Heirs of War: Isolation or Reintegration?

By Ariane Tombet, Head of Mission ICRC Nicaragua; Kian Abbassian, Head of Mission ICRC Guatemala; Olivier Martin, Head of Mission ICRC El Salvador; Alexandre Formisano, Head of Mission, ICRC Honduras

Although Central America ceased to be the scene of wars between armed forces and guerrilla groups several decades ago, social tensions and armed violence remain worryingly rampant and widespread. The inhabitants of some of the countries in the region, trapped in a seemingly endless spiral of violence, continue to face the terrible consequences of such situations, including killings, armed attacks, kidnappings and extortion.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is all too familiar with the realities of the situation; for years now, it has been going into these communities and listening to people who have had to arm themselves with patience as they wait for some kind of response from the government, which has so far failed to materialize or proved insufficient.

In El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and other countries in the region, we encounter many women and men who have lived through the conflicts of the past and tell us of their suffering in the present. People feel that they are hostage to a recycled violence with manifold manifestations that has its roots in the deterioration of the social fabric and widening inequalities. They have to put up with people reminding them on a daily basis who rules their street, an enemy in the shadows who forces them to pay a toll and holds their hopes and their future to ransom.

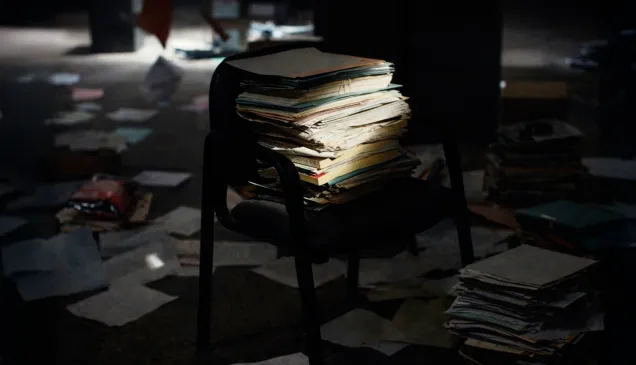

The other side of the coin is also very familiar to our specialists: the thousands of people deprived of their liberty who we visit in prisons in Central America. Many of them are from the same communities where we carry out projects to mitigate the humanitarian consequences of urban violence. Those who belonged to a gang tell us how the maras gave them opportunities that their neighbourhood could not offer them.

People deprived of their liberty cannot just be ignored by the rest of us. Maybe we should see them not as society’s rejects but as a reflection of the flaws in our communities, a symbol of our failure? Each of their faces reflects an unfinished or incomplete society, injustices that we have allowed to grow and that have been met with a violence reminiscent of the conflicts we thought we had left behind.However they ended up in prison, people deprived of their liberty are entitled to basic legal guarantees. Their life, dignity and rights must be respected, and they must not be subjected to physical or mental torture or treated in a cruel or degrading manner.

The way to do this is to adopt a people-centred prison management approach, ensure that inmates have access to essential health services and can be visited by their families, prevent the abusive use of detention and palliate the lack of prison privileges.The work of the ICRC in this area is based on the Nelson Mandela Rules, the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners adopted in 1955 and revised in 2015 by the United Nations. They contain basic recommendations that should guide the implementation of prison policies in any State.

The women and men of Central America believe in peaceful coexistence, solidarity, education and progress. Although we may find it hard to accept, people deprived of their liberty continue to form part of society and play a role in it. The State and the society it represents cannot give up on or disregard the citizens that one day failed them; they must move away from a purely punitive approach which obstructs reintegration, reform the system to humanize prisons and advocate for an efficient criminal justice system and rehabilitation for offenders to reduce the risk of social exclusion upon release and permit their reintegration into the community to lead a productive life.