Philippines: Understanding challenges in detention through Health Information System

While congestion in Philippine jails has been decreasing in the last eight years, it remains a systemic problem resulting to numerous humanitarian consequences. In the 426 jails managed by the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP), the average congestion rate as of May 2025 is 296% — a decrease of 26% from the average recorded in May 2024. Despite the improvement, jails are still overpopulated.

Overcrowding means detainees have limited movement, sleeping spaces and ventilation; and compete with access to water, sanitary facilities and healthcare. Overcrowding also means disease-causing bacteria and viruses spread faster among detainees, their visitors, and jail staff.

However, addressing these health issues in detention is another problem. Prior to 2024, there was no standard medical recording in place in BJMP jails. Detainees’ health records were disorganized. Information from consultations were written in loose sheets of papers; these were stored in places where they could easily be accessed, destroyed or lost. The lack of a standard recording system also meant that reliable health data was unavailable, making it hard for the authorities to make decisions in connection to the delivery of basic healthcare to detainees.

The situation led the BJMP to work with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), an international humanitarian organization with long experience in working in detention facilities around the world, to come up with the Health Information System (HIS), where standardized patient forms, similar to those available in hospitals, are used in jails. The HIS is now being implemented in all BJMP jails nationwide where around 116,000 people are detained.

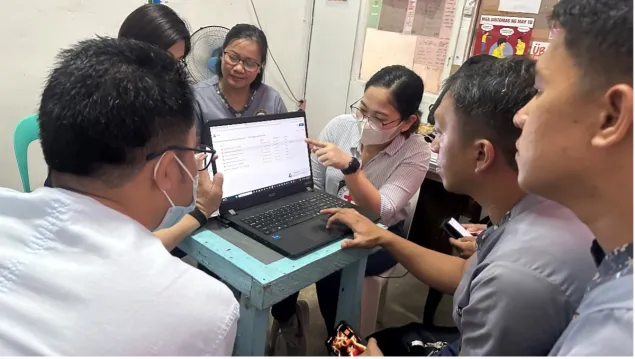

The ICRC provided financial and technical support to make HIS a reality, said Harry Tubangi, the organization’s health field officer. The BJMP and the ICRC organized a series of capacity-building sessions where the staff learned how to fill up and use the patient forms, the process of incorporating them in their work in the jail clinic, and the ways to analyze the data. The staff were also taught to keep the patient forms in safe places inside the jails, as these were confidential.

“Filling up the forms and keeping them in secure areas are just the initial steps,” Tubangi said. “The information collected from the forms are fed into an electronic database and submitted regularly to the BJMP’s headquarters in Metro Manila. The data can be submitted even by jails located in remote areas. We worked with BJMP officials so they know how to monitor or conduct checks on data quality to ensure the accuracy of the information. Mechanisms were also put in place to ensure that the data is protected to prevent tampering.”

Marianne Legaspi (center), a health field officer for the International Committee of the Red Cross, during the capacity building sessions with the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology.

Through the use of the data from the patient forms, the BJMP is informed of the common diseases present in certain jails and communities. This data can be shared with the Department of Health or the local government unit, both of which can look into trends to better manage or prevent potential outbreaks of the diseases that have been identified.

Tubangi added: “With the system in place, we expect that it will be easier for nurses or doctors to endorse a detainee to their colleagues. Now that the forms are standardized, healthcare workers will have a better understanding of a patient’s health history when that person is endorsed to them.”

“In the past, health workers were encumbered with responding to emergencies or symptomatic care. With HIS, we expect that nurses and doctors can focus more on improving a detainee’s health condition.”

