Civilian population trapped in fear and anxiety

In Colombia, armed conflicts and violence continue to have a deep impact on the civilian population. Many civilians have been wounded, killed or gone missing; relatives have been separated from their loved ones; communities have been confined or displaced; young children and teenagers have got involved with armed groups; and individuals are suffering from psychological distress, fear, anxiety and permanent uncertainty.

In several parts of the country, people are enduring indescribable suffering that is exacerbated when armed actors fail to uphold IHL rules and humanitarian principles.

In 2022, our field teams recorded 400 suspected violations of IHL – some of them serious – and other humanitarian norms, of which more than half were homicides; threats; sexual violence; indiscriminate use of explosive weapons; recruitment, use and participation of children and teenagers in hostilities; arbitrary detention; and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

In relation to the conduct of hostilities, they recorded the failure of the parties to the conflicts to comply with the obligation to take precautionary measures to protect the civilian population and property.

The presence of armed actors near populated areas and the use of civilian objects with military purposes increased the pressure on communities and their fear of being caught in the crossfire or their community spaces being turned into military objectives.

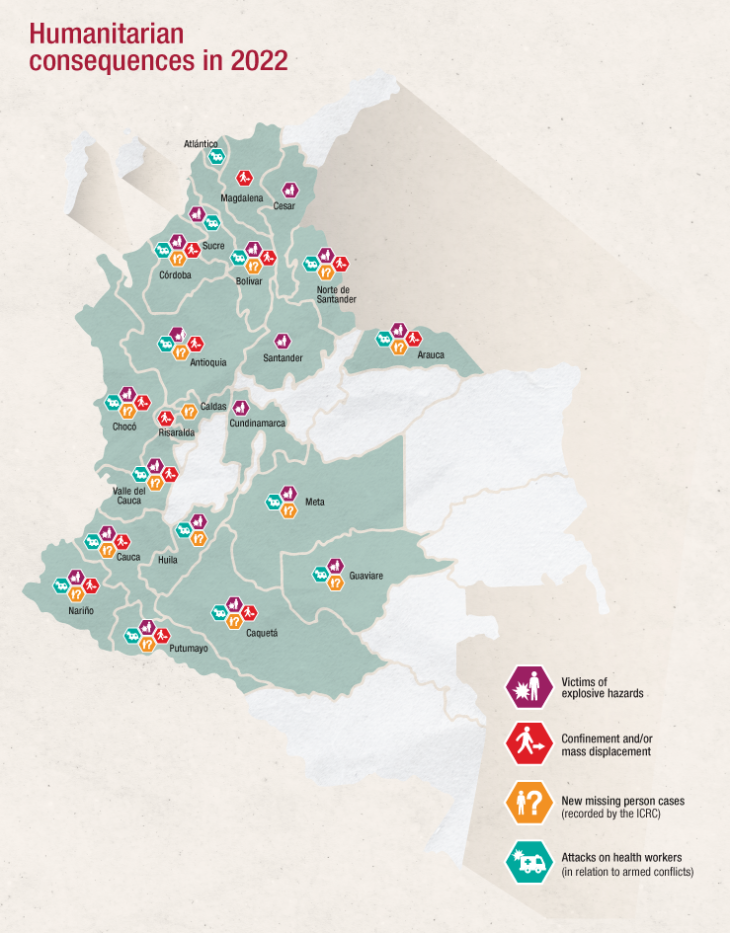

Other issues have added to this complex picture. Last year, we recorded 515 victims of explosive hazards, the highest figure in the last six years. This is further confirmation of a trend we have seen since 2018, where year on year the problem has grown worse and with it the scale of this human tragedy.

