Not only on Mental Health Day: why mental health matters in conflict

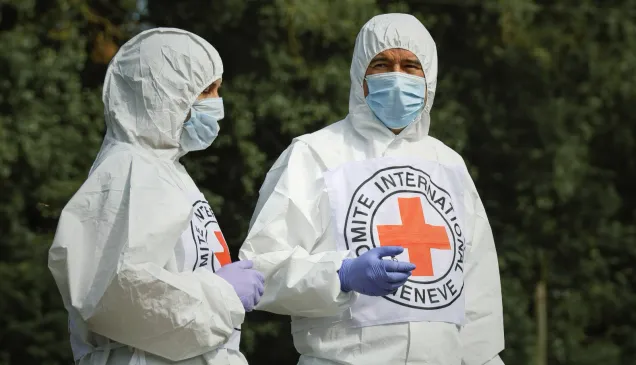

Marcello Queiroz is ICRC's regional specialist in mental health across the Middle East. On World Mental Health Day, we asked him what the picture is like for mental health across the region.

Why does mental health matter in conflict?

The evidence says more than one person in five - that's 20 per cent of people - that live in a conflict area have some form of mental health condition.

So, in a conflict-affected area we're talking about mental health issues being three times more than among the general population.

And it's not just the prevalence of mental health issues, it's also the lack of access to health care and mental health care in particular - it's harder in conflict affected areas than for the general population.

And it's not just the prevalence of mental health issues, it's also the lack of access to health care and mental health care in particular - it's harder in conflict affected areas than for the general population.

We're talking about people who have witnessed traumatic events, are survivors of sexual violence or families of missing people. People who have seen loved ones, friends, neighbours lose their lives in war or are forced to leave their homes and communities.

This is what makes mental health a priority for the ICRC response and humanitarian response in general.

We know that mental health support can be life-saving in times of war and violence, because when you don't address these needs, they can have far reaching and long-term consequences.

COVID-19 still looms large across the region

I think globally we are still dealing with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mental health was hugely affected by the social restrictions imposed during the pandemic, as well as the long-term economic impact.

As we all know, long periods of lockdown are draining and can affect our mental health.

One lady who phoned our mental health support hotline in Gaza explained this very well - on top of the mental health consequences of being infected, there is the psychological distress of being in quarantine - for almost 100 days in her case. It's hard to cope with that.

This woman is fighting cancer, #COVID19 and depression.

Not all scars are visible.

We support the #COVID19 hotline in #Gaza which provides thousands of people with psychological aid. pic.twitter.com/gL5kmJYHf7— ICRC in Israel & OT (@ICRC_ilot) October 27, 2020

Who are the most vulnerable?

People who live in remote communities, people who live in the shadow of long-running conflicts, or the millions of people who are currently refugees. The Syrian refugees for example, in Lebanon, Jordan.

We care about people who are already in a very vulnerable situation and now also have to deal with COVID-19. To be honest, if you asked them, they would tell you that COVID-19 is not their highest concern.

The people the ICRC serves are already caught up in conflict. There are people, deprived of liberty as detainees who do not have regular access to their families and don't necessarily have access to mental health care. COVID-19 makes it even more challenging to support these people.

It has also hit governments in terms of health budgets, as well as the capacity of all humanitarian organisations to provide support, because of movement restrictions and our ability to support those people.

A better understanding of mental health

I think the pandemic has made all of us more aware of the importance of mental health.

Even for us as professionals, we can think we're protected because we're professionals; we're here to provide support to others. But I think all of us, in different ways experience negative impacts.

The impact of COVID-19 on our mental health - even working from comfortable homes - has given us some experience of what it means to be confined and unable to see our loved ones, to be restricted in our movements and to try to find meaning...to find hope.

I think this pandemic has the power to sensitise more people to the importance of mental health and especially to draw attention to the inequality of access to support.

Hopes for the future

My hope is that we can learn from the challenge that we're facing on providing mental health during COVID-19 to scale up the services for mental health globally. To ensure that mental health care is accessible for all.

When you look at the numbers again, you see that in the low to middle income countries, three in four people that have have a mental health condition don't have access to proper care. That has to change.

When you see that, for example, in average only two per cent of national health budgets are dedicated to mental health, it's clear we need to be scaling up services.

And for me personally my hope is that people in conflict affected areas are considered the priority for mental health care.

It's vital that mental health care is available not only where it's convenient, but where people need it most.

Find out more about our lifesaving work on mental health.