Somalia food crisis – drought, conflict and the fight for survival

Sat on the edge of her bed, Wiilo Maalim Nuuro cradles her daughter, Nafiso. The two-year-old is severely malnourished and is undergoing life-saving treatment.

She is far from alone. The intensive care unit (ICU) at the main hospital in Baidoa, in southern Somalia, is bustling with medics and patients.

Shrill cries punctuate the hot, humid air. This is no place any parent wants to be, yet it is also their last hope in what is Somalia's latest food crisis.

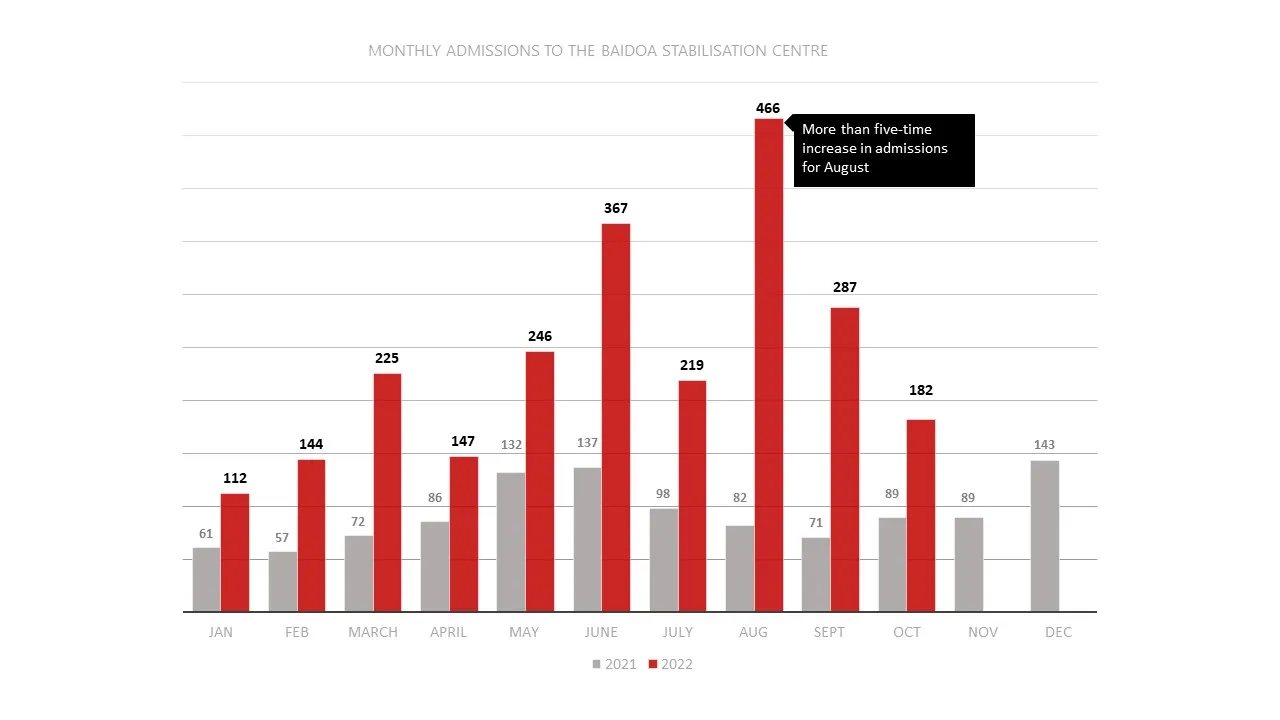

The ICU only admits children aged under five and only the most critical cases. Admissions are far in excess of last year.

"We hear stories of children arriving at the hospital in the last minutes of their life, when there is simply nothing that can be done," said Ali Abshir Mursal, an ICRC nutritionist working at the hospital.

"It's awful. Sometimes we get reports of mothers coming to the hospital, but the child dies on the way."