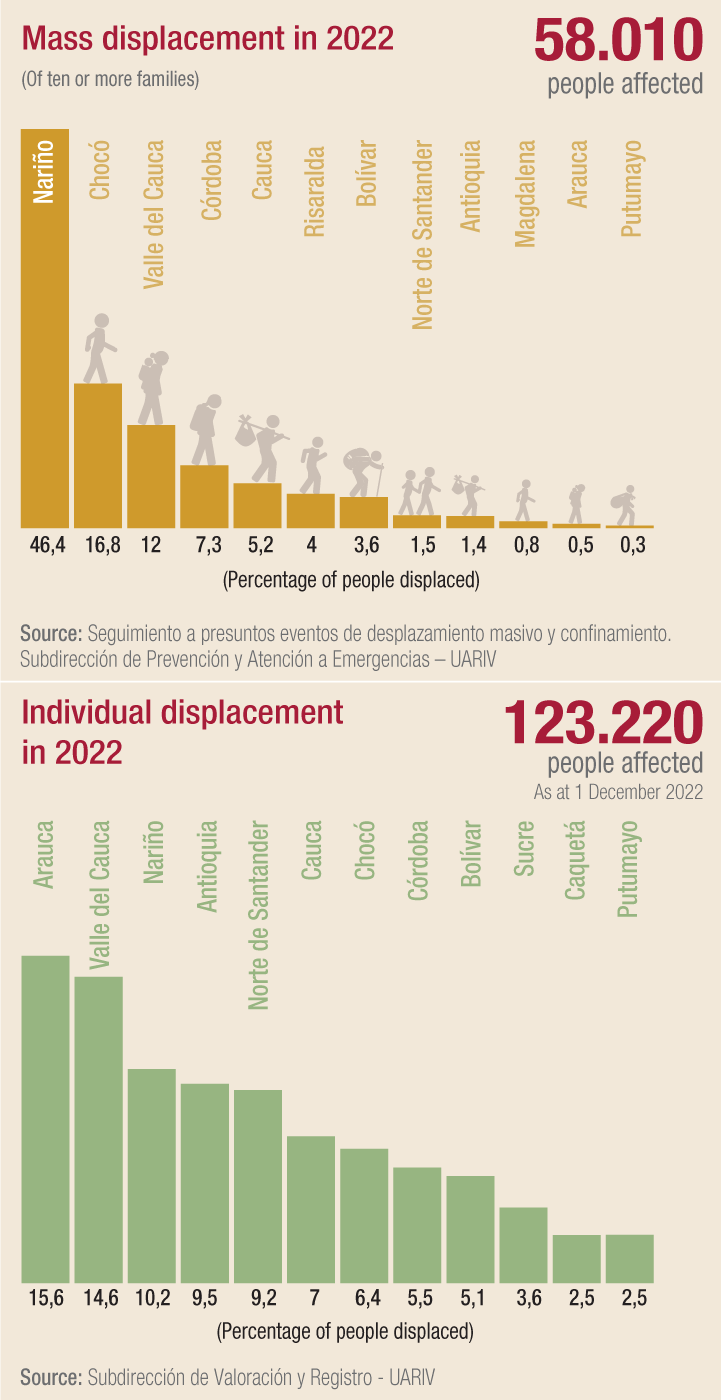

Last year, we recorded 348 cases of people who have gone missing in relation to the armed conflicts and violence since the Peace Agreement was signed, of which 209 went missing in 2022. These figures do not reflect the total number of people recorded missing nationwide, but they do show quite clearly that this issue is not confined to Colombia's past. According to official figures, last year there were at least 123,000 cases of individual displacement; mass displacement affected a further 58,000. All these people were forced to abandon their homes to save their lives.

Around 39,000 people were confined as a result of the upsurge in armed violence and the presence of explosive hazards in the areas where they lived: 64 percent of those confined identified as indigenous; 27 percent as Afro-Colombian.

SOURCE: Seguimiento a presuntos eventos de desplazamiento masivo y confinamiento. Subdirección de Prevención y Atención a Emergencias – UARIV

These figures indicate that the level of confinement and displacement have remained steady in certain departments, such as Nariño and Chocó. For the last four years, these two departments have seen the highest levels of mass displacement and confinement, respectively. Other areas have seen considerable changes.

One example is Arauca department, where confinement increased tenfold between 2021 and 2022 and individual displacement shot up from 763 people in 2021 to more than 19,000 people in 2022.

Attacks on health care continued last year; the most serious cases were recorded in the areas most affected by the armed conflicts and violence, e.g. health workers and patients were killed, received threats, suffered sexual violence or were subject to blackmail, and ambulances were held up at roadblocks. In some of these cases, those affected were too frightened to file an official complaint with the authorities.

Attention must be paid to the recruitment, use, and participation of children and teenagers in hostilities. We are concerned that armed state and non-state actors continue to involve children in the armed conflicts. This has profound consequences for them, such as being separated from their families; losing control over their lives; experiencing psychological issues; becoming victims of sexual violence; and being wounded, mutilated, or killed.

The lack of safe spaces, opportunities, and access to education, as well as the presence of weapon bearers near populated areas and the rise in their control over these areas, increases the vulnerability of children.

We remain deeply concerned by the sexual violence that continues to occur in the armed conflicts. These acts of violence are frequently used by weapon bearers as reprisals to generate fear or demonstrate power and to destroy the social fabric of the local population. There are many forms of sexual violence besides rape, such as sexual harassment or forced nudity, that can have devastating consequences for the victims, their families, and their communities.

However, most cases are never reported out of a fear of being attacked again or a feeling of guilt or shame. Obstacles remain that hinder victims of sexual violence from reporting cases and getting treatment within 72 hours of the assault, even in the event of a medical emergency where the victim's life is at stake.

All of the above demonstrates how complex the current situation is, and how the dynamics of the armed conflicts, the behaviour of weapon bearers and the consequences in humanitarian terms can vary widely from one place to another.

In 2022, fighting over territory intensified in several parts of the country. This exacerbated problems and increased risks for the civilian population, as communities not only had to face the direct consequences of the clashes (confinement, mass displacement, landmines, and unexploded ordnance, damage to property, etc.) but also faced pressure from armed actors who, on several occasions, accused them of belonging, helping or favouring one or another party to the conflict simply on account of living in that area and staying put in the midst of the fighting.

However, in other parts of the country clashes between government forces and armed groups went down for several months in the second half of the year, which reduced the direct effects of hostilities on civilians and provided a certain amount of relief. Despite this, the situation for communities in these areas continued to be complicated, since in some places weapon bearers remained in control and, with that, threats, violations and various types of abuse continued.

According to the ICRC's legal classification of conflicts, based on the criteria laid down in IHL, there are currently seven non-international armed conflicts in Colombia. Three of these are between the state and the following non-state armed groups (NSAG): the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Gaitanist Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AGC) and former FARC-EP currently not adhered to the Peace Agreement (former FARC-EP).

The other four conflicts are between the NSAG. One is between the ELN and the AGC, and the other three are between former FARC-EP and the Second Marquetalia, the Border Commandoes Bolivarian Army (CDF-EB) and the ELN respectively. This last conflict was classified recently as such following observation and analysis of hostilities between both groups and the generated humanitarian consequences over the last two years.

The changing dynamics of territorial control, the reconfiguration of non-state armed actors, the deterioration in the humanitarian situation and the weak presence of state institutions, which historically has existed in the areas most affected by the armed conflicts, show the multiple challenges facing humanitarians and the difficult living conditions and lack of security of the civilian population.

However, it is important to make clear that both the statisticsand the analysis contained in this report represent what we saw in 2022. Given how fast things vary in Colombia, this outlook may change.

Classification of armed conflicts

Why does the ICRC classify armed conflicts?

The ICRC classifies armed conflicts in order to fulfil its humanitarian mission, in accordance with the Geneva Conventions, their Additional Protocols and the Statutes of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. We work to promote respect for IHL by all parties, to protect the lives and dignity of victims of armed conflict and to provide them with assistance.

What criteria does the ICRC use to determine there is a non-international armed conflict?

The ICRC uses the criteria set out in IHL to determine whether a situation of violence should be classified as a non-international armed conflict. For this to happen, the armed groups involved must be organized to a sufficient degree and hostilities between parties must have reached a minimum level of intensity. The ICRC carries out a technical and objective analysis to determine whether these two criteria have been met on the basis of data gathered directly on the ground.

Are an armed group's motives relevant under IHL for classifying it as a party to a non-international armed conflict?

Under IHL, an armed group's motives – political, economic, religious, ethnic and so forth – are not requirements or criteria for determining whether an armed group is a party to a non-international armed conflict, or to whether IHL applies. Moreover, establishing that a non-international armed conflict exists and that IHL therefore applies does not confer any special status on the armed groups involved or their members. In this sense, IHL neither permits nor prevents a state from negotiating with armed groups.

More about 'Humanitarian Challenges 2023'

- "The importance of humanitarian action" Lorenzo Caraffi

- The constant threat of explosive hazards

- Unending uncertainty

- Health in the midst of conflict

- Overcrowding in temporary detention centres getting worse

- Releases: A reflection of our role as neutral intermediary

- Calls to action from ICRC to Colombia in 2023

- Colombia: Stories from the field