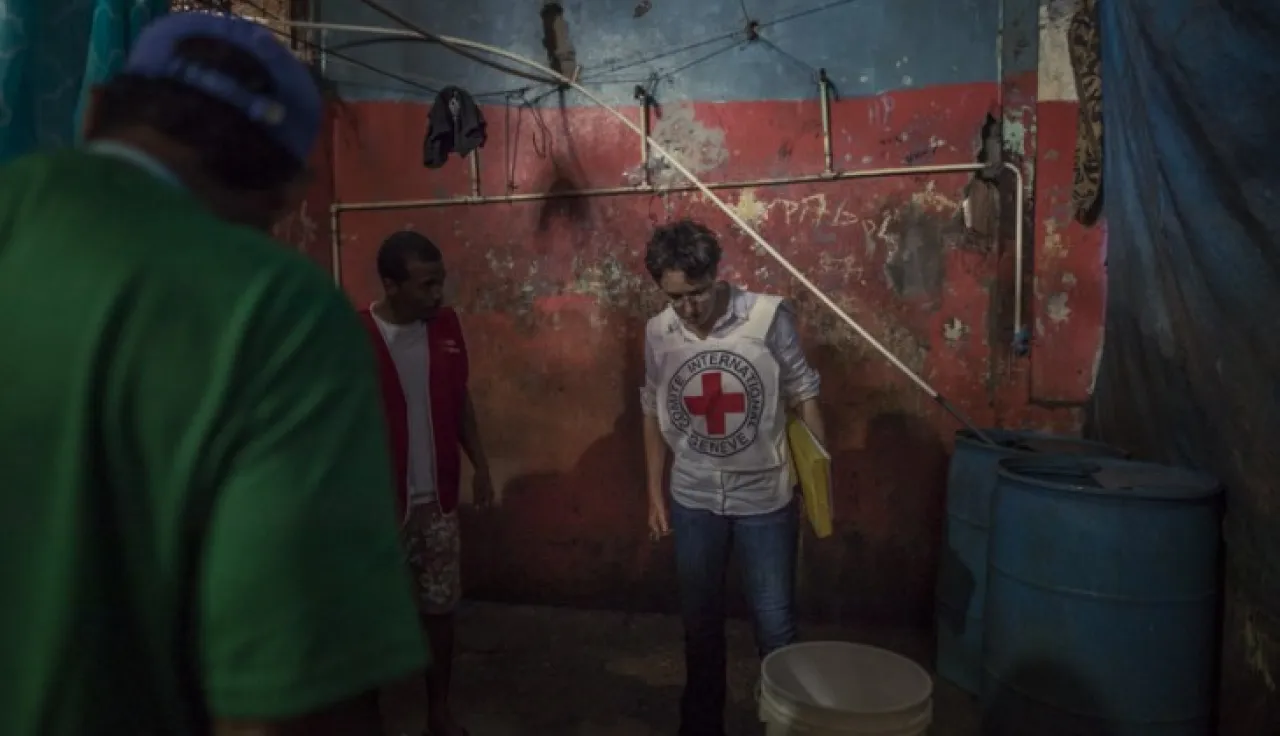

In close collaboration with the Panamanian Red Cross, we work to provide a humanitarian response to migrants after their journey through the Darien region. Learn more in our 2024 activity report.

Panama: Humanitarian Report 2024

The Darien Gap: a jungle of hope, pain and uncertainty

Alexandre Le Breton

Head of ICRC´s mission in Panama

Nobody is ready to cross the Darien Gap. Nobody is ready to trek through the jungle for days, facing unavoidable dangers and finding dead bodies along the way. Nobody is ready to cross rivers with the very real fear of losing their children. Nobody.

Our work in numbers

Joel, a Venezuelan migrant. Village of Bajo Chiquito in the Darien Gap.

"To tell you the truth, 80% die and 20% live. I'm not going to say that it's easy and that everyone should do it, but if I could do it, then so could they. It is really dangerous though. I swear, it's the worst thing I've been through in my life – something I'll never forget. It's awful. I almost drowned and so did my daughter. If somebody hadn't helped me, I would have drowned. In the jungle, my friend had his bag stolen, which had his money and his phones inside.