Two-year-old Nafiso and her mother

Severely malnourished children are at increased risk of additional medical complications such as pneumonia, acute diarrhoea, respiratory tract infections, anaemia, skin infections and measles.

Nafiso has kwashiorkor, a form of severe protein malnutrition. She is receiving nutritious milk supplements as medics try to stabilize her condition.

All her mother can do is pray that her only child pulls through.

At one end of the ward a large whiteboard lists the names of the children and their mothers, along with scheduled feeding times. The infants are weighed every morning at 6am and their vital signs are meticulously monitored.

Oxygen machines drone quietly in the background, providing support to children who need help breathing.

Some children are too weak to feed so have to be fed nutritional milk via a nasal tube.

Aamino Mohamud’s eight-month-old daughter was admitted with severe malnutrition and oedema

The ward is uncomfortably hot. Brief rains have given rise to swarms of mosquitoes. The windows are kept closed in a vain attempt to keep them out and to keep the children warm.

The ICU is part of what's known as a stabilization centre. The centre has seen a drastic increase in cases of severe malnutrition this year.

Between January-October, 2,395 children were admitted to the centre – nearly three times the number for the same period in 2021. A total of 63 children have died.

The ICRC supports a second stabilization centre in the port city of Kismayo, which has also seen a spike in cases this year.

The ICRC provides medical supplies and nutritional products to both stabilisation centres. It also offers financial support for the staff.

When conflict and climate collide

The journey to Baidoa from rural areas is dangerous and takes time due to the volatile security situation. There are many checkpoints along the way. Recent showers have also made the terrain more difficult.

"People come from a long way out of town, it might take them 24 hours to get to the hospital," said Mursal.

"Baidoa is a big town, but the drought and conflict have seen an influx of people coming in search of food and health care. It places a strain on everything."

Somalia is no stranger to food shortages, but a combination of factors have conspired to create a dire crisis this year.

The conflict, which has raged for around three decades, has forced countless people from their homes and restricted access to farmland, pasture for animals and health-care services.

Conflict, climate shocks and global inflation have resulted in critical food shortages

Repeated failed rains have led to a severe drought – the worst in years – that has ravaged crops and livestock.

Global inflation and a shortage of grain due to the conflict in Ukraine have also played their part. The upshot is that more than seven million people are in urgent need of food and water.

Hostilities in the east-African nation are getting worse. Between January to October, the ICRC recorded 57 mass casualty incidents, related to conflict, across four ICRC-supported hospitals.

That figure is up by nearly 30 per cent on the same period last year.

The hospitals treated more than 2,100 patients with conflict-related injuries in that same period, up by nearly 200 on last year's figure.

"It is very difficult to know how bad the situation is in areas we can't access due to insecurity," said Mursal.

"We can't estimate, there is no data."

Breaking point

Giving cash to families is one way the ICRC tries to help people to overcome lost livelihoods or food shortages. At the end of August, more than 150,000 households received enough money to buy food for a month.

To help build resilience in the face of worsening climate shocks, the ICRC also supports agricultural cooperatives with training, drought-resistant seeds and farming tools.

Mohamed Abdille Abdi, an ICRC economic security expert, is part of the team that carries out assessments ahead of aid operations.

While out on an assessment, Abdi recalled meeting one household that comprised only children, the eldest being just 15 years old.

Both parents had died and the children had to rely on support from the community around them to survive.

"Somalis have that social network where people support each other during these times," said Abdi.

"That social network is dwindling because everyone now is really at breaking point."

Back at the stabilization centre, little Nafiso's condition has improved after more than two weeks of treatment.

Mother and daughter will soon make their way back to an informal camp on the edge of town, where they will join the masses of people displaced by conflict and drought.

Hope now lies in the current rainy season, which will cultivate a new optimism for the future.

If the rains materialise.

This piece was published by the ICRC team in the UK and Ireland. Find out more about our work and follow us on Twitter.