Cholera, crowding and creative construction in Lebanon

As cases of cholera and acute watery diarrhoea grip Lebanon, supporting public infrastructure is essential to avoid devastating health and humanitarian consequences.

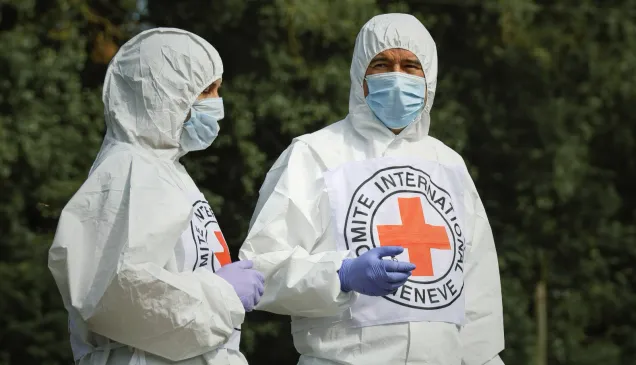

Joe Mclean, from County Mayo in the west of Ireland, works for the ICRC as a construction project manager in Lebanon.

"My role here is focused on the Tripoli Governmental Hospital in the north of the country, working to increase access to health care.

"One of the first days on this project, I walked into the hospital ER and was overwhelmed by the number of people crammed into it. Mums and dads with sick children on their lap, people sitting on the floor, there simply wasn't space for people to keep a safe distance from each other.

"It was a really visual reminder of how important this new building is going to be for patients and families.

"The goal is that patients will benefit from well-maintained emergency rooms and wards with access to quality health services."

Stepping into the humanitarian sector

It's Joe's first time in Lebanon, although his work with humanitarian organisations has taken him around the world, from Afghanistan to Zambia.

"After graduating I worked in the private sector in Ireland for a decade. Then we hit a recession. I decided to take the opportunity to go into humanitarian work; something I'd always wanted to do.

"I spent a year in Guatemala with a very small NGO, then two and a half years in Zambia. After that, I worked with MSF in southern Afghanistan. I also spent time in Sierra Leone, just at the end ofthe Ebola crisis."

"Lebanon is unlike anywhere I've ever worked before."

Lebanon is three years into an economic crisis which the World Bank describes as 'among the worst the world has seen'. Right now, the economic impacts of the war in Ukraine and a spike in cholera and cases of acute watery diarrhoea are combining to put essential public services under huge strain.

Healthcare infrastructure was also impacted by the August 4 blast (Pictured: Soeurs du Rosaire Hospital in Beirut).

"It's essential to think long-term and systemic change with our work here. We're mindful that any system that we introduce into the hospital needs to be maintained after we leave.

"That's always a crunch point, as an engineer with these kinds of projects; you can implement something that looks great on paper but then when you leave it breaks down and there's no one there to operate or upkeep. We work hard here to build on the existing capacity of the hospital maintenance teams."

An ambitious project

"The project I'm working on is to remove the existing primary health care centre - which is currently located next to the ER within the main hospital building - and relocating that across the road into a brand-new structure.

"We'll be freeing up space within the ER at the hospital and completely reimagining it, giving it a whole fresh look."

But this project is about far more than aesthetics.

"It's focused on solving the major challenges around patient flow, security and access as well as increasing the capacity of the existing ER.

"One of the main goals is rehabilitating the air conditioning ventilation system within the hospital, and the wastewater treatment system."

Hit by cholera

Since Joe arrived to work on the project, there's been one word on everyone's lips: cholera.

At the moment this wastewater treatment system is of paramount importance to the hospital because of the cholera outbreak.

"When the plumbing and wastewater treatment system isn't functioning properly that means cholera remains in the wastewater for a significant period, increasing the risk of an outbreak -- among very vulnerable patients.

"With the economic crisis and the strain on public infrastructure, the piping systems and treatment plants across Lebanon are severely limited. If wastewater comes from hospital, it enters the main system, and the system can't adequately treat it."

Very disappointed that the unprecedented #cholera outbreaks hitting 29 countries are not getting the needed attention.

