War in Cities: Tripoli, Libya

When wars are fought in cities, it is civilians who bear the brunt. In this new series we explore the devastating impact on people who have seen their streets become the frontline.

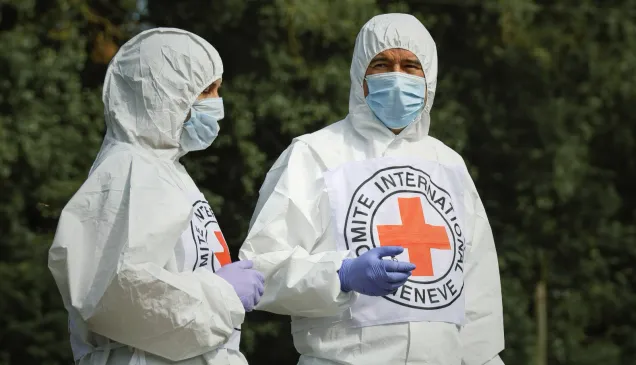

We spoke with Youser Benali, who works as a programme officer responsible for relief and livelihoods activities for the ICRC in Tripoli, Libya.

What's life like in Tripoli at the moment?

At the moment the situation in Tripoli is relatively calm. We are in a post-conflict phase. But now of course we are also dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic.

We have many ongoing issues such as fuel shortages, which make it difficult for people to get to work or come together with their family. We also have ongoing electricity blackouts. These often happen around midday, when women are cooking and preparing food for their families.

The last round of conflict lasted for around a year and a half, from April 2019 to August 2020.

The damage that was done during that time was very intense. There was extensive damage to people's homes, infrastructure and municipal buildings.

It was a very difficult time and it felt as though it went on for a longer than it did.

What was Tripoli like during the conflict?

It was a strange situation to live in because the fighting was in the south, just on the outskirts of the capital. But the eastern part of the city was functioning semi-normally.

You would see armed groups going back and forth, either coming from, or going to the frontline. There was a strange mixture of civilians and armed groups. The sound of shelling at night was quitescary, and the travelling outside the city was difficult with the airport being occasionally hit. Health and medical services were also affected by the war as they had to take care of a large number of injured.

This is what 10 years of war has done to Libya. pic.twitter.com/X3v6a2uYBF

— ICRC (@ICRC) February 18, 2021

I suppose you get used to it, in a way. It wasn't that everybody thought that was normal. But because it went on for so long...it became the norm.

That was a very tough time. In the past, we've had conflicts but they've never lasted as long as this one.

Because people had been forced to leave their homes due to the conflict, many were living in collective centres. These are places like schools, old government buildings, and buildings near to a mosque, where people could shelter together.

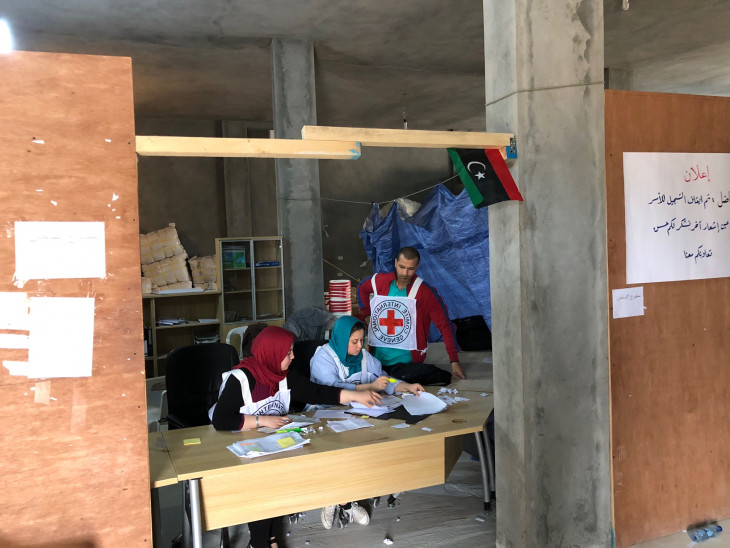

A big part of what we were doing was working to make these centres safe places to live, wherever possible. We would go to one of these collective centres, and think, OK, what do they need?

