Artificial Intelligence, Ethics and Armed Conflict

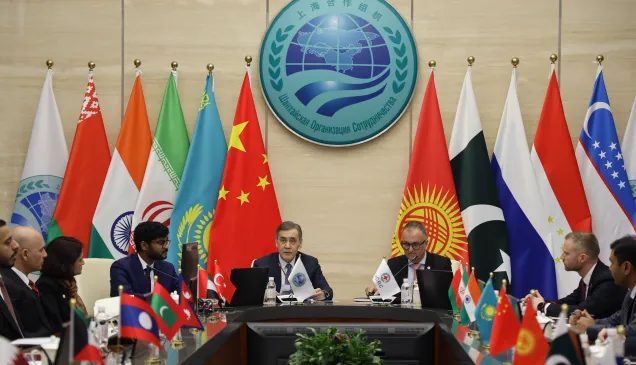

Keynote Address by Ms. Fiona Antonnette Barnaby, Head of the Humanitarian Affairs and Policy Unit, ICRC Regional Delegation for East Asia, delivered at the Fourth Soochow International Humanitarian Forum, Suzhou, China, September 5, 2025.

Mr He Wei, President of the Red Cross Society of China (RCSC) and Mr Zhang Xiaohong, Party Secretary of Suzhou University

Excellencies,

Ladies and gentlemen,

Allow me to begin by thanking the Red Cross Society of China, the Chinese Red Cross Foundation, the International Academy of Red Cross, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC), and the charity partners of the Red Cross Society of China, for organising the 4th Soochow International Humanitarian Forum, with the theme “Humanitarian Action in the AI Era: Connectivity and Resilience”.

Today, I want to talk about Artificial Intelligence, Ethics and armed conflict.

As the ICRC President, Mirjana Spoljaric recently said: The reality can’t be ignored any longer: we are living in a decade defined by war.

To her statement, related to the theme of this Forum, I would further add that we are living in a decade that will be defined by artificial intelligence.

An increasingly digitalised and connected world is an opportunity in the social, economic, development, humanitarian, information and communication spheres.

- It can help save and improve lives in situations of armed conflict.

- It can deliver goods and services such as medical services for affected populations; help communities access important lifesaving information and restore or maintain family links in an armed conflict.

This is no surprise as the advancements in technology in the digital domain continue to tout a variety of benefits and inspire a fear of missing out in humanitarians who do not want to miss the train. Nevertheless, these advancements, also present several risks to conflict affected populations and humanitarian organisations trying to help them. I share three trends:

- Artificial intelligence employed in cyber operations that target civilians or civilian infrastructure, disrupting essential services provided by such infrastructure.

- The spread of harmful information in conflict settings, for ex. by using “deepfake” technology to make realistic - yet fake – audio and video content, that can seriously impact conflict affected populations, trigger displacement, influence the intensity of the conflict, to name just a few consequences.

- AI being used to support military decision-making including managing war without human input.

According to a recent news report, AI software, developed by an armed force in an ongoing conflict, identified up to 37,000 potential targets in an area. That appears to be amazingly effective and seems to optimise military resources. The downside: The same programme factored in an error margin of 10%, i.e. 3,700 people who should not be targeted and secondly, the permission for the attack was granted or the attack was considered legal, because the programme identified a certain number of civilians as “acceptable” collateral damage, depending on their rank. Artificial intelligence accelerates the pace of war and appears to “enhance” or “improve” IHL complgiance in attacks. Welcome to war: digitalised, sped up and in self-driving mode.

Nothing is either good or bad except thinking makes it so.

AI is neither good nor bad, except thinking or rather, human thinking, makes it so.

In fact, the value of AI is not served by mere binary reflections. Humans develop AI and humans decide when and how to use this technology in armed conflict. Thus, the ICRC argues that any new technology, and for that matter, any new weapon, must comply with humanitarian rules or ethics. I will not go into this in greater detail as this afternoon, we will hear more on the Opportunities and Challenges of AI in Armed Conflict.

