COVID-19: Lessons from Philippines jails show how to fight infectious coronavirus disease

As COVID-19 focuses the world’s attention on infectious diseases, we have our eyes on one of the most dangerous places for the spread of such outbreaks: prisons, where densely packed people and (often) limited access to health care make for a risky situation.

Overcrowding, poor ventilation and infrastructures, deficient health, hygiene and sanitation conditions favours the spread of infectious diseases – whether the novel coronavirus COVID-19 or tuberculosis (TB) which can rapidly affect a large number of people inside detention facilities. While COVID-19 is caused by a virus and TB by bacteria, both may have devastating effects on vulnerable groups such as the elderly and those with chronic diseases.

TB, for example, is known to be 100 times more prevalent in detention facilities than in the community. And based on the World Prison Brief database, the Philippines was ranked highest in the world in jail occupancy rate in their latest report. As of 19 March 2020, according to the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP), the congestion rate in their 467 jails is at 534 per cent.

Lessons learned from fighting TB in Philippines' jails could help inform the fight against the novel coronavirus COVID-19 inside prisons. They include infection control protocols (proper entry screening and mass screenings inside detention facilities); and creating isolation units for infected patients to halt the disease's further spread. An infirmary dedicated for the isolation and treatment of detainees with TB in the Calabarzon region – where some of the Philippines' most congested jails are located – is the first of its kind in the overstretched prison system in the country.

These factors pose an extra challenge when it comes to preventing, treating and containing infectious diseases. Furthermore, a significant proportion of the detainee population present vulnerabilities such as pre-existing medical conditions (high blood pressure, heart diseases, respiratory tract diseases, cancer or diabetes) and older age, which according to the World Health Organization (WHO) can lead to increased severity of the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic, if infected.

Support for this initiative is crucial to addressing the scattered demographic distribution of 44 jails all over this region which continue to impose logistical and public health challenges in the delivery of health services amidst TB endemic and the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic.

The ICRC, whose work includes visiting places of detention to ensure humane treatment, has been supporting Philippines authorities to address the causes and consequences of extreme jail congestion, among them, advocating for detainees' access to quality health care. We believe that further investment in the tuberculosis prevention programmes in Philippines strengthens the capacity of one of the most vulnerable prison systems in the world to fight other communicable diseases as well.

The ICRC has been visiting the regional TB Infirmary in Calamba, Laguna province, since 2014. We have provided material (lab supplies, personal protective equipment, TB mass screening supplies/equipment, etc.) and TB technical support (quarterly monitoring from the ICRC TB team and annual programme reviews from external consultants, building of linkages with DOH, provincial/city health offices and partners such as PBSP-Global Fund and USAID, and inputs for policy changes on infirmary operations). In 2019, ICRC also provided support to expand cells, renovate the kitchen facilities and TB laboratory.

The ICRC is continuously working to strengthen the overall prison health system in the Philippines through activities such as improving access to health care for inmates and enhancing the detection and control of TB. These include defining and implementing "inmate health records" and entry screening procedures; conducting and training jail health staff on TB mass screenings as part of early case detection efforts; improving facilities through infrastructure and material support for the detection, isolation and treatment of detainees with TB; and enhancing the referral system to public health facilities.

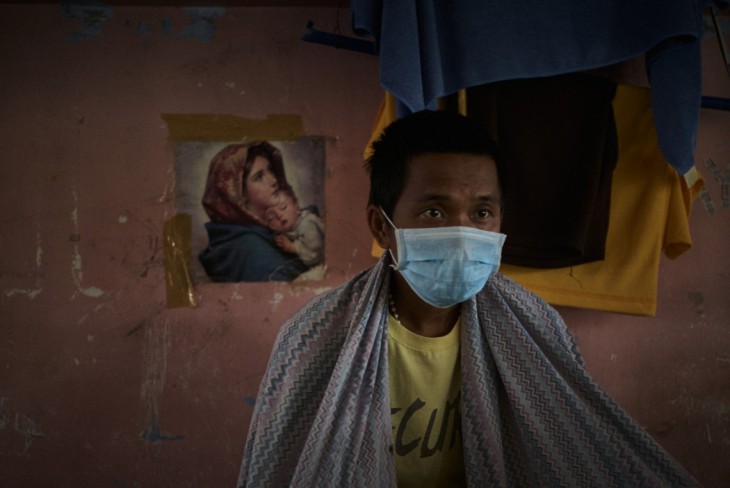

Overcrowding has been a challenge for many years inside Philippines jails. This photo was taken inside the Manila City Jail in early March. Preparedness is very important against infectious diseases as these can potentially spread fast inside the jails and infect not only inmates but jail staff and visiting family members. Jes AZNAR/ICRC

The regional tuberculosis infirmary in Calamba, Laguna province, is in a four-story building with consideration for adequate natural ventilation in grilled-type cells and a courtyard with basketball playground for sunning purposes. Tuberculosis patients are isolated according to their bacteriological status to prevent cross-contamination. Masks are a must for inmates, visitors and jail staff inside the facility. As of 16 March 2020, the infirmary had 300 inmate patients – 272 are males, 28 are females. Nine of them have multidrug-resistant TB. Photo: ICRC

An inmate, who is on the fifth month of his TB treatment, provides a sample of his sputum to the jail health staff. His sputum will be examined in the laboratory to determine if he has been cleared of TB infection or otherwise. Photo: ICRC

The elderly and those who have pre-existing medical conditions (high blood pressure, heart diseases, respiratory tract diseases, cancer or diabetes) are more vulnerable to TB as well as the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic. Jes AZNAR/ICRC