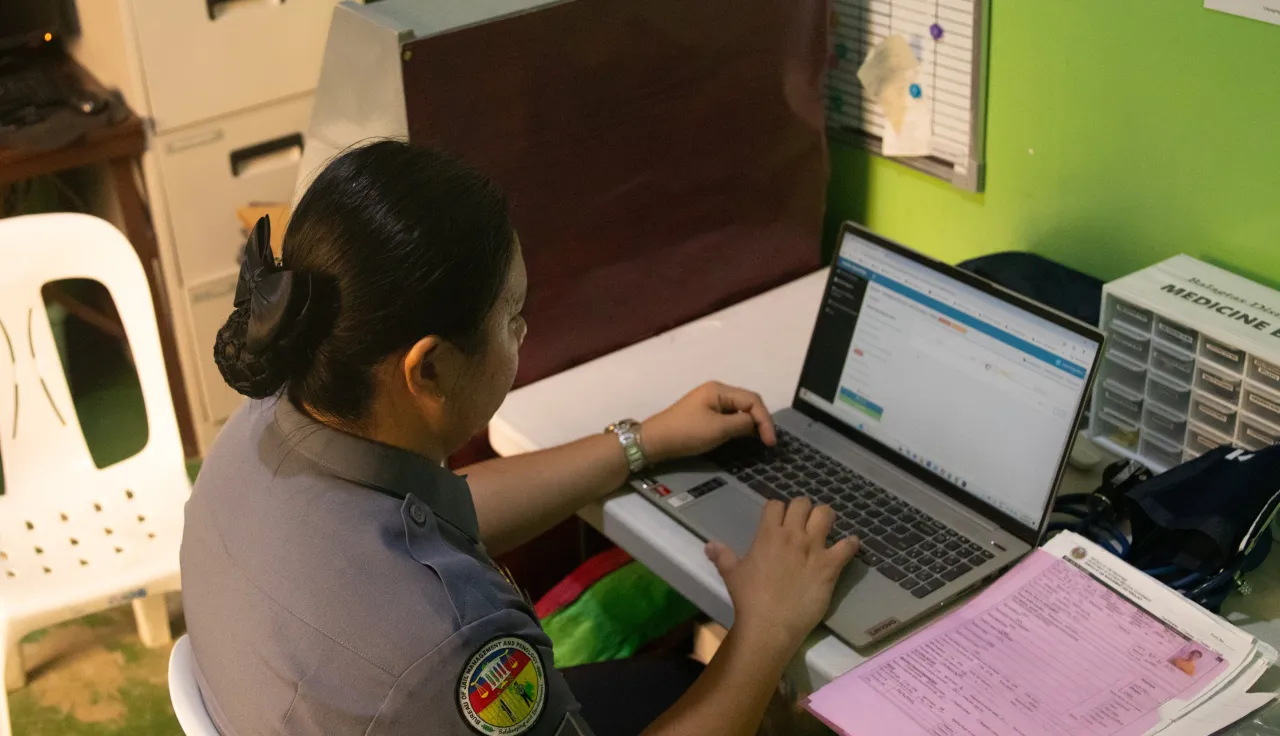

Jail Officer Anna Lalaine Casaje is one of the BJMP officers who has been trained in using the HIS. She said the system protects nurses like her in case something goes wrong during patient care.

“In nursing school, we were taught that if we didn’t write any information in the patients’ records, such as checkups or medicines given, that means they were never done. Now that we have proper documentation, we are better protected from complaints. The documents could serve as proof that the nurses have done their jobs properly especially during consultations,” she said.

Jail Officer 2 Anna Lalaine Casaje is one of the detention nurses who has been trained in using the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology’s Health Information System.

Jail Officer 2 Casaje during the check-up of a long-term detainee in Balagtas District Jail, where she currently works.

While the HIS is envisioned to make the work of nurses and doctors more efficient, the system requires them to be more diligent during consultations with detainees. They need to spend more time understanding patients’ needs to ensure that all information written in the forms are complete and accurate. They also need to learn clinical practice guidelines and expand their knowledge to make the most out of HIS. Doctors and nurses should be capable of analyzing and evaluating the information gathered through the system.

The BJMP and ICRC are currently monitoring the use of the HIS to understand if detainees have benefitted from the system and if the health issues in jails are being addressed. Detention officials and the ICRC are also looking at other ways in which they could improve the delivery of basic healthcare.

“As a neutral and impartial humanitarian organization, the ICRC works to ensure humane treatment and access to health care for detainees, regardless of the reasons behind their arrest. The ICRC remains committed to working with government institutions and partners to improve detention conditions and protect the health of detainees,” Tubangi said.