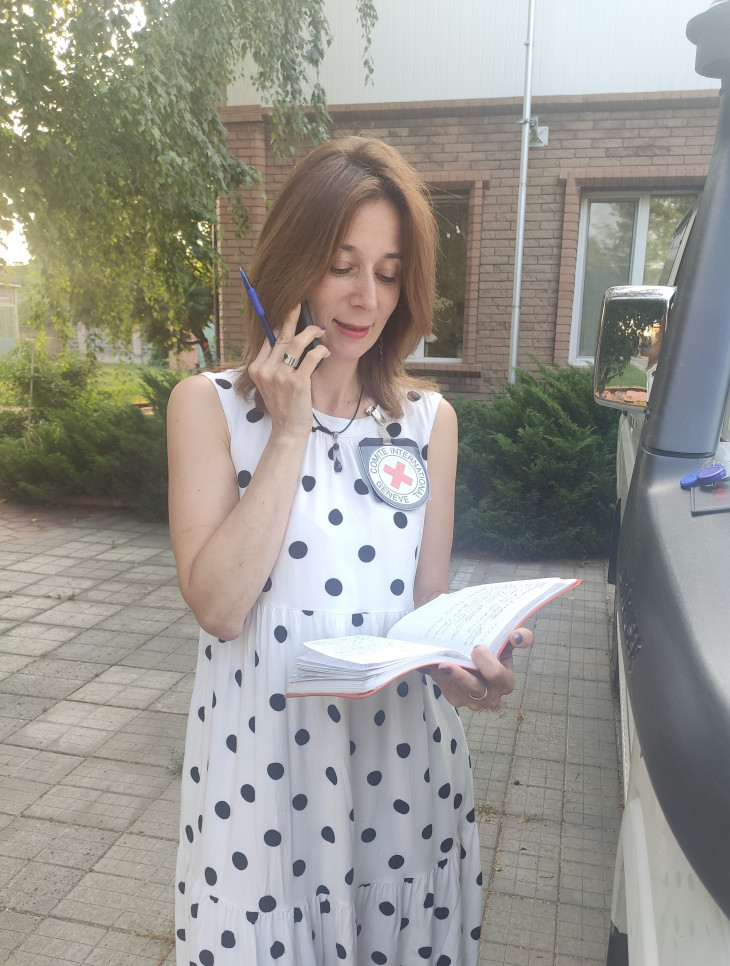

We spoke with Kateryna Mavrodi-Misiura, who works in Sloviansk, Ukraine, as a Protection Field Officer responsible for supporting families whose relatives have gone missing due to the conflict.

How long have you been in your role?

I joined the ICRC in 2014, and worked across multiple areas including health, economic support and field operations, both in state and non-state controlled areas all over Ukraine.

That experience gave me a solid understanding of the breadth of the ICRC's work, which has been so helpful in supporting the families of the missing because their needs, and our response to support them, is so varied.

In 2016 I began work on what we call the "missing file": our support for families whose loved ones have gone missing in conflict. I also work on Restoring Family Links (RFL) after families have lost touch because of conflict.

Can you give us a general profile of who goes missing, and who contacts the ICRC about a case?

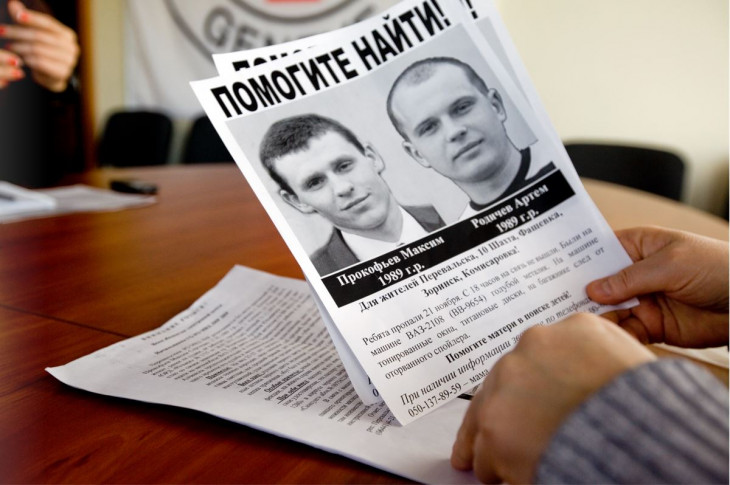

The majority of those missing in conflict in Ukraine are men of working age: 30-50 year olds, who were the main or sole earners of their households.

