A lost generation – drawings from the children of Al-Hol, Syria

Everyone has hopes and dreams. But for the thousands of children still trapped in Al-Hol, hope is in very short supply.

Around 55,000 people are currently stuck in the sprawling camp, in north-east Syria. An estimated two thirds of the camp's population are children, most are under the age of five.

"There's no future for the children here," said Nathalie Nyamukeba, a clinical psychologist with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

If you ask them what their dreams are, they say 'I don't know.'

They're living in a camp where there is no hope, no education, where they don't know what will happen tomorrow. They live amid fear and violence every day.

There are children who have spent their whole life in the camp, without ever setting foot outside its perimeter.

Some were born and have died in the camp – the entirety of their short lives spent in a place of utter misery.

Conditions are appalling. In winter, tents get flooded after heavy rainfall, while temperatures can drop to near freezing.

In summer, the parched earth gets whipped up by the wind to form dust storms. Temperatures reach more than 45 degrees Celsius.

Child's play

Together with the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, the ICRC runs a hospital in the camp. The hospital handled more than 11,000 medical cases in 2021 and more than 8,000 in 2022.

Last year, 925 people received mental health and psychosocial support at the hospital.

Patients often display psychosomatic symptoms, such as lack of sleep, heart palpitations, back pain, headaches, loss of appetite, skin problems and enuresis (bedwetting).

Other complaints include unexplained fear, aggressive behaviour, inability to concentrate, constant worrying, low self-esteem, social isolation and suicidal thoughts – even among children.

"I've met a couple of children, not older than 11, who have had suicidal thoughts," said Nyamukeba.

"They said they didn't want to live anymore. 'I hope God can take me and just leave this life.' These words are beyond anything that you would expect from a child."

The ICRC, with the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, offers mental health and psychosocial support to anyone needing help.

Most of the children who receive help are Syrian or Iraqi. Others are from the section of the camp where people of different nationalities are housed, in other words, children of foreign nationals who are stranded. There are more than 60 nationalities present in the camp.

Recreational activities such as playing or drawing can help children to express their feelings. Some drawings, understandably, have negative connotations.

"It's really difficult when you see those children without any future, who play with stones, who don't know how to hold a pencil, it's very painful," said Nyamukeba.

"They are a lost generation and it's not their fault. They are not responsible. As human beings, we need to find a humane way forward."