We were distributing essential items such as food, soap and water. People had nothing. We also restored the water infrastructure in some of these shelters, which was especially important after Covid arrived.

What are the main issues affecting the people you are supporting? What do they tell you?

In 2019, after the fighting resulted in many people fleeing their homes, we did a very large household survey to understand people's needs and situation. We would go around visiting people's houses, or at least where they were living.

One story stays in my mind to this day.

We went into someone's household and we sat down to ask this man how he was and what had happened to him – questions like 'When did you leave? Where did you go, and so on.'

And at some point, they don't treat you as a person that is there to 'assess their needs'. It's just a shoulder to shoulder conversation.

This man had fled the fighting and had been stopped at a checkpoint.

He was in his car with his two daughters, his son and his wife, and they checked his trunk. In it they found his old military uniform.

Here in Libya military service used to be mandatory and so lots of people have old uniforms they use for things like cleaning the car or jobs around the house.

This man was just crossing a checkpoint, leaving his house because of conflict. And then they said no, they didn't believe him. They accused him of him being a military person and said he was probably involved with one of the armed groups.

He said they assaulted him in front of his daughters, his wife.

And they took his son, who was only a young man.

And that is everything I know about their story. I think of him still, very often. Has this family found their son alive? Or have they learned that he has died? Or are they still waiting, not knowing.

The story really gets me thinking. I can imagine what happened to just that one family, and also to so many others.

How did the ICRC respond?

Overall, nearly a million people in Libya benefited last year from one or more ICRC services whether directly through provision of food, essential household items and cash, or through ICRC's support to water and healthcare services.

How are the needs changing over time?

We initially provided the items people needed, as part of the first emergency response. But then over the longer period we developed a large cash assistance programme to allow people to buy food and items that they and their family need most.

Some of our cash assistance programmes lasted for months because the people in the collective shelters are the most vulnerable. They don't have the means to rent and they don't have the relatives to stay with. We provided cash assistance as well as furniture, shelter - whatever was needed.

Even today there are still some people that are living in collective shelters, because there is too much damage to their homes, they cannot go back.

And it's because a lot of the damage was to infrastructure, and that's very expensive to repair, especially with a bad economy.

Buying material for buildings costs a lot and they don't have a lot of funds, because... you wouldn't if you drained all your funds trying to survive being displaced for a year and a half.

What is cash assistance?

While emergency aid saves lives and mitigates the most immediate effects of conflict, we always try to keep sight of our ultimate aim: restoring people's ability to provide for themselves. In some cases, aid takes the form of small cash grants so that the families themselves can choose how to meet their needs; local markets and producers also benefit indirectly from this aid. In other cases, we help people start a small business or produce their own food. Read more about our cash assistance work.

What is the culture like in Tripoli, what stands out?

I honestly think this city has a lot to give in that it has a very rich history that people might not be aware of.

There's a unique culture here, because it's the capital and it hosts people from other cities.

You've got a lot of different backgrounds living together, it is very multicultural.

The other thing is we love our food. Honestly, food is the only entertainment here. Also, we like our coffee - we are religious when it comes to our coffee.

What's your favourite thing about Tripoli?

For me the shoreline is the best part because here we're on the Mediterranean. It's a very nice view especially during the summer when it's cool and calm.

That's my favourite part of the city. Whenever I go somewhere else where there isn't a sea, I feel very grateful when I get home. My house is almost on the same street as the coast, so I'm very lucky.

Why is fighting in cities so harmful?

We have been experiencing conflict, off and on, for over a decade now, but even when the fighting stops, people cannot just return to normality.

Their houses have been destroyed, their neighbourhoods littered with unexploded devices, their livelihoods gone. When wars are fought in cities like this, it is so much harder for people to rebuild their lives.

Join our community to reduce the human cost

of urban warfare