There is nothing here, absolutely nothing. There's nothing until you get here [Bajo Chiquito]. The rest is just water and rainforest".

Jennifer, a Venezuelan migrant. Village of Canaan Membrillo in the Darien Gap.

"I am a single mother to two children. My eldest is 16 years old and my youngest is 14. I'm a manager in HR administration. I've faced many challenges since the beginning. The first was having to leave my children [...] to be able to migrate and embark on this journey that is completely unknown. Nobody knows what to expect. Neither my boys nor me and the people I was with knew what was in store for us. It's even worse than people make out.

I think it's the worst thing anyone can experience in their life. I can't even find the words to describe it. I think if you spoke to everyone who has been through it, you'd see that people have had very different experiences; some people have had it worse. We may complain but we made it out safely. There are some who had it worse. There are people who died, mothers who came with their children, who took risks and lost their children or their husbands along the way. There was a woman whose husband died in a swamp, and she was left alone. We don't know if she made it out because she stayed with her husband.

I decided to migrate because I want a better life. God willing, I want to raise my children in the United States and give them a better quality of life – that's the goal".

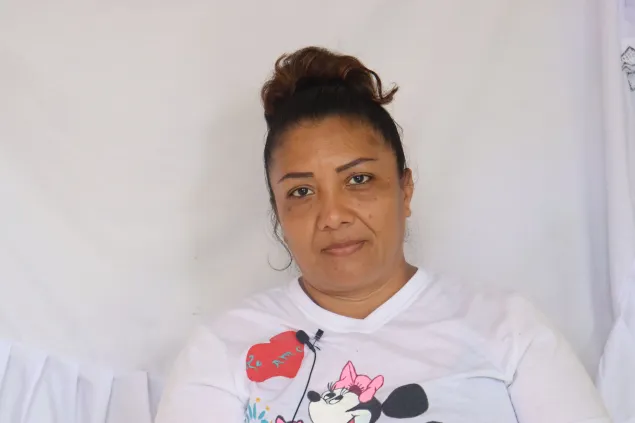

Yesenia, person deprived of their liberty.

"I'm Yesenia. I'd say that I'm a strong, determined, humble and modest woman. I'm a mother to four children, but only three of them are still with us. Three months ago, my only daughter passed away, and I hadn't been able to see her since I came here. I have three boys on the outside, one is still a minor and he's having a hard time because, with me being here, he doesn't want to continue studying, but I can't help him because I'm here.

My plan is to get out of here and to keep fighting for my children. I want to give them my best. I want them to see that, despite my mistake, I can keep going and I can provide for them in a different way, a better way".

Yeni, from a host community in the Emberá-Wounaan Comarca. Village of Canaan Membrillo in

"I am a single mother to four children. I am a strong Wounaan woman. I was born here and this is my home. I cook here, so I leave my children at home. I cook and I start to welcome migrants. I also serve in the shop. Sometimes migrants come but they haven't got any food, so I give them some. They tell us that they haven't got any money to buy a drink, and I give those that have nothing some items from the shop. Sometimes mothers come with their babies, but they haven't got any money to eat, so I give them some food from the kitchen".

Gabriel, a Venezuelan migrant.

"My journey started in 2016 in Venezuela. I left for Peru, then went down to Chile and then on to Argentina. I then went back up to Bolivia, and from there I made my way up through Peru, Ecuador and Colombia, and now I'm here in Central America. It's crazy. I've walked a lot and my life has changed a lot. I've gone from having a home to living on the streets. A lot of the time, I've had to live in difficult but not impossible conditions. My main goal is to settle down and live in peace and for everyone to be united".

Mexico and Central America: "The urgent need for a coordinated response to silent violence"

Olivier Dubois

Head of the ICRC's regional delegation for Mexico and Central America

It is this silent violence that worries us the most, because whole families and communities are no longer able to live in peace and follow their dreams, but this violence may go unnoticed. Only those who sit at a comfortable distance can act like nothing is happening and convince themselves that this silence is peaceful rather than fearful.