Thirty-six years after the end of the conflict between Argentina and the United Kingdom, an ICRC forensic team went to the Falkland/Malvinas Islands to collect DNA samples from the remains of 122 unidentified soldiers. They hoped to give the Argentine soldiers back their names and help family members to cope with their grief. In March 2018, more than 200 family members visited Darwin cemetery to pay their respects.

Falkland/Malvinas Islands: Giving back the dead their names

It is the year 1983. British soldiers perform a gun salute in honour of the Argentine soldiers buried in Darwin cemetery. When the war ended in June 1982, some of the fallen Argentine soldiers were buried in temporary graves close to where they died. A second proper burial was then undertaken under the command of British Army Colonel Geoffrey Cardozo.

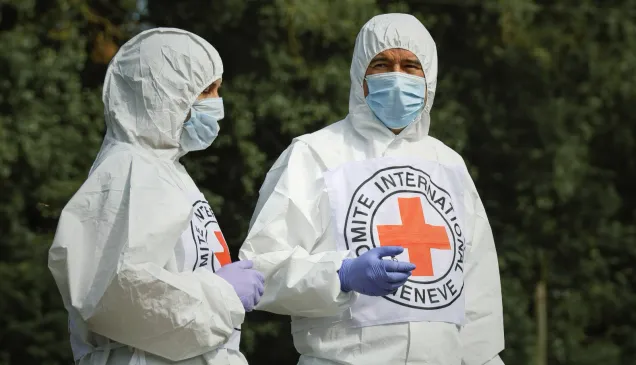

In June 2017, Father John Wisdom blessed the site and ICRC forensic specialists before the start of the exhumations. Fourteen experts came from Argentina, Australia, Chile, Mexico, Spain and the United Kingdom.

After carefully pulling out the crosses and tombstones, forensic logicians used a small excavator to remove the earth above the coffins, and then small shovels and trowels to delicately unearth the bodies, wrapped in white bags. After 35 years in damp soil, the wood of the coffins had totally disintegrated.

Luis Fondebrider (centre) is the president of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team. In 1997, he headed the forensic team commissioned by the Cuban government to retrieve the body of Che Guevara in Vallegrande, Bolivia. He regularly collaborates with the ICRC.

The forensic work continues on the autopsy table where the mortal remains are analysed in-depth. In addition to documenting findings which will assist in the identification (e.g.gender, age, stature, dental traits), the forensic specialists collected small samples of skeletal material (teeth and bones) for later DNA testing by genetics laboratories.

Forensic specialists find a military ID card on the first body exhumed. They see it as a positive sign. DNA testing will probably confirm the identity of the deceased.

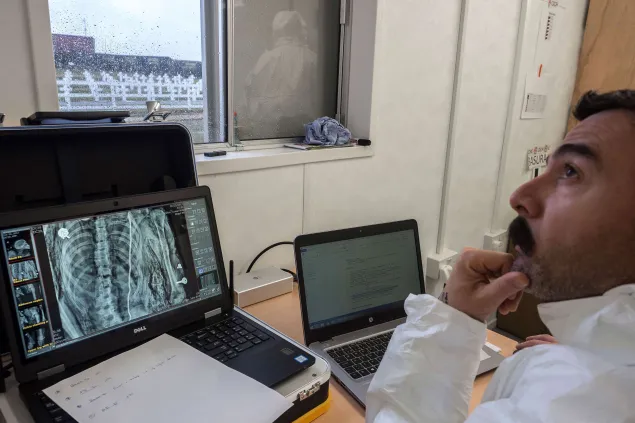

In the forensic laboratory, all the bodies are X-rayed. The forensic radiologist, together with the pathologists, anthropologist and odontologist, searched for clues, such as old fractured bones or specific dental work, that could help match the bodies to one of the medical files handed over to the ICRC team by the authorities or families of the deceased.

Various objects found on one of the bodies: matches, batteries, Argentinian banknotes, a plastic rosary... In this case, they didn't help with the identification.

The specialists had to complete the forensic reports and enter all the data collected for each case within 24 hours of examining each body, which was not an easy task. “But,” said Morris Tidball-Binz (right), “It was worth the effort. Everyone has the right to be identified after death, including those who die on the battlefield.”

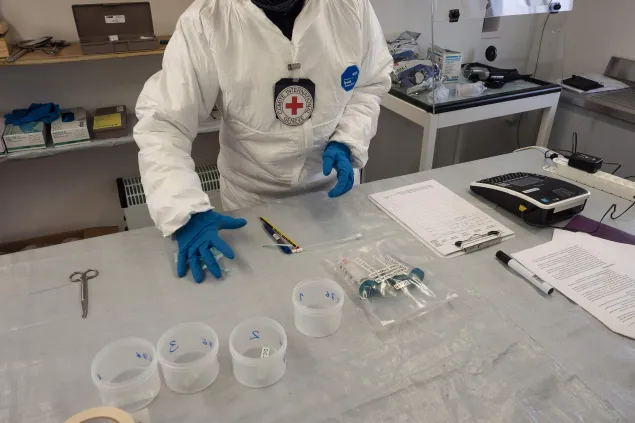

Forensic pathologist Mercedes Salado Puerto has just sealed DNA samples into a plastic pouch, which bears her signature and that of Morris Tidball-Binz, the head of the project. Their signatures on the sealed pouch served as a guarantee of the chain of custody until the samples arrived at the forensic genetics laboratories in Argentina, Spain and the United Kingdom. In 2013, Mercedes worked on the exhumation of Chilean poet Pablo Neruda.

Immediately after the forensic examination, the bodies were placed in a new coffin and reburied in the same place where they had rested for the past 36 years. The remains and their resting places were treated with the utmost care and dignity throughout the operation.

On the road to the main town of the Falkland/Malvinas Islands, Port Stanley/Puerto Argentino. Over the seven weeks' duration of the project, the challenging working environment was compounded by harsh weather conditions, including freezing temperatures, strong winds and snow storms. But in the end, 90 Argentinian soldiers were identified. In the coming years, more cases could be solved as other families join the identification process.

The 1982 war between Argentina and the United Kingdom was brief but a source of intense pain for many families.

Over 900 soldiers died on both sides, with three civilians killed. Some disappeared in the fury of the battle or were laid to rest without being identified. More than 200 Argentine soldiers – 122 of them without any names – were buried in Darwin cemetery, at the heart of the Falkland/Malvinas Islands.

In 2017, an ICRC forensic team was able to identify 90 of them, to the relief of their surviving family members.

In March 2018, more than 200 of them visited Darwin cemetery to pay their respects.