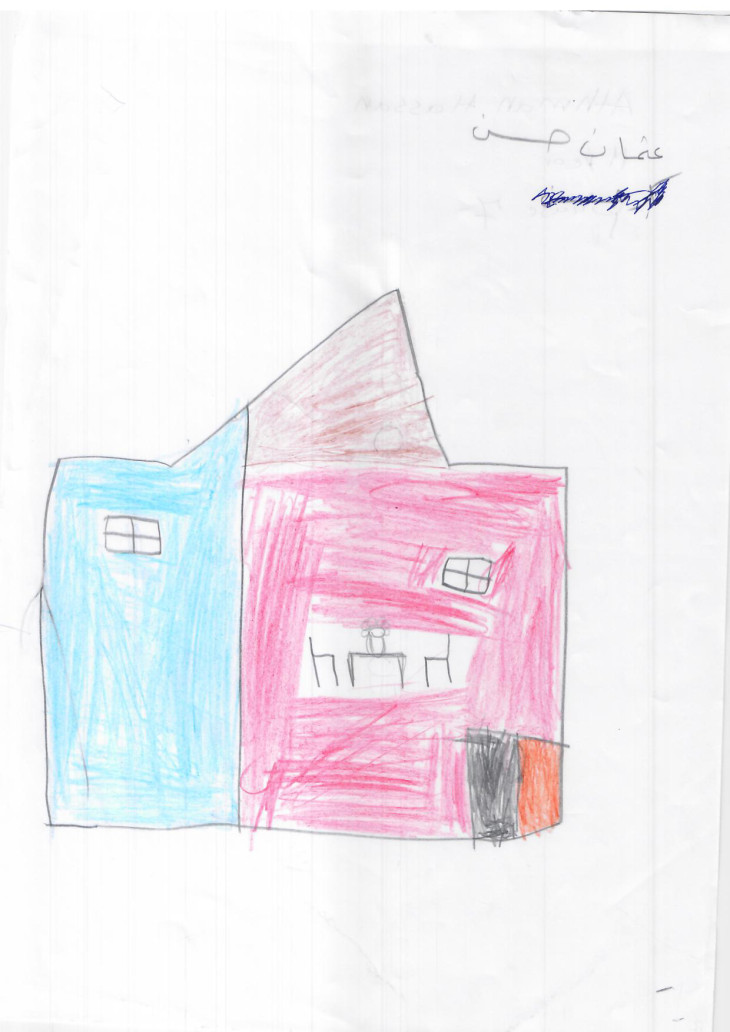

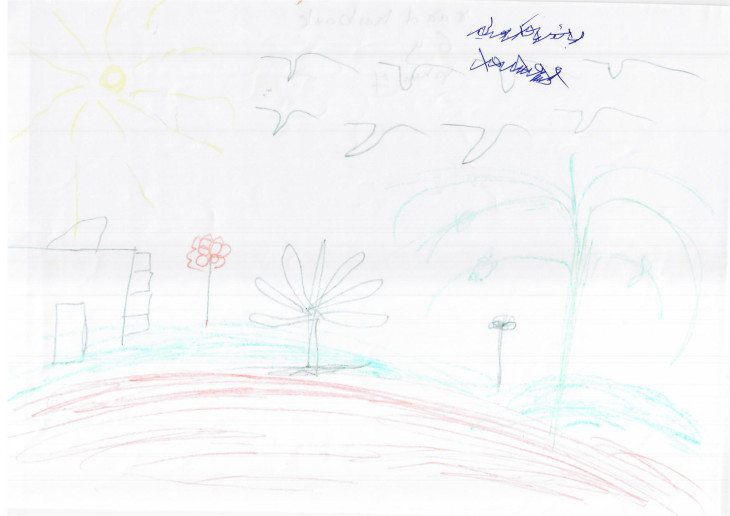

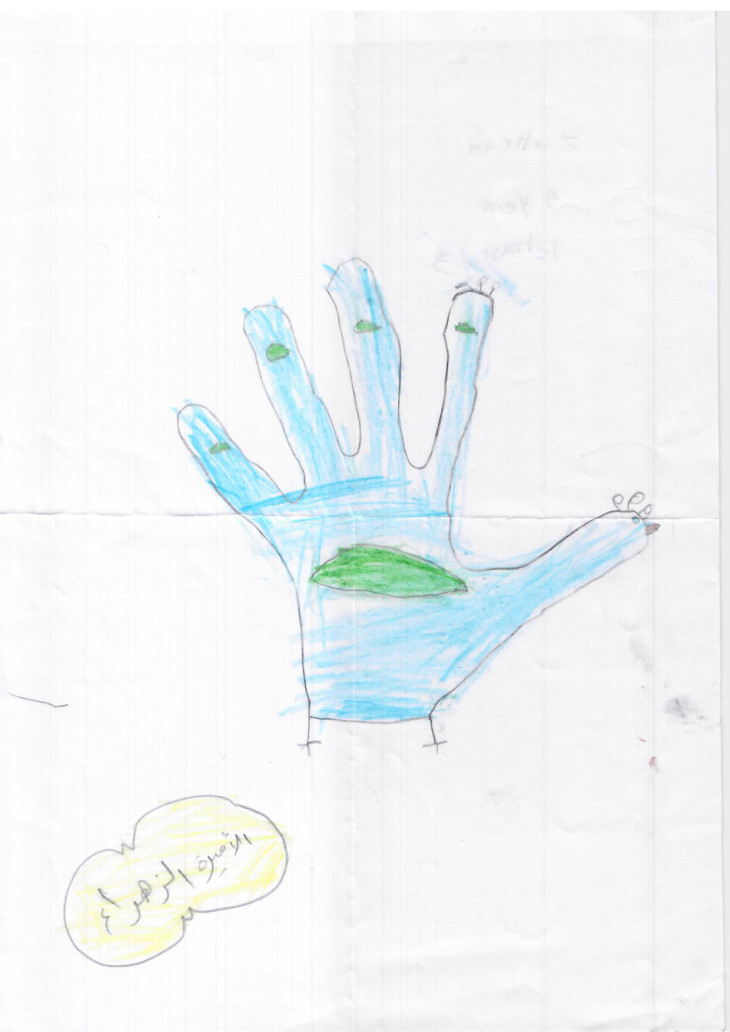

These are some of the drawings done by children in Al-Hol.

Azzam, 7

Azzam's mother is undergoing physiotherapy treatment at the hospital.

The seven-year-old has several health issues. He has a hole in his heart, problems with his kidneys and bloody urine. Medics say some issues are related to trauma.

Azzam likes to play football and to draw. He drew a flower and said that it is a gift from him to the hospital's medical staff.

Nibras, 7

Nibras came to the hospital because her leg was badly burned. While the seven-year-old's condition has improved, she still needs an operation in order to walk properly.

Nibras dreams of becoming a teacher.

Tha'er, 13

To help him overcome enuresis, Tha'er has been receiving psychosocial support.

The 13-year-old lost his father, sister and a brother during fighting. He has one remaining brother.

The violence that he has been exposed to is reflected in his drawings – he draws fighter-planes, weapons, missiles and people being burned. He wants to become a doctor.

He said: ''I wish I could become a doctor. If I was a doctor, maybe I would have been able to treat my father, brother and sister, so they would still be alive today."

Othman, 11

Othman's father was killed during fighting in Baghouz.

The 11-year-old has three brothers, one of whom was badly burned. Othman accompanied his brother to the hospital in Al-Hol for nearly one month.

Othman's dream is to leave the camp and become an engineer.

Seaf, 7

Seaf suffered from urinary incontinence. But doctors at the Al-Hol hospital could not identify any medical causes, so they recommended psychosocial support.

ICRC psychologists identified that the seven-year-old had a deep fear of military personnel and violence in the camp, which was causing his incontinence. After several psychosocial sessions, they managed to help him overcome the condition.

Seaf has two younger siblings. He wants to return to his homeland and go to school. He dreams of becoming a footballer.

Shahed, 12

Shahed lives with her mother in the camp. Her father passed away.

The 12-year-old likes to draw and wants to go home. She wants to become a teacher.

Abbas, 13

Abbas lives with his mother and four siblings in the camp.

He likes to draw animals and the emblems of the ICRC and Syrian Arab Red Crescent. Abbas wants to become a footballer.

Jafar, 8

Both Jafar and his mother are receiving psychosocial support. The pair live alone in the camp after his father died.

The eight-year-old likes to draw butterflies and flowers.

Ra'ed, 6

Ra'ed lives with his mother in the camp. The six-year-old likes to draw cars, hearts, the sun and trees.

His dream is to become a footballer.

Zahraa, 9

Zahraa is nine years old and lives with her parents and five-year-old sister.

She likes to play with dolls.

Families in Syria need you

Today your donation can make a difference for the most vulnerable.

DONATE NOW