The rules that govern how parties fight in war do not specifically regulate AI or autonomous weapons or the digital space. For that matter, the rules of war crafted over time that are now known as international humanitarian law or (IHL), refer to three specific domains of battle – in the air, at sea and on land. Over time, with the onset of new domains where wars can be fought, such as outer space, the digital space and even the low altitude space, the ICRC’s mantra remains the same: the rules apply to the use of any weapon or manner of conducting warfare in any space – there is no gap in governance or regulation. There are no black holes, grey zones or ungoverned spaces. The rules and ethics that seek to ensure the preservation of a modicum of humanity in armed conflict, continue to apply irrespective of the domain in which an armed conflict is occurring and irrespective of the digital tool being used. Thus, the ethics or rules about how we fight a war are “tech neutral” even if tech itself is not neutral.

Thus, the ICRC engages tech stakeholders, be they developers, users, companies, practitioners, aficionados, advocates, and even opponents, on the potential impact of AI and tech in general, on people affected by conflict and on humanitarian action.

As we do, we notice a disturbing change in language in the humanitarian sector itself that reveals a “commodification”, “privatisation” or “marketisation” of the sector and shifts in how we describe how the humanitarian sector functions. Thus, we now talk about improving “productivity” instead of impact, we want innovation to ensure “scalability” instead of aiming at relevance; people affected by armed conflict have become “customers” and “clients” of humanitarian “services”; donors request “ROI” or returns on investment; and private sector partners offer expertise on how to leverage market opportunities for “social good”. Is this changing the humanitarian sector’s metric from quality to quantity? Can we accept the potential “returns” on our investment in tech solutions and on their utility while maintaining the compass of our professional ethics and values. Is AI a solution in search of a humanitarian problem?

As the digital domain evolves at lightning speed, the challenge for humanitarian organisations, is ensuring we are viewed as and engaged with, as neutral and independent humanitarian actors. If digital connectivity and resilience are part of the geopolitical contest, humanitarians must effectively manage their dependence on States, donors and affected populations for access, funds and acceptance to ensure we can keep working in a neutral and independent manner.

To do so, the ICRC has adopted and published its AI Policy in 2024 as an aspirational tool meant to support the ICRC’s continuous efforts to use digital technologies responsibly and in line with its humanitarian mandate. The Policy sets a value-based approach to AI, which is about humanitarian principles (Humanity, Impartiality, Neutrality and Independence) and about enabling and learning, meaning to foster ethical and impactful innovation as well as competence and capacity building. The Policy also introduces its guiding principles for AI, which include proportionality, precaution, and “do no harm” & safety and security & transparency and “explainability” & responsibility and accountability.

To summarise,

- The digital space is not a lawless space, including during armed conflict.

- States, tech companies and other actors are best placed to ensure the responsible and ethical use of AI. A good example is China’s Global AI Governance Initiative.

- They can and are encouraged to craft digital tools that comply with IHL and humanitarian principles and ethics particularly in armed conflict.

- Protecting civilians from digital threats requires investment in legislation, policies and practices. This is in line with the Resolution on ICT in armed conflicts adopted at last year’s 34th International Conference of the RCRC Movement.

- Digital technologies, like AI, have the potential for many applications in the humanitarian sector. ICRC and others in the sector should and can, responsibly and ethically explore AI within the guardrails of their humanitarian principles.

Digital technology is neither good nor bad. Rather it is us, its developers, its users, its consumers, that can make it either.

I conclude by wishing you fruitful, thought-provoking and intelligent discussions over the next two days.

Please do take a little time to experience our exhibition, installed just outside the conference room that touches on several of important questions.

In my humble view, the object of these two days, is to identify the right questions we need to consider as we continue to advance in our reflections and actions on AI in armed conflict.

Thank you.