"Many years ago, when I applied for work, my X-ray findings suggested I had TB. I was treated for six months but I did not finish the course. I have been jailed for seven years in a congested facility. A mass screening was conducted there as well as sputum screening. There it was traced that I now had MDR TB, because I did not complete my treatment when I first had TB. I have been undergoing treatment for six months. In the first four months, it was tough because we had daily injections and a lot of medicines. I just hold on so I can get well. Now my treatment is ongoing so I can be cured." - "Rudy," inmate with MDR TB. Jes AZNAR/ICRC

"I first had TB in 2003. I took my medicines for only three months. I did not finish the treatment because I already felt better. I found out I had TB again when I was detained in 2015. They gave me injections for two months then tablets in the next seven months. At first, it was okay but later on I could barely walk. I forced myself to survive the treatment. The BJMP staff really helped. They pursued immediate treatment for me and other detainees who showed symptoms of TB. I have a child and I want to be with him again. He keeps me motivated. I've been praying to God to heal me. I tell myself to hang on a little more and I will be free soon. I really hope I can overcome this." - "Joey," 44-year-old inmate who was cured of TB at the Calamba infirmary. Jes AZNAR/ICRC

Good nutrition is especially important in preventing TB, but also during the treatment course. Early detection is also key in successfully treating an inmate with TB and lowering the risk of the disease's spread. "The infirmary supplied us with all the needed medicines in the six months of treatment. But I still ask my mother to bring me fruits and vitamins so I will not get TB again. Now inside our dorm, whenever I notice someone with TB symptoms – loss of appetite, non-stop coughing – I ask them, can you still endure it? I accompany them. I tell them, eat as much as you can. Drink a lot of water, if possible, more than seven glasses a day." - " Mike", an inmate who was treated for TB at the Calamba infirmary in 2014, and has been cured since. Jes AZNAR/ICRC

TB is curable – although the treatment duration is from six months for regular TB, and from nine months to two years for drug-resistant forms. Here, a jail health nurse goes through the records of each TB patient to prepare their medicines every morning. Every patient takes anywhere from two to 24 tablets daily, and in some cases, an additional two to four months of antibiotic injections. Photo: ICRC

"The side effects can be very challenging, and sometimes cause patients to discontinue treatment. These include nausea, headache, skin itching, body pains, stiffness, and at times, hearing loss. I lost my hearing in my right ear. Even if you fire a gun, I won't hear it. I also experience a lot of itching from drinking rifampicin. I don't regret undergoing treatment. Had I not taken my medicines, you won't be able to interview me anymore. I'd probably be dead already. My body felt like a lit candle that was slowly dying out." -"Carlo," inmate who was cured of TB. Jes AZNAR/ICRC

"What's good about the infirmary is that the TB cases in our jails are isolated and treated here. We remove them from a congested jail where there are surely a number of TB cases. It's like we are cleansing that jail by treating them here. That's what's good about this infirmary. There's one facility that caters to detainees with TB. They get cured from their illness. They are given health education and health service." - Daisy Ann Ancheta, National Tuberculosis Programme nurse who has been working since the start of the Calamba regional TB infirmary in 2012. Jes AZNAR/ICRC

A GeneXpert testing unit allows TB bacteria to be detected in the sputum of patients after only two hours. It also tests for rifampicin-resistant strains. The regional TB infirmary has two GeneXpert units – one of which was donated by the ICRC. With these, the infirmary can properly segregate and treat detainees with primary TB and those with rifampicin-resistant TB. Rifampicin-resistant cases will undergo further laboratory confirmation to identify the range of drug-resistance in Batangas Medical Center and the National TB Reference Laboratory. Photo: ICRC

"When I first learned that my husband had TB, my only desire was for him to get treated. It doesn't matter if he's far so long as he receives proper treatment. I visit him twice a week. It takes me an hour to visit him. We talk about the naughty things our grandchildren do. I also bring him food. At first, I was afraid to visit him but I thought he would feel sad if I didn't. And that instead of getting well here, he might turn for the worse. My being his wife overcame my fear of getting TB." – A woman visiting her husband who has just finished his TB treatment. Her husband was moved to the infirmary from a jail in Batangas in October 2019 upon TB diagnosis through one of the TB mass screenings. Jes AZNAR/ICRC

"Our leadership saw that inmates in our congested jails are more vulnerable to TB. As such, they set up this facility to better treat inmates with TB and to stop the further spread of TB in jails. Here, they will be attended by jail health staff and receive medicines. Their chances of recovering are much higher. Just because they are in jail, it does not mean that they should not receive the same standard of health care as are those in the community. They must be treated equally when it comes to standard quality health care. There should be no difference." – Jail superintendent Elizabeth Garceron, warden of Calamba regional TB infirmary. Jes AZNAR/ICRC

Aside from family, faith is what keeps many inmates with TB going. An inmate, who suspects he may have drug-resistant TB again, said: "I've been praying to God to heal me. I tell myself to hang on a little more and I will be free soon. I am always praying to him. I hope I can overcome this." Jes AZNAR/ICRC

"We prioritized support to the infirmary because we acknowledged BJMP's attempt to provide optimum TB care to inmates with TB. Being behind bars is already a huge suffering. As such, being ill inside the jail is an added burden. Some if not most of the detainees will eventually be set free. If they're sick upon release, they can infect their family members and co-workers. The ICRC shares the BJMP view that detainees deserve the same standard of health care as are in the community. Detention authorities face a lot of limitations. The ICRC calls on all partners in health to help the detention authorities so they can provide better health care to inmates." – Ramon Paulo Eustaquio, ICRC health field officer in charge of supporting the TB program in jails. Photo: ICRC