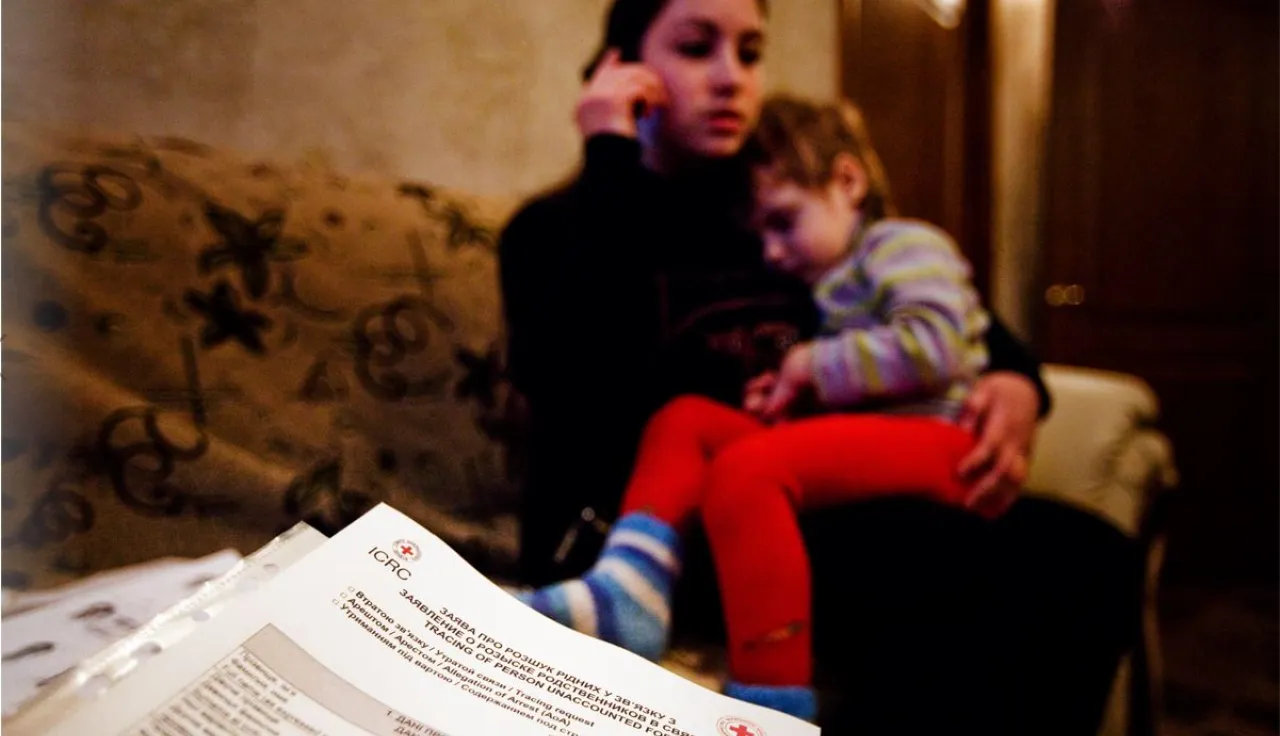

In turn, the vast majority of people I support are mothers and wives. They want to know where their sons are, where their husbands are.

They are experiencing psychological trauma from the conflict and from the anxiety of not knowing where their loved one is, day after day. They need help with basic needs. They need help with the legal and administrative aspects of what to do when someone goes missing.

Over 1,800 people have gone missing

The ICRC and the Ukrainian Red Cross have registered approximately 1800 cases of disappearances in relation to the conflict so far. Over 800 of those registered as a missing person are still unaccounted for.

Missing people are mostly males, either civilians or military. For this reason, most of the people who are looking for their missing relatives are females – usually their mothers and wives. But we also support fathers, daughters, sons, siblings, or even neighbours and close friends.

An overwhelming majority of disappearances occurred at the beginning of the conflict. Since then, people have been searching tirelessly for their missing relatives. The search is complex and expensive yet despite the long time, families have not given up searching for their loved ones.

So, what's the process and how do you support them?

