The missing in Latin America: Families will not stop searching, nor will we stop helping

The impact of the disappearance of a loved one is one of the most damaging and lasting humanitarian consequences of armed conflicts, other situations of violence, migration and natural disasters. The suffering experienced by the families of the missing never ends, and neither does their search.

Not only are disappearances an immeasurable tragedy for the affected families and communities, they also pose a major obstacle to peace.

The problem of disappearances takes on a truly global dimension when people go missing during migration. Thousands of people disappear every year along perilous migration routes around the world, and the vast majority remain unaccounted for.

In Latin America, hundreds of thousands of people have been reported missing in connection with past and present armed conflicts, continued armed violence, the constant tide of migration and natural disasters. Tackling this problem is a daunting humanitarian challenge for the region.

There is a lack of reliable statistics on the number of people missing across the continent. Many countries have failed to develop effective centralized systems to address the problem, making it difficult to design and invest in public policies to prevent and help resolve cases of disappearances and to respond to the needs of relatives.

On the whole, the services that do exist are unconnected, and families have to go knocking on doors at multiple agencies where they receive piecemeal information.

It is estimated that at least 83,000 people have disappeared in Colombia, more than 20,000 in Peru, over 45,000 in Guatemala and more than 5,000 in El Salvador in connection with the armed conflicts that have taken place in the region over the last few decades.

Today, people continue to disappear in considerable numbers in Latin America as a result of different situations of violence. In Mexico, more than 40,000 people were reported missing between 2006 and 2019, and in Brazil, more than 80,000 cases were reported in 2017 (2018 figures not yet available).

For families in countries such as Guatemala and Colombia, the wait is endless. Some of these families have had no news of their missing loved ones for more than 20 years.

Far from being a problem of the past, disappearances are very much a current issue.

Many people from Latin America disappear every year along migration routes while others are abducted or killed in connection with armed violence or go missing as a result of natural disasters.

Although circumstances differ according to the context, the families have similar needs: they need to know what happened to their missing relative; they lack institutional support in their search; they feel discriminated against and forgotten by society; their mental health is affected by the years of waiting and searching; and they do not receive the support they need.

State authorities have the primary responsibility for preventing disappearances and responding to the needs of the families of the missing. However, the ICRC also has an important role to play. In order to help address these needs, the ICRC has multidisciplinary teams comprising legal, forensic, psychosocial and other professionals that provide support to family members and the authorities.

We engage in dialogue with the local authorities and offer them technical support to develop or improve legislation and to create or strengthen search and family assistance mechanisms.

For instance, in Peru we promoted the Law on the Search for Missing Persons, which was passed in June 2016. We also participated in a process that culminated in the enactment, two years later, of an executive order to create the Genetic Data Bank to assist in the search for people who went missing in the country during the period of violence (1980–2000).

In Mexico, at the beginning of 2018, a law on enforced disappearances came into force, providing for the creation of the National Search System. The law was designed in cooperation with the families of missing persons, and they were instrumental in getting it passed. We made recommendations throughout the drafting process and are providing support for its implementation both at the federal level and in the country's different states.

In El Salvador, we are working alongside families and the Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman (PDDH) on a legislative proposal concerning missing migrants and their families.

During 2018 in the region:

| 3,515 tracing requests remained open in 11 countries at the end of 2018 | |

| 1,165 new tracing requests were opened in 9 different contexts | |

| 287,310 telephone calls were provided for separated family members | |

| 1,137 families of missing persons received psychological and psychosocial support in 4 countries* | |

| In 9 countries forensic services were provided for humanitarian purposes* | |

| 6 countries received advice on the development of national legislation and measures pertaining to missing persons and their families* |

* Estimated figures

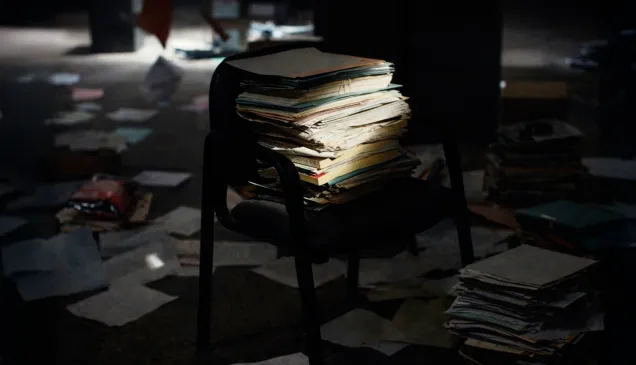

Eliana disappeared in 2007, two blocks from her house, in the north-east of Colombia. Her mother and grandmother keep her room just as it was in the hope that one day she will return.

Family members cannot rest until they at least have a place to lay flowers or light candles for their loved ones.

What encourages and comforts me is when someone says: “Do not give up, you will find your son; everything will be okay.” – Mirian dos Santos Almeida, the mother of Alison who disappeared on 24 August 2013. </h2>