Families of missing persons: Why education matters for their future

“Despite having experienced displacement, I always looked for means to continue schooling. Fortunately, when we stayed with relatives in Luzon, I was able to enroll and complete my junior high school. I worked as a cashier at my aunt’s store to somehow contribute. I completed my senior high school in Marawi and am now a second-year nursing student at a university there. Although we have been struggling financially, I will never give up on my education. My abie (father) always told me to finish my studies because it will be my key to a better future. The cash grant was truly helpful. I was able to buy my uniform and some nursing equipment with it. With classes being conducted virtually, the tablet is a huge help, too.”

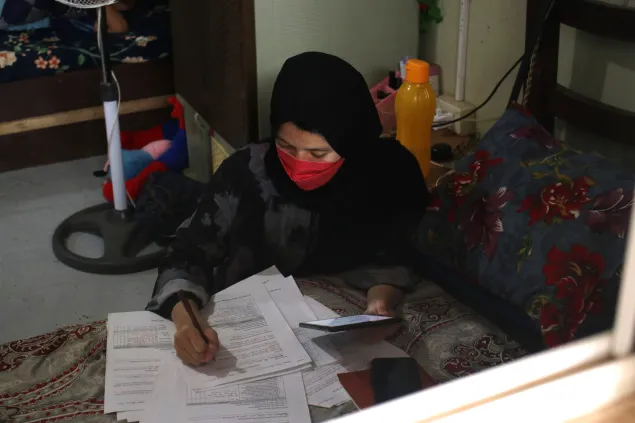

Hisham,16, son of missing person

“I was 12 when my father went missing. I did not understand it during the time. I started asking my mother about him after months of waiting for him to come home. I didn’t know how to process my emotions, and his disappearance haunts me until now. At times, I would see him in my dreams. I admired his skills – how he repaired home appliances and looked after our restaurants that I aspire to be an engineer. I’m now in 8th grade. I had to stop schooling for two years due to the displacement, and mainly because we did not have budget for my education. I am happy now that I am enrolled. Though modular learning is tougher than in-person classes, I still appreciate it. My mother bought me some school supplies and clothes with the ICRC’s cash grant. The restaurant she’s been running as part of ICRC’s microeconomic initiative also continues to prosper. I hope to have in-person classes soon.”

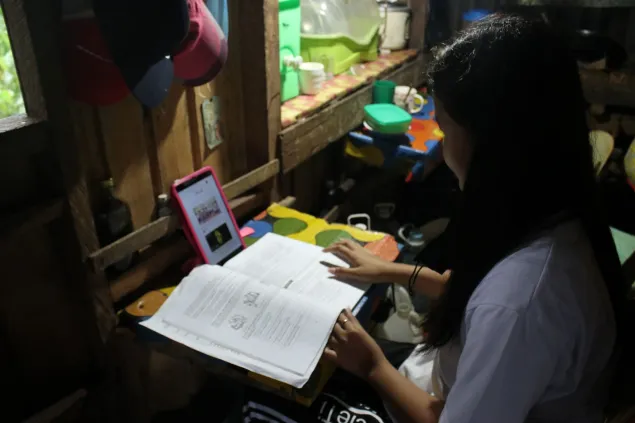

Mary Jane,13 and Joanne, 11, daughters of missing person

“I am now in 8th grade and my sister is in 5th grade. Things have vastly changed since our father’s disappearance. Our mom cried every night and I noticed how our lives have downsized. We didn’t have much, but it was better when papa was around. At times he helped us with our homework and took us to school. I feel sad every time I see my classmates being picked up by their fathers. Sometimes I wish I could call him through this tablet. I wish I could see him again and tell him how I’ve aced my classes. My sister always tells me how she would see him in her dreams. I do, too. We dedicate our education to him.

With the cash grant, we bought some clothes and school supplies. The tablet was a huge help, too. I can’t wait to start earning and help our mother.”

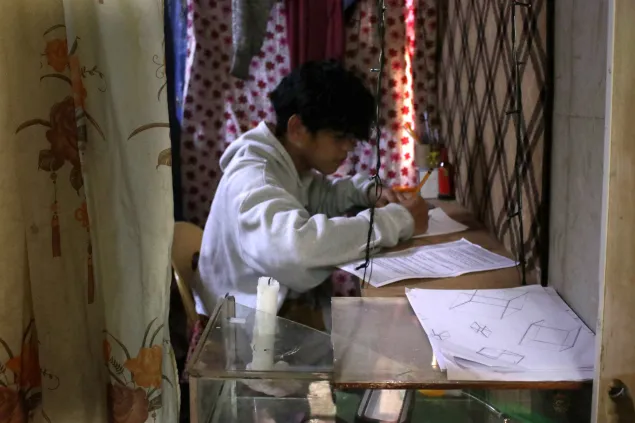

Jam, 14, daughter of missing person

“My father was a construction worker in Marawi. He provided my school allowance since my mother’s income from working went to our daily needs. With him no longer around, we struggled a lot. Dropping out of school was a tempting option, but I know I shouldn’t. I aspire to be a nurse and help my mother and lola (grandmother) who is severely ill. I’m currently in 9th grade. Thanks to the ICRC’s cash grant, I was able to buy my P.E. uniform, some school supplies, and paid for some school projects. I contact my cousins with it, too. To the other kids, never give up on your education.”

Hidaya was 16 when the Marawi crisis in May 2017 happened. She was in fourth-year high school and lived like the usual teenager: carefree but grounded, while aspiring to attain her dreams. But the five-month armed clashes robbed her of that normalcy. She was displaced while her parents were trapped in the fighting—never to be heard from again.

"The worst thing about losing your parents to ambiguity is not having closure. Just when you think you've fully recovered, the thought that they may still return comes to you at any moment, and you feel the emotion of losing them all over again," she said.

The emotional distress she endured at such a young age was made worse by the financial difficulties following her parents' disappearance. She became dependent on her older siblings who she understands have their own families to feed. "I worked as a cashier at my aunt's store to somehow contribute. It was completely different when my omie (mother) and abie (father) were around."

Hidaya's experience represents the reality of dozens more families who lost a loved one to the crisis. In several cases, it was the breadwinner who went missing, resulting in the role being assumed by relatives. Due to the financial burden, education becomes less prioritized and is often compromised.

The ICRC has been supporting families of missing persons (FoMs) in their various struggles since the aftermath of the crisis. The organization has implemented various programs to help these families economically and psychologically.

Recently, after assessing the added burden COVID-19 had on the education of families of missing persons like Hidaya, the ICRC saw the need to provide conditional cash grants and gadgets for their blended learning. Fifty FoMs received cash, tablet devicesand electronic load, between September and November. The project is aimed at supporting FoMs in their education, with the more vulnerable families–mostly those who lost their breadwinner to the conflict—being prioritized.

"Education is a humanitarian issue because it enables people to rebuild their lives with dignity. Humanitarian action helps people not only to survive but also to rebuild and improve their lives," said said Omar Hadjisocor, field officer of the ICRC's missing persons file.

"More importantly, access to education is a humanitarian issue because schools are important epicenters of community life and of humanitarian activity. Children have the opportunity to learn how to contribute to the protection and well-being of their own communities, especially in the face of conflict, violence and displacement," he said.

Hidaya and others shared how the cash grants and tablet devices have helped ease the burden and allow them to continue with their studies.

*All names were changed

If you wish to seek the ICRC's support in the search for your family members who went missing in the Marawi crisis,

you may text or call our hotline numbers:

Iligan-based: 0998-5798135 (Smart) and 0917-8645818 (Globe)

(Languages: Tagalog, Meranao and Bisaya)

Zamboanga-based: 0947-9703578 (Smart) and 0956-6923181 (Globe)

(Languages: Tagalog and Tausug)