The human cost of armed conflicts in Colombia

The civilian population continues to bear the brunt of the war. We wish that the figures we report here for humanitarian consequences belonged to the distant past. However, these figures reflect the daily life of thousands of families, particularly peasants, indige- nous people and afro colombian people.

Throughout 2023, we supported communities who had been displaced and who, scared for their lives, took the only way out they had: leaving their homes and losing everything. We also provided support to people who were determined to start or continue the search for their relatives reported missing. We helped those who, in the midst of uncertainty, were confined to their communities with limited access to basic resources.

There were no significant improvements to the humanitarian situation that communities face in the regions where we worked. Throughout the year, our field teams documented 444 alleged violations of IHL and other humanitarian norms by state and non-state armed groups. These violations included threats; sexual violence; recruitment, use and direct participation of children and adolescents in hostilities; homicides; use of explosive devices with indiscriminate effects; cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment; and arbitrary deprivation of liberty, among other violations.

We also found non-compliance by the parties to the conflict in the way they went about hostilities. In most cases, this non-compliance took the form of a failure to protect the civilian population and their property from the effects of these hostilities.

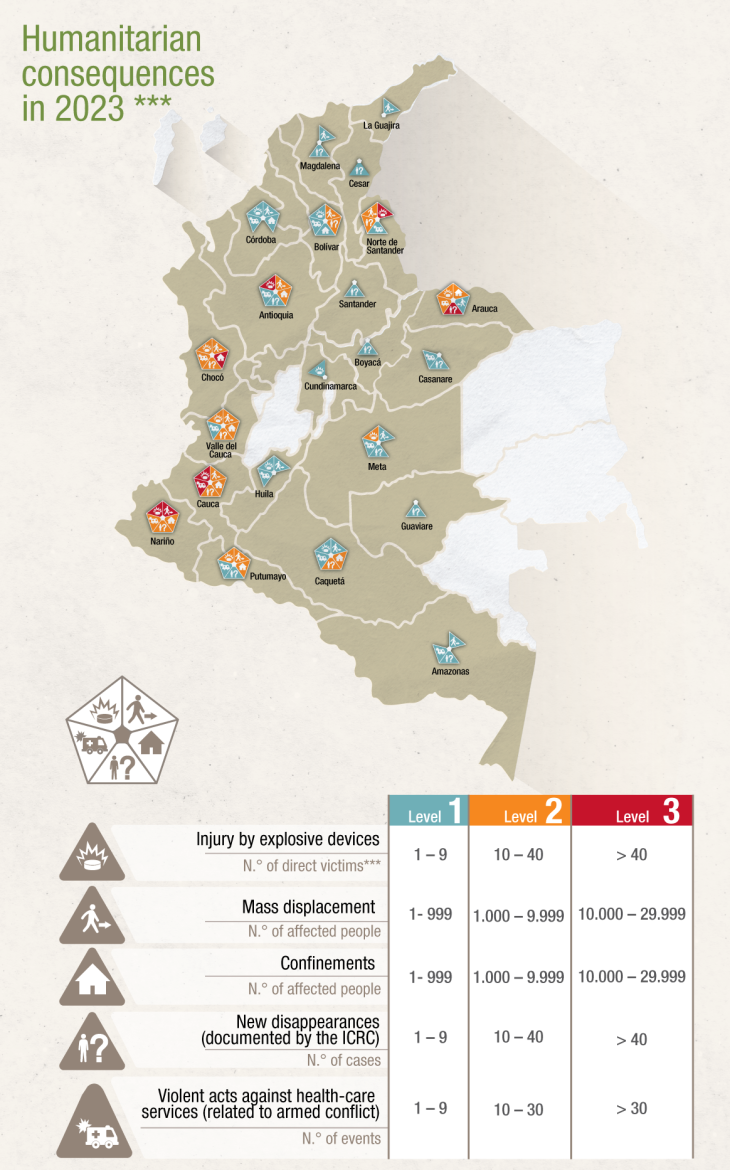

According to official figures, 145,049 individuals were displaced, an increase of 18 per cent nationwide com- pared with 2022. In some territories the increase was even higher. In the department of Bolívar, the number almost doubled, with a 94 per cent increase compared with the previous year. In Cauca, the figure rose by 53 per cent. This issue tends to be less visible than other humanitarian consequences, but is nonetheless alarming, as families often abandon their homes for long periods of time or may even never return.

A further 50,236 people were displaced en masse, fracturing the social and cultural practices of the affected populations. For the fifth consecutive year, Nariño was the department with the highest number of people affected, accounting for 52 per cent of all displaced people.

Analysis of these figures shows that, at the national level, there was a 13 per cent decrease in this phenomenon compared with 2022. However, the problem spread to other departments such as Amazonas, Huila, Meta and La Guajira, which did not register mass displacement in 2022, but in 2023 saw more than 1,000 people affected.

In addition, in some departments there was a substantial increase, such as in Putumayo, which went from 169 people displaced en masse during 2022 to 2,009 in 2023, an increase of more than 1,000 per cent.

Displaced people face economic hardship due to the loss of their livelihoods. Particularly vulnerable com- munities also face the risk of re-victimization. The consequences of displacement also have a direct effect on mental health.

Similarly, territorial disputes between armed actors and the presence of explosive devices led to the confinement of 47,013 people, a 19 per cent increase at the national level compared with 2022. The situation continues to be critical in the department of Chocó, which accounted for 44 per cent of the confined population. In other territo- ries there was also a greater increase than the national percentage. For example, Antioquia went from 110 people confined in 2022 to 1,224 in 2023 and Cauca went from 1,615 people confined in 2022 to 4,000 in 2023. These situations generate uncertainty, fear and anxiety in the communities and hinder their access to essential resources and services such as food, water, education and medical care.

In Arauca and Sur de Bolívar departments, communities are caught in the middle of the confrontations. It is essential that the armed actors respect the principles of IHL in order to limit the consequences for the civilian population and thus avoid at all costs displacement, confinement, disappearances, threats and dispossession.

On another front, in 2023 we recorded 380 direct victims of different types of explosive devices. The number of victims of controlled detonation explosive devices decreased compared with 2022, possibly owing to the ceasefires agreed between armed groups and the government of Colombia. However, this decrease does not imply that the threat from the presence of these devices has been reduced, but rather that there is a change in their use that has a different impact on the populations.

Last year we also documented 222 cases of disappearance directly linked to armed conflicts and violence that occurred during 2023. This figure shows that disappearances continue to affect families and entire communities, with people tormented by the uncertainty of not knowing where their loved ones are or what has happened to them.

Increased violence against health-care services was also reported. Incidents include various armed actors entering medical facilities and units, putting arbitrary restrictions on the movement of medical personnel and transport, and using them by force. The intensification of this type of violence, in terms of murders, threats and deprivation of liberty among medical personnel, is alarming.

We were also concerned to note that during 2023, children and adolescents continued to be associated with armed actors. This situation requires particular attention. In many cases, these minors have been separated from their families, which has led to psychological or psychosocial breakdown and suffering, in turn affecting their dignity and full development. Not to mention the direct threat to their lives.

Sexual violence in the context of armed conflicts in Colombia also continues. Last year we documented 50 cases, which reflect only a small fraction of the huge number of victims and survivors of this type of violence. Similarly to other humanitarian disasters, although sometimes much more pronounced, sexual violence is intended to intimidate, terrorize, punish and control territories. Women and girls have been the most vulnerable to and affected by sexual violence. However, most victims and survivors do not report their abuse for fear of stigmatization, lack of guarantees for their safety and difficulties in accessing justice and reintegrating into their communities. Sexual violence has devastating consequences for victims and survivors, as well as for their families and communities, with effects on physical and mental health, as well as social and economic effects.

Confrontations between the government and armed groups decreased in 2023, while disputes between non-state armed actors intensified. This meant continued suffering for the communities that were stuck in the middle of the confrontations.

According to our current legal classification, based on IHL criteria, there are currently eight non-international armed conflicts in Colombia. Three of them are between the government of Colombia and the following armed actors, respectively: the National Liberation Army (ELN), the Gaitanist Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AGC) and former FARC-EP currently not adhered to the Peace Agreement (former FARC-EP).

The other five conflicts are between non-state armed actors: the first is between the ELN and the AGC and the remaining four are between the former FARC-EP, and 1) the Second Marquetalia, 2) the Border Com- mandos – Bolivarian Army, 3) the ELN and 4) the AGC. The ICRC recently classified this latest armed conflicts after two years observing and analysing the hostilities between the two armed actors and the humanitarian consequences.

Armed conflicts persist in Colombia, and their humanitarian impact has not been substantially reduced. Testimonies and figures on displacement; confine- ment; sexual violence; recruitment, use and direct participation of children and adolescents in hostilities; the presence of explosive devices and the impact they have on the civilian population; as well as violence against health-care services all highlight the need for all armed actors to respect IHL.

The reorganization of non-state armed actors and the humanitarian consequences affecting the civilian population, coupled with the historical institutional weakness in Colombia's most remote areas, mean there is still a long road to be travelled to mitigate the suffering caused by armed conflicts and violence. However, even in this scenario, communities continue to weave stories of resilience.

Classification of armed conflicts

Why does the ICRC classify armed conflicts?

The ICRC classifies armed conflicts solely to fulfil its humanitarian mandate. This includes carrying out its functions under the Geneva Conventions, their Additional Protocols and the Statutes of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, promoting respect for IHL and ensuring protection and support for the victims of these conflicts.

On what criteria does the ICRC base its classification of a non-international armed conflicts?

The ICRC relies on IHL, which establishes two criteria for a situation of violence to be classified as a non-international armed conflicts: the armed actors must show a minimum degree of organization and hostilities between the parties must reach a minimum level of intensity. To qualify, both criteria must be met. The ICRC technically and objectively analyses whether these two criteria are met on the basis of infor- mation collected directly in the territories.

Is an armed actors motivation for legal classification relevant to IHL?

For IHL, the motivation of an armed actors – whether political, economic, religious, ethnic or other – is not a requirement or element of analysis for being a party to a non-international armed conflicts or for the application of IHL. Moreover, the application of IHL to a non-international armed conflict does not grant a special status to armed actors or their members. In this sense, IHL does not permit or prevent a state from negotiating with armed actors.

Read 'Humanitarian Report 2024'

- The human cost of armed conflicts in Colombia

- Wars have limits that must be respected: Lorenzo Caraffi

- The invisible consequences of explosive devices

- Lost in a maze: the footprints left behind

- Worrying increase in violence against health in Colombia

- Return to freedom: 44 years of neutral intermediation

- Rights do not end behind bars

- Communities tell their stories

- Calls to action