The ICRC in World War Two: The Holocaust

27 January is the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz in 1945. For the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), it also marks a failure, the failure to help and protect the millions of people who were exterminated in the death camps. The ICRC has publicly expressed its regret regarding its impotence and the mistakes it made in dealing with Nazi persecution and genocide.

Under Hitler's regime, Jews were deprived of all their rights and dispossessed of their property, packed into overcrowded ghettos, forced to wear a yellow star and subjected to countless forms of humiliation and brutality, to deportation and massacres. During the war, the number of roundups increased and Jews were systematically deported to concentration and extermination camps, cut off completely from the outside world.

In December 1939, the president of the ICRC approached the German Red Cross to arrange for the ICRC delegates to visit the Jews from Vienna who had been deported to Poland. He met with a refusal, as the German authorities did not under any circumstances want to enter into a discussion on the fate of these people.

From then on, the ICRC opted for a strategy of no longer addressing the question of Jews directly – it did so only in general approaches concerning the victims of mass arrests or deportation, and then it made no reference to their religious affiliation or racial origins, although it was clear that the people in question were, for the most part, Jews.

On 29 April 1942, the German Red Cross informed the ICRC that it would not communicate any information on "non-Aryan" detainees, and asked it to refrain from asking questions about them.

Information about the persecution inflicted on Jews did, however, filter out of Germany and the German-occupied countries, to reach the Allied governments, and some of this information also became known to the ICRC.

In the summer of 1942, the ICRC debated whether to launch a general appeal on violations of international humanitarian law. It prepared a draft, but decided in the end not to issue the appeal, believing that it would not achieve the desired results. The ICRC therefore continued with its bilateral approaches.

Food parcels

A year later, the ICRC obtained authorization from the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs to send food parcels to internees in the concentration camps whose whereabouts it knew of. It had details concerning about 50 deportees, to each of whom it sent a parcel, and during the summer it received acknowledgements of receipt countersigned by the addressees. The ICRC subsequently managed to find out where other deportees were interned and it expanded its parcel-sending operation. By 1 March 1945, the ICRC had details on about 56,000 deportees, and by the end of the hostilities, 105,000. From the summer of 1944 onwards, the organization supplemented its individual parcels with collective shipments. In total, up to May 1945 it sent over 122,000 parcels to the concentration camps. But this operation did not succeed in reaching those deportees who were subjected to the harshest regime, nor did it give captives any protection from torture or massacres. The ICRC thus continued its approaches to the German authorities, in order to visit the concentration camps. These approaches met with a categorical refusal.

In October 1943, the ICRC sent a delegate named Jean de Bavier to Hungary. On 17 May 1944, Friedrich Born arrived to take his place. Powerless to prevent it, they witnessed the wave of deportations to Auschwitz of almost all the Jews living in the provinces, which was organized by the SS between 15 May and 7 July 1944.

The work of Friedrich Born

In July 1944, Born obtained authorization from the Hungarian government to provide the Jews in Budapest with certificates showing that they were in possession of immigration papers issued by Latin American countries. These certificates did not enable the Budapest Jews to leave Hungary, which was surrounded by territories under the control of the Reich, but they did afford them a certain amount of protection.

In addition, Born set up around 60 children's homes which took in between 7,000 and 8,000 Jewish children, including many orphans. He placed under his protection all the hospitals, shelters and community kitchens that belonged to the Jewish community in Budapest. To do this, he took on a staff of some 3,000 volunteers, mostly Jews, and gave them documents legitimizing their status.

These measures were generally respected up until the time the regent, Admiral Miklós Horthy, was overthrown on 15 October 1944 by the Arrow Cross Party, which, in a matter of days, deported over 50,000 Jews from the capital, sending them in the direction of the German border.

Born, unable to prevent this deportation, distributed some relief supplies to the deportees, who had been deprived of everything. He did, however, prevent the departure of the last convoys, which consisted of about 7,500 people (read more on Friedrich Born).

Other activities in Europe

In Bucharest, two ICRC delegates, Charles Kolb and Vladimir de Steiger, tried, among other things, to make various proposals that would have enabled Jews to emigrate to Turkey and, from there, to Palestine or Latin American countries. With the support of Jewish organizations, the delegates submitted these proposals and made different types of representations to the authorities, all of which came to nothing, as it was impossible to obtain the necessary permission. Nevertheless, the ICRC delegates did manage to save some Jews from being deported.

On 23 June 1944, an ICRC delegate, Dr. Maurice Rossel, went to Theresienstadt. His visit was carefully orchestrated. He walked through the ghetto under the escort of SS officers, but he did not have the opportunity to talk with the Jewish people there, nor to get inside the fortress. Two representatives of the Danish government also took part in the visit.

On 27 September 1944, Dr Rossel went to Auschwitz. There he spoke to the commander of the camp, but he was not authorized to go inside it.

Inside Dachau

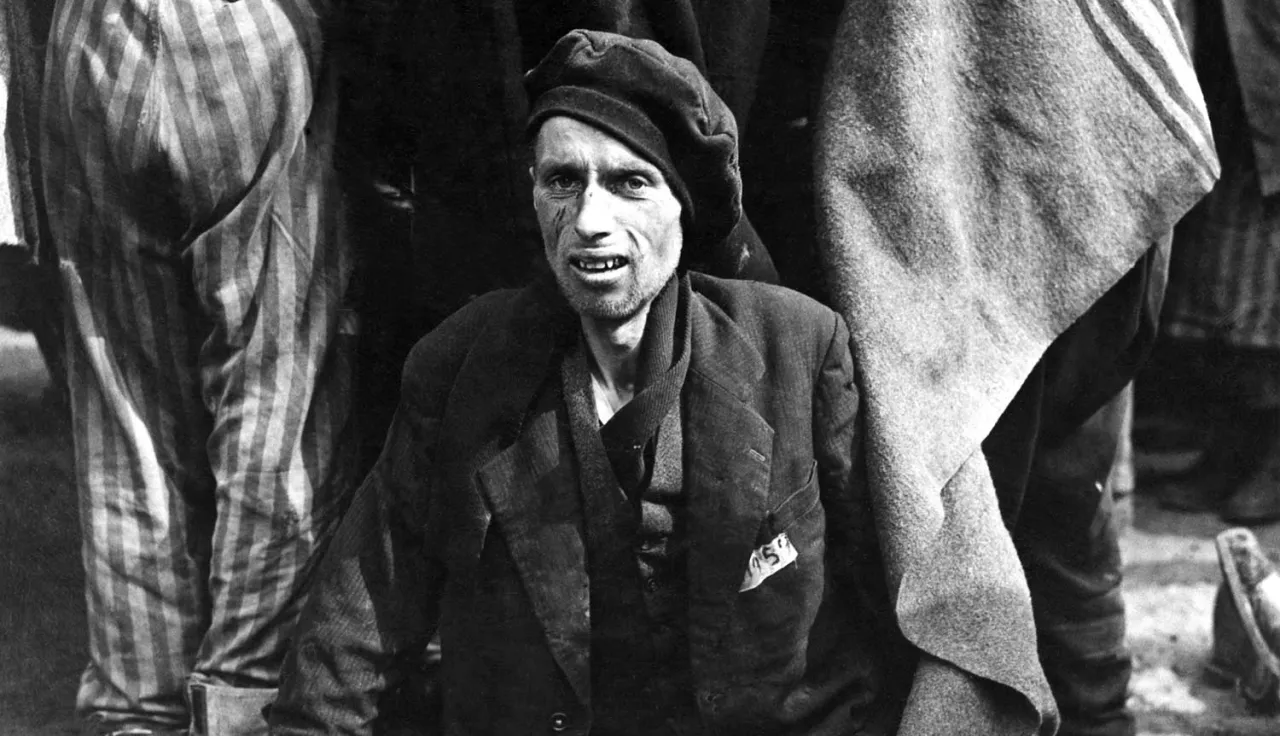

In the last days of the war, ICRC delegates were able for the first time to go inside the camps at Turckheim, Dachau and Mauthausen. They succeeded in preventing last-minute executions, and negotiated the surrender of the camps on the arrival of the Allied forces. The ICRC delegate at Mauthausen, Louis Haefliger, managed to get an order revoked, thereby preventing the underground aviation factory at Gusen (which was part of the camp) from being blown up, together with the 40,000 or so detainees who were in it.

The ICRC delegates were not able to prevent the evacuation of the camps at Oranienburg or Ravensbruck, which took place under appalling conditions. The delegates could only try to give out food supplies to the deportees on the roadside.

Apart from the work of Born in Hungary and a few sporadic instances elsewhere, the ICRC's efforts to assist Jews and other groups of civilians persecuted during the Second World War were a failure.

By taking part in the 1995 ceremony to commemorate the liberation of the Auschwitz camp, the President of the International Committee of the Red Cross, Cornelio Sommaruga, sought to show that the organization was fully aware of the gravity of the Holocaust and the need to keep the memory of it alive, so as to prevent any repetition of it. He paid tribute to all those who had suffered or lost their lives during the war and publicly regretted the past mistakes and shortcomings of the Red Cross with regard to the victims of the concentration camps.

Read also:

- Dialogue with the past: The ICRC and the Nazi death camps - François Bugnion, the ICRC's director for International Law and Cooperation within the Movement, reflects* on the organization's failure to react vigorously to the persecution of Jews by the Third Reich.

- The Nazi genocide and other persecutions

- Commemorating the liberation of Auschwitz - 27 January 2005 - Auschwitz, which represents the greatest failure in the ICRC's history, remains a powerful symbol of the horrors committed by the Hitler regime and serves to remind humanity that it must act in the face of future threats of genocide.

- ICRC in WW II: bibliography