In #Syria & #Lebanon, both enduring so much, the situation is critical. In addition to emergency support, @ICRC works to improve access to clean water. https://t.co/XcHerdSk32— Fabrizio Carboni (@FCarboniICRC) November 17, 2022

A lurking catastrophe

"Especially during the rainy season, we're talking about wastewater coming up through the manholes bubbling up onto the streets.

"Obviously that's never a good situation, but when that water is potentially infected with cholera bacteria, it can be truly catastrophic to a population.

"So that's one of my key projects, looking at treating the wastewater from the hospital by heavily chlorinating it. That's a temporary measure, but we're also looking at the whole hospital's long-term needs."

All communities are affected

Lebanon hosts an estimated 1.5 million Syrian refugees and almost half a million registered Palestinian refugees. The acute financial and economic crises have an impact on all communities in Lebanon.

These people are never far from Joe's mind.

"My work here involves a lot of back and forth between the different stakeholders. I don't find that process frustrating, I enjoy getting down to the nitty gritty of how this is all going to work. Because I know how important it is to get the best product possible for the end users."

"I always remember the people, which in this case of course are the patients. The local families, as well as Syrian and Palestinian refugees who also use the hospital."

Building for people

Patient flow is crucial to Joe's construction project.

"Tripoli Governmental Hospital is an extremely busy hospital and there are issues with patient flow within the existing emergency department.

"People are having difficulty accessing the ER, and things are made more difficult because people often arrive with multiple family members.

"It's also relatively common for family members to attend the ER with weapons, warning staff to take care of their loved one. For the ICRC this is a really serious issue, and we work to reduce this as part of our healthcare in danger programme.

"Then if you remember the rise in cholera that the health care teams are seeing here, that also plays into patient flow."

Mapping out the problem

"There's a special cholera treatment centre within the hospital grounds, where patients are given oral rehydration, intravenous fluids, and then, if needed, they're transferred to the main hospital, to intensive care.

"So, you can start to map that out – patients are coming in, being diagnosed, being treated, and then potentially moved again if their treatment is being escalated.

"It's all about infection prevention and control, the treatment of wastewater, and the provision of clean water to prevent infection of other patients.

"This all factors into our designs for the construction of the new building as well as the refurbishment of the ER. How can the building plans support best-practice care for patients? How can we increase access, maintain security, and reduce infection spread?

"I'm in constant contact with the ICRC health team, the management in the hospital and the Ministry of Public Health to develop these designs to make sure that all the stakeholders are happy with them before we proceed to the next stage."

Hard to say goodbye

Joe is finishing up his current role, but he won't forget his experiences in Lebanon.

"I have felt so welcomed by the Lebanese people in general. Everyone has been so warm and extremely patient as well! Arabic is the main language here, which I unfortunately don't speak. I've never had one person getting frustrated or annoyed that I couldn't speak the language, people are so keen to translate and support.

"For the most part the people here love their country and their culture. That feeling of comradery and connection seems very much like Ireland in some ways. I've really felt at home."

In Lebanon, the ICRC is helping with:

• Rehabilitation or emergency operation of water supply and treatment systems in the most-affected areas, including emergency fuel supply.

• Support to water utilities with provision of items required for water testing countrywide.

• Supporting the Lebanese Red Cross response, including water purification tablets and hygiene kits for 2,700 households.

• In both Rafiq Hariri University Hospital and Tripoli Governmental Hospital, providing support to establish standard procedures on infection control, waste management, patient flows and protocols for cases management. ICRC will deliver one cholera kit to each of the two hospitals including infusion treatment, IV treatment, plastic sheeting, pulverization insecticide, and chlorine, enough to treat. Each kit is enough to treat 500 cholera patients.

• Support to detaining authorities including rehabilitation of the water supply system in Roumieh Central Prison, serving about 4,000 detainees; and coordination to support LRC's cholera vaccination in places of detention.

This piece was published by the ICRC team in the UK and Ireland. Find out more about our work and follow us on Twitter.