Usually we receive a request from a family member.

We ask them to come to our offices, and then we talk.

Initially we talk about what happened. The case needs to be conflict-related for us to be able to take it on as this is our specific mandate.

Once we take a case, we have to be really clear with people about what we can and cannot do. Unfortunately, given the current situation in the conflict area(s) – we cannot carry out active searches in that area.

But, we are able to engage with the police force, the government, the health authorities (including hospitals and morgues), and we also engage with other organisations that could provide us with helpful information.

We explore whether they might be detained somewhere and unable to contact their loved ones. Does the government have any information on this individual that might help to locate their whereabouts? Has a body been recovered somewhere?

We also provide people with administrative and legal support to deal with all the paperwork involved with having a missing family member.

Yet our support goes much beyond that

For each case we take, we conduct a wider needs assessment. These families are suffering from the effects of conflict: houses destroyed, livelihoods ruined, and on top of that, a loved one has disappeared.

For some, we provide psychosocial support, to help them deal with loss, with the anguish and anxiety of not knowing the whereabouts of their husband, their father, their son.

For others, financial support is critical, because overnight the sole breadwinner is no longer there to support the family. Mothers and wives often ask us to help them find a missing person, and we find that they cannot even cover their basic needs, and are struggling just to get food on the table, to clothe their children. For some families, we offer small grants or and other financial support help them to create a sustainable source of income.

For many, it's also simply about having someone to talk to. Someone who will listen. Someone who cares. A conversation that proves their loved ones are not being forgotten.

One of the women we support, a lady in her 70s, had not one but both of her sons go missing during the conflict.

She lives alone, in a small house, and she is partially blind. She is just a lovely and engaging person. And very lonely.

I used to go and visit her at her home to follow up on the case, and after a while, it began to feel like I was going to see a family member. I know to her, it made a real difference.

There was another woman, whose house was destroyed during the shelling and so she had no permanent accommodation. We would go and sit in an ICRC car and talk. She said it really helped.

How long have these families been missing their loved ones?

At the moment, I am responsible for 74 cases in the local area. For the majority of those cases, the person went missing between 2014-2016. So, most people have been missing for five years or more.

After all those years, most families are beginning to lose real hope that their loved ones will ever come home and for many, that they might even find out one day where they died.

They are no longer crying in our offices or during our visits. But to me, it's just as heart-breaking. Sometimes it feels worse: it means a level of resignation, the loss of hope.

But what you can do is listen to them. Help where you can. It might seem small, but it's so important.

What's life like in Sloviansk at the moment?

Closer to the line of conflict, there are more of the visible scars of war: buildings that suffered from shelling, a feeling of unease as a results of conflict flare ups, restrictions at times.

However, in Sloviansk, though there is a large population of internally displaced persons (IDPs), like many other towns and cities not directly in the area of conflict, things look normal at first glance.

But the conflict and its impact is always present.

There is a lady that we support, she's around 60. Her son went missing in the conflict.

I see her almost every day, we are neighbours and walk our dogs in the afternoons. She lives alone with her dog.

For our neighbours, for those who don't know her well, and just see her and say hello - for the external observer, she is just a lady walking her dog.

They don't know how she feels inside.

The grief she has, it's not something that you can see or touch. It's not visual.

It's not like she was wounded in the conflict. But it's something that affected her soul. She carries that with her every day.

What about families that have been separated by the conflict?

Many of us are separated from loved ones. Some families have found themselves on the other side of the line of conflict to their families, including myself.

I live with my husband and daughter, but my parents live on the non-government controlled side, and it's not easy to cross between the two. It was always tricky but given current restrictions exacerbated by COVID-19, some checkpoints are closed.

For many people who used to do around a 70km journey, that has now turned into a journey of 1,000km. It's just not possible for many families to do that, with children, with elderly people, with low incomes, with no chance to take that much time off work.

It means my daughter can't see her grandparents. We can't go as a family to visit our relatives and friends. Some of the closest towns are 15-20km from each other, you can see the other side so clearly, you can see the windows of the houses. But you can't get there. You can't see those you love.

This separation is tough, but there is hope it will end one day. For those whose loved ones are missing, it is much worse.

This is why our work matters: we will do whatever we can to help.

Join our community to reduce the human cost

of urban warfare