Unending uncertainty

To not know whether a loved one is dead or alive, what has happened to them or where they are was the painful reality for hundreds of Colombian families last year. People continue to go missing in relation to the armed conflicts and violence in the country, leaving scars that will take a long time to heal.

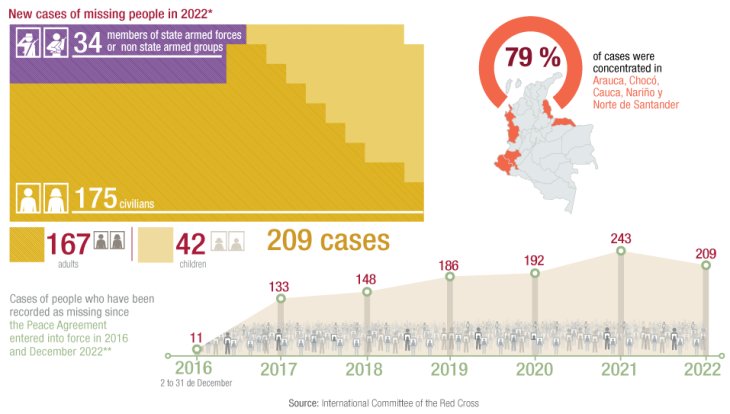

Our figures, which account for only a fraction of the cases, show the issue is still a live one in the country. Last year, we recorded 209 cases of people who had gone missing in relation to the armed conflicts and violence in 15 departments, of which Arauca, Chocó, Cauca, Nariño and Norte de Santander were the worst affected. These departments accounted for 79 percent of all our recorded cases. Since the Peace Agreement was signed in 2016, we have recorded 1,122 disappearances.

The control and pressure that weapon bearers exert not only shape the daily lives of communities but also determine communities' access to the institutions tasked with looking for their loved ones and meeting their needs. In some cases – out of fear of reprisals – families prefer to wait months or years before reporting a relative as missing.

How armed actors behave when dealing with wounded or injured people, as well as how they ensure these people do not lose touch with their families, can stop people from going missing in Colombia. In some parts of the country, one of the ways of exerting control over communities is not to allow them to recover the bodies of those who have died or inform anyone about the situation. In other cases, armed groups have informed various humanitarian organizations so that they can recover the bodies.

*These figures correspond to cases documented by the ICRC in areas where we are present and carrying out our humanitarian work. They are not, therefore, an exact reflection of the scale of the problem.

** **These figures may vary from publication to publication, as some disappearances are not reported during the same year in which they occurred. For example, we recorded 348 missing person cases in 2022,

of which only 209 occurred that year; the remainder occurred between December 2016 and December 2021.

Given the emotional upheaval that recovering the bodies of loved ones entails for thousands of families, we must insist on the need to strengthen state action to promote the dignified treatment of the dead, including in the most remote places. To achieve this, the state must provide the willpower and the necessary resources, especially to enable the proper functioning of the Unit for the Search for Missing Persons (UBPD). Likewise, weapon bearers in all parties must prevent people from going missing; this obligation is laid down in IHL.

All of the above is part of the bigger picture of disappearances that have taken place since 2016 and beforehand. The state must take the necessary measures for these disappearances to end, and to investigate the fate and whereabouts of those who have gone missing. They should promote the use of the Urgent Search Mechanism (MBU), which could help prevent others from going missing. This would mean raising awareness of the mechanism among civil servants and creating a system to follow up on the work carried out when institutions trigger the mechanism.

In addition, the relatives of missing people must have access to suitable mental-health care with the public health-care system. These are not simply statistics but broken dreams, destroyed families, hours of searching and waiting – sometimes for an answer that never comes – and, above all, the uncertainty and pain of not knowing what happened to a loved one or where they now are.

More about 'Humanitarian Challenges 2023'

- Civilian population trapped in fear and anxiety

- "The importance of humanitarian action" Lorenzo Caraffi

- The constant threat of explosive hazards

- Health in the midst of conflict

- Overcrowding in temporary detention centres getting worse

- Releases: A reflection of our role as neutral intermediary

- Calls to action from ICRC to Colombia in 2023

- Colombia